Yates Row: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

A classic back exercise named after the legendary Dorian Yates, the Yates row is essentially a conventional barbell row performed with the hands in a supinated orientation. This requires a somewhat more upright torso angle, and shifts more emphasis towards the muscles of the upper back.

But before including this mass-building back exercise into your workout, it’s important to understand the specific situations in which it is most useful.

Throughout this article, we will discuss just that - as well as the benefits of the Yates row, what specific muscles receive the most benefit and a few common mistakes you’re better off avoiding.

What is the Yates Row?

In technical terms, the Yates row is an open chain compound movement meant to be performed with free weights for moderate volume sets.

The Yates row primarily involves elbow flexion, scapular retraction and hinging at the waist in order to target the muscles of the middle and upper back.

In comparison to its closest counterpart (conventional barbell rows), the Yates row has two main distinctions - that being an underhand grip and a slightly more upright angle to the torso. These changes in stance create greater emphasis on the elbow flexors and upper back muscles while simultaneously reducing strain on the lower back and spine.

Is the Yates Row Right for You?

Although the Yates row is somewhat safer than other row variations in certain aspects, it still requires basic understanding of proper row mechanics.

As such, the Yates row may be considered an intermediate-level exercise that is best performed once a solid grasp of spinal neutrality and proper muscular contraction is present.

The Yates row is most effective when used as a method of building upper back mass in bodybuilders and other types of lifters who do not wish to maximize weight lifted with each repetition.

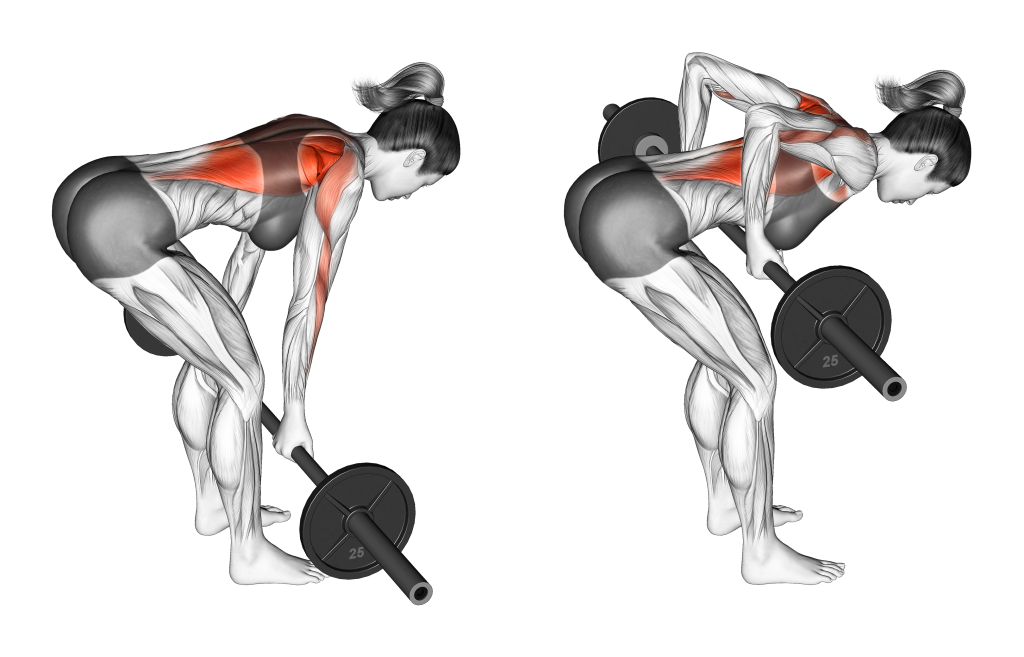

How to do the Yates Row

In order to perform a repetition of the Yates row, the lifter will first begin by standing upright while holding a loaded barbell at arms-length. The knees should be slightly bent and the torso hinged forwards at a 45 degree angle with the hips pushed slightly back.

Furthermore, the hands should be set around shoulder-width apart along the bar in a supinated grip. The core should be braced and the neck aligned with the rest of the spine, lower back flat and neutral.

Now in the correct stance, the lifter will contract their back muscles and pull the barbell towards the base of their ribcage, bending the elbows and retracting their scapula as they do so.

Avoid utilizing the biceps as much as possible, instead relying on the lats and other back muscles to pull the barbell backwards.

Once the barbell is touching the sternum or abdomen, the lifter then slowly releases the tension in their back and lengthens their arms until the bar has returned to its original position. This marks the completion of the repetition.

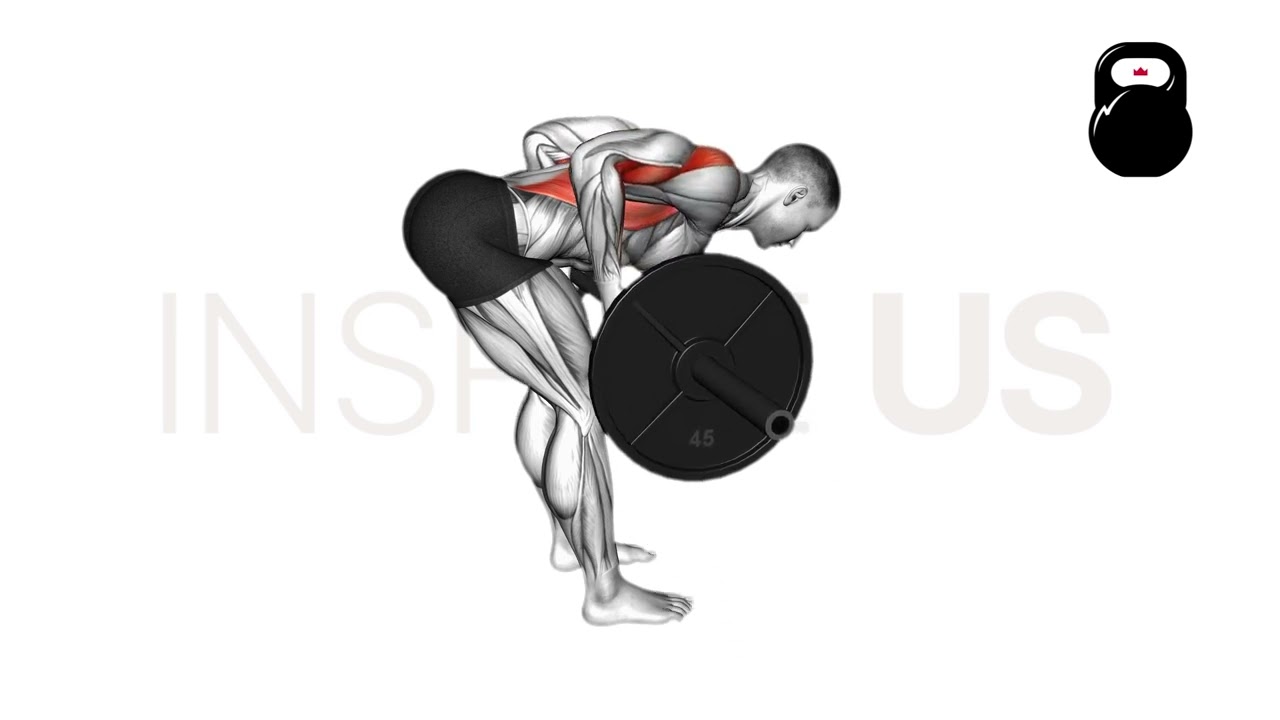

What Muscles are Worked by the Yates Row?

The Yates row is a compound exercise, meaning multiple muscles are contracted in both a static and dynamic manner.

These help stabilize joints as they move through the exercise or otherwise directly contribute to the movement of such joints. For static contraction, the muscles are referred to as “stabilizers” - and for dynamic contraction, “movers”.

Mover Muscles

The Yates row primarily targets the latissimus dorsi, lower trapezius, rhomboids, teres major and minor and the biceps brachii.

Each of these muscles is contracted in a dynamic manner during certain portions of the Yates row - allowing them to undergo muscular hypertrophy and strength adaptations. This is particularly true for the muscles of the mid-back (lats, rotator cuff muscles) as they exert the majority of the force needed to row the bar.

Stabilizer Muscles

Apart from the mover muscles, the core musculature, erector spinae, posterior deltoid head, brachialis and brachioradialis are also used to help keep the body stable and the stance tight throughout the Yates row.

Unlike the mover muscles, the stabilizers do not visibly lengthen or shorten during contraction. This reduces the likelihood of muscular hypertrophy occurring and means that the stabilizer muscles do not contribute as much force into the movement.

What are the Benefits of Doing Yates Rows?

Yates rows are often picked over other row variations due to their benefits - the majority of which have to do with greater muscular development and a lower risk of injury.

Excellent for Building Upper Back Mass and Strength

The defining benefit of the Yates row is its capacity to develop mass and strength in the muscles of the upper back. The muscles that benefit the most from this are the rhomboids, teres muscles, lower trapezius and the lats.

Because the Yates row involves an approximate shoulder-width grip with the torso at a 45 degree angle, these muscles are emphasized to a greater degree than would be the case with closer grip row variations that set the torso parallel to the floor.

Of course, this is also affected by the manner in which the Yates row itself is programmed. Moderate volume and moderate weight will allow for both hypertrophy and strength to be developed equally.

Target the Biceps to a Comparatively Greater Degree

Although nearly all other row variations do indeed recruit the biceps, it is rarely to the degree that the Yates row does.

This is simply because other horizontal pulling exercises are performed with the wrists in a neutral or pronated orientation, meaning that the biceps are less able to exert force when performing them.

In addition, the Yates row places the barbell lower along the body than is seen with row exercises that feature a more horizontal torso orientation, further aiding in the recruitment of the biceps.

Less Likely to Result in Shoulder Injury

Because the Yates row is less likely to involve flaring of the elbows, the humerus is at a less impactful angle within the entire shoulder joint structure. This reduces irritation of soft tissues within the joint and greatly reduces the risk of impingement or dislocation.

In order to ensure that no shoulder injuries occur, it is important for lifters to be mindful of their elbow angle as they row the bar. Aim to draw the elbows behind the body, rather than out to the sides.

Carryover to Other Horizontal Pull Exercises

Even outside of strictly barbell row exercises, performing the Yates row can indirectly improve execution of most other horizontal pulling movements. Exercises like the inverted row or front lever can both be made easier and safer by first mastering the Yates row beforehand.

This is done by both familiarizing the lifter with relevant mechanics like scapular retraction and elbow flexion, as well as strengthening muscles that are also used in such movements.

Less Strain on the Spine and Back

In comparison to exercises like the Pendlay row or conventional barbell row, the Yates row is considerably less strenuous on the muscles of the lower back.

Furthermore, a significantly lower risk of spinal injury is also a benefit of Yates rows - both of which are a result of the less horizontal torso angle present.

Remember to first consult a medical professional prior to performing Yates rows if you have a history of lower back injuries.

Allows for Greater Load Capacity

With a greater torso incline and the bicep being involved to a higher degree, the Yates row will allow lifters to load more weight than they would otherwise be able to with exercises like the T-bar row or conventional row.

Although it isn’t quite advisable to perform the Yates row as a high-resistance low-volume exercise - this greater loading capacity can be used to help condition strength athletes to carrying significant amounts of weight or otherwise create a greater emphasis on strength-building.

Common Yates Row Mistakes

In order to get the most out of the Yates row and avoid any injury, avoid the following common mistakes.

Insufficient Range of Motion

One of the most frequently encountered errors seen when lifters perform the Yates row involves a short range of motion. Be it failing to pull the bar fully towards the torso or not extending the arms far enough down, either case will affect how well the muscles are targeted by the Yates row.

Rounding the Upper or Lower Back

As is the case with most other exercises, rounding the back while performing a Yates row will lead to strain of the spine and the muscles that protect it. Rounding the lower back is especially a problem as it will negate much of the safety benefits inherent to the Yates row itself.

In order to avoid this particular mistake, ensure the core is fully braced, attention is paid to spinal curvature and the scapula does not protract throughout the exercise.

Overly-Involving the Biceps

Although some level of biceps brachii involvement is needed to create elbow flexion, avoid curling the barbell upwards as this may lead to biceps strains and tears.

Rather than initiating the pull through the arms, it is best to first pull through the muscles of the back with the biceps acting in a supportive capacity instead.

Internal Shoulder Rotation

Just as how the shoulder blades should not protract to an excessive degree when performing the Yates row, the deltoids should also remain in a neutral or externally rotated state during the repetition.

Allowing them to internally rotate may be a sign that too much weight is being lifted, or that the lifter is failing to properly engage their upper back muscles.

Excessive/Insufficient Torso Bend

One of the defining characteristics of the Yates row is its greater torso incline in comparison to other row variations. This is often described as being around a 45-degree angle.

However, performing the exercise at a different torso angle can cause the biceps to be at a greater risk of tears, as well as place greater strain on the lower back as the exercise is performed.

Because it is not advisable to turn the head when performing the Yates row at full weight, it is best to practice achieving the correct torso angle with an empty bar in front of a mirror.

Using the Legs for Momentum

The Yates row is a back and biceps exercise, not a lower body one. The legs should play no role other than a supportive one when the Yates row is being performed.

While the knees should indeed be slightly bent so as to aid with blood flow and mobility, avoid voluntarily generating momentum with the muscles of the legs. This will negate much of the benefits derived from the Yates row, and otherwise lead to a greater risk of injury.

If you are having trouble performing the Yates row without utilizing your legs, it is possible that you are either attempting to lift too much weight or have issues with lower back mobility.

Alternatives to the Yates Row

If the Yates row isn’t quite what you need out of your training program, try the following alternatives out.

Pendlay Rows

The Pendlay row can be considered the opposite of the Yates row as far as rows are concerned.

Rather than an underhand grip and an upward tilt to the torso, the Pendlay row is performed with the upper body directly parallel to the floor, biceps largely eliminated from the recruitment pattern. This creates far greater emphasis on the back muscles and maximizes the possible range of motion involved.

Pendlay rows are the ideal alternative if you find the Yates row to be too biceps-focused and short for your liking.

Conventional Barbell Rows

Of course, it is entirely possible to return to basics and swap out the Yates row for the conventional bent-over barbell row. This will reduce the risk of biceps injury and shift more focus towards the middle and lower back muscles.

Chin-Ups

Although a vertical pulling exercise rather than a horizontal one, chin-ups target much the same muscles as the Yates row to a similar intensity per muscle.

Alternating with chin-ups can allow lifters to still work their biceps and upper back without the need for weightlifting equipment or an increased risk of lower back strain.

Naturally, depending on your weight and experience level, it is possible that chin-ups will not be as challenging as the Yates row. To combat this, performing the exercise with additional weight may be needed.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the Difference Between the Yates Row and the Regular Row?

The Yates row primarily features an underhand grip and a greater incline to the torso. This shifts more emphasis towards the upper back and the biceps, rather than the mid-back and lower back as is the case with conventional rows.

Why is it Called the Yates Row?

The Yates row is named as such after legendary bodybuilder Dorian Yates, who was known for having a highly developed upper back - among other parts of his body.

Is the Yates Row Overhand or Underhand?

The Yates row traditionally uses an underhand or supinated grip. This means that the palms are facing upwards, allowing the biceps to be contracted to a greater degree and shortening the movement’s range.

Final Thoughts

The Yates row is an undeniably effective variant of row - so long as it is used within the right context. If your biceps or upper back muscles are lagging behind, try switching over to the Yates row.

However, keep in mind that the Yates row isn’t the only row out there. See our article on the various forms of horizontal pull if it doesn’t meet your training needs.

Remember to avoid the Yates row and similar exercises if you have a history of biceps, shoulder or spinal injuries, as such exercises can cause further injury to occur.

References

1. Lehman GJ, Buchan DD, Lundy A, Myers N, Nalborczyk A. Variations in muscle activation levels during traditional latissimus dorsi weight training exercises: An experimental study. Dyn Med. 2004 Jun 30;3(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1476-5918-3-4. PMID: 15228624; PMCID: PMC449729.

2. Murphy, Myatt. Men's Health Push, Pull, Swing: The Fat-Torching, Muscle-Building Dumbbell, Kettlebell & Sandbag Program. United States: Rodale, 2014. ISBN: 9781623363987, 1623363985