Weighted Push Up: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

When conventional push-ups are no longer challenging enough to elicit a response from the muscles, exercisers are given the choice of progressing to more complex alternatives, or to double down on the push-up by adding more resistance.

This has led to the development of the weighted push-up; a conventional push-up with weight added in addition to that of the body, allowing intermediate and advanced exercisers to continue the flow of their progression.

Weighted push-ups are simply regular push-ups with weight added in the form of weight plate carriers, wearable fitness equipment or through the use of somewhat more unconventional means, like a backpack or resistance band.

What is the Weighted Push-Up?

The weighted push-up is a free weight multi-joint compound exercise frequently used as the primary compound movement in upper body workout sessions.

Like the regular push-up, weighted push-ups are preferred by calisthenic athletes or at-home exercisers, as it allows for a more convenient and versatile workout to be created.

While most weighted push-ups are performed in the same manner and with the same goals in mind, they differ in terms of how the weight is placed on the lifter’s body, as well as the angle of resistance created by this placement of weight.

Who Should Do Weighted Push-Ups?

Weighted push-ups are more appropriate for exercisers at the intermediate or advanced stages of training, as it is meant to act as a progression from regular push-ups and may be too difficult for individuals who are new to resistance training.

In particular, calisthenic athletes will find the weighted push-up to be the most appropriate choice of upper body pushing exercise - especially in comparison to movements like the bench press - on account of the push-up’s more functional training stimulus.

Equipment Needed for Weighted Push-Ups

The sort of equipment used (and its placement) is where most weighted push-ups will differ, and as such can play a large part in the effectiveness and safety of the exercise.

The majority of calisthenic athletes will make use of wearable weights like weighted vests or equipment that allow weight plates to be attached to the torso - though exercisers on a budget may wish to simply place several weight plates in a tightly secured backpack instead.

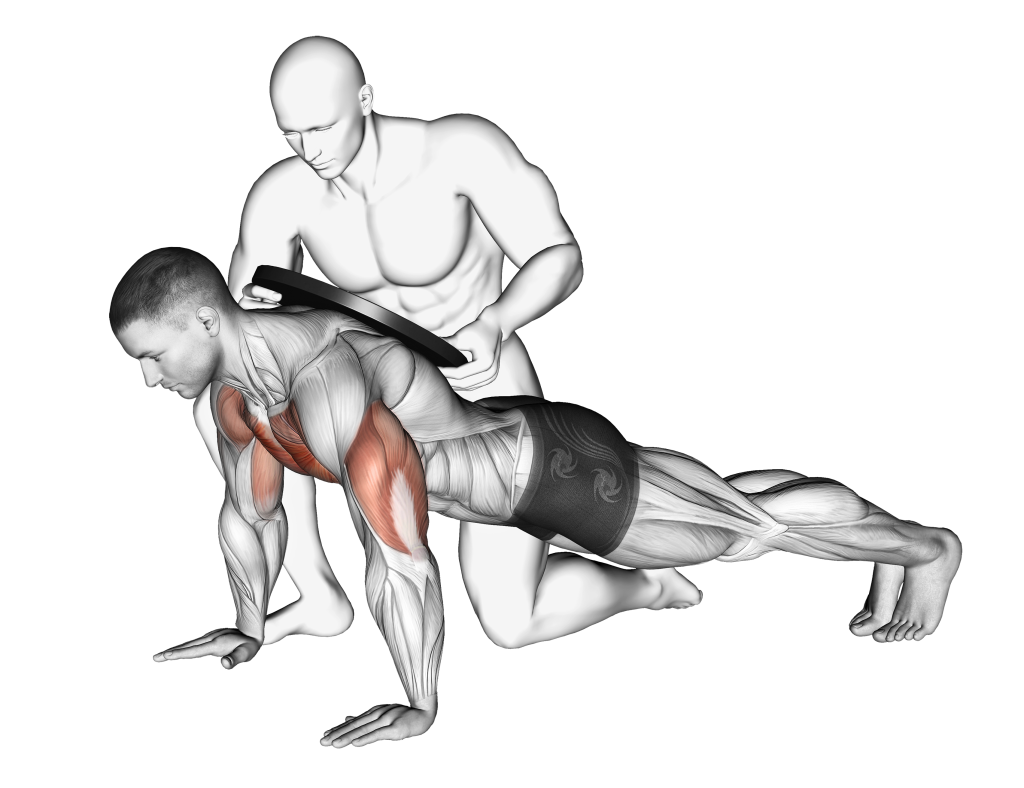

Finally, if all other avenues are unavailable, it is possible for the lifter to have a friend place a single weight plate atop their back. So long as they are confident that they can maintain their balance, the lifter should be able to safely perform weighted push-ups in this manner.

How to do Weighted Push-Ups

Performing weighted push-ups is no different from performing regular push-ups.

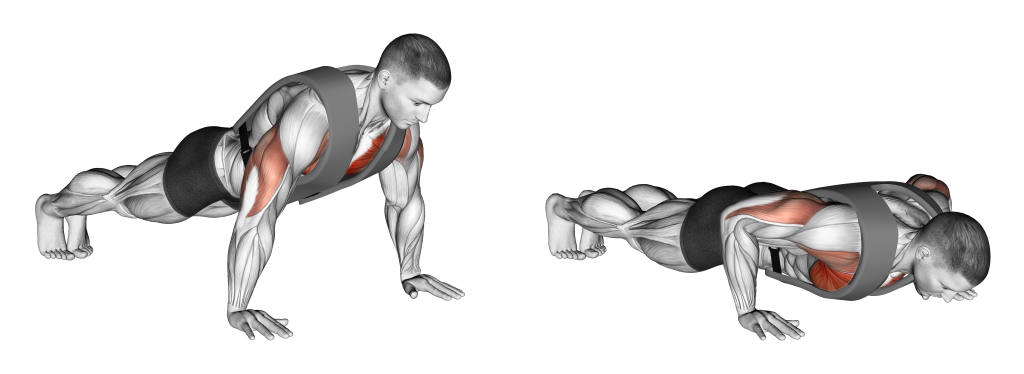

To begin, the lifter will enter a plank position with their core firmly contracted and their hands set parallel to the shoulders, spaced wider than shoulder-width apart.

Bending at the elbows, the lifter will then lower their chest until it is within several inches of touching the floor, squeezing the triceps, deltoids and pectoral muscles as they reach the bottom of the repetition.

From this position, they will then push through their palms, extending their elbows and effectively returning to the starting plank position - thereby having completed the repetition.

What Muscles are Worked by Weighted Push-Ups?

Weighted push-ups are a compound exercise, and as such will work more than just a single muscle group at a time.

Such muscles trained by the weighted push-up are differentiated by the role they play within the push-up’s movement pattern, with those worked to the greatest degree being called “primary mover” muscles, and other muscles worked to a lesser or static capacity being called “secondary mover” muscles.

Primary Mover Muscles

The main muscles used by the weighted push-up are the pectoral muscles, the anterior deltoid head and the triceps brachii.

Each muscle contributes a significant amount of force to the movement pattern of the weighted push-up, and receives significant development from regular performance of the exercise.

If you do not “feel” the exercise in any of these muscles, it is possible that the weighted push-up is being performed with poor form.

Secondary Mover Muscles and Stabilizing Muscles

Other muscles that are recruited to a lesser extent by the weighted push-up are; the serratus anterior, the muscles of the core and the remaining two heads of the deltoid muscles.

These muscle groups act in a manner that helps stabilize the body as it moves through the push-up’s range of motion, as well as aid the primary mover muscles in force output.

What are the Benefits of Doing Weighted Push-Ups?

Apart from the usual benefits of performing resistance exercise, weighted push-ups can also allow lifters to achieve certain benefits that wouldn’t be possible with other exercises.

The majority of said benefits have to do with the functionality and training stimulus provided by the weighted push-up, and are invaluable for any athlete or individual seeking a more functionally-sound physique.

Excellent for Building Chest, Shoulder, and Tricep Mass

Just as is the case with other heavy push exercises, the weighted push-up is excellent for building muscle mass in the triceps, pecs and deltoids - so much so that it can even rival exercises like the bench press or dips.

So long as the weighted push-up is programmed with a conducive amount of volume and backed up by proper recovery, there is no doubt that significant muscular hypertrophy will occur in the chest, arms and shoulders.

To maximize muscle mass developed from weighted push-ups, performing 3-4 sets of 5-10 repetitions each is ideal.

Effective as a Core Strengthener

Because the conventional push-up is already considered to be excellent for strengthening the core (on account of the plank position being used), it should be no surprise that adding further resistance through the weighted push-up will further improve upon such benefits.

Not only will weighted push-ups improve the endurance and strength of the core muscles, but they will also help target a core-adjacent muscle (the serratus anterior) that is vital for many actions involving scapular extension.

Perfect for Athletes and Athletic Training Programs

The weighted push-up provides a more athletically-inclined training stimulus than other push exercises, allowing it to be used in lieu of movements like the bench press or chest fly for athletic training programs.

This is a benefit derived from its more explosive nature and the fact that it presents better carryover potential to real-world activities than other chest-focused compound exercises.

For the best results, using a low amount of weight alongside training strategies like supersets, ramping volume or more dynamic push-up variations will maximize the athletic benefits derived from the weighted push-up.

Develops Upper-Body Power and Explosiveness

While all resistance exercises build muscular explosiveness and power to a certain extent, the weighted push-up excels in these categories on account of its relatively short range of motion, angle of resistance and comparatively unique form.

As such, lifters seeking greater power and explosiveness in their upper body may wish to substitute some of their push-day volume with the weighted push-up, if not switch over their primary compound movement entirely.

Relatively Safer than Other Chest Exercises

Though the majority of chest exercises are safe when performed with the correct form, the weighted push-up is particularly so due to the fact that it is easy to “bail” out of the repetition when complete muscular fatigue occurs.

Unlike with the bench press or chest fly, the lifter need simply lower their torso to the floor if they find that they cannot complete a repetition - a far cry from potentially becoming pinned beneath a barbell or dropping dumbbells onto oneself, as is the case with other exercises.

Furthermore, weighted push-ups involve the weight being intimately in-contact with the exerciser’s own body, reducing impact on the joints of the body and helping to prevent the limbs from being pulled into a disadvantageous position.

That being said, it is important to keep in mind that performing the weighted push-up improperly or with sub-optimal equipment can just as easily injure the lifter; Following proper form and setting-up the exercise properly are absolutely vital.

Most Common Mistakes of the Weighted Push-Up

Though there are quite a number of form errors that one can make with any push-up variation, there are a few mistakes that are particularly common with the weighted version of the exercise - all of which should be corrected as soon as possible, in case they result in injury to the lifter.

Loading the Weights on the Wrong Part of the Back

Perhaps the most frequently encountered error of the weighted push-up has to do with where the weight is placed atop the exerciser’s back.

While the majority of weight vests involve placing the weights immediately between the shoulderblades, lifters may improperly adjust their equipment or - if they do not have access to wearable weights - place weight plates on the wrong part of the back, reducing the effectiveness of the resistance or even jeopardizing the safety brought by their push-up stance.

Placing the weights off to one side of the body will cause one arm to bear more resistance than the other, leading to premature muscular fatigue and a greater risk of developing muscular imbalances.

Likewise, setting the plates too low on the back (such as beneath the rib cage) will cause less of the weight to be lifted by the upper body, instead shifting it towards the legs and core and thereby reducing the effectiveness of the exercise.

For the best results, the weight should sit comfortably atop the upper back (pictured above), preferably secured by a vest, set of straps or a backpack in such a way that the weight does not shift and injure the lifter as they go through the movement pattern of a push-up.

Setting the Hands Too Close Together

As is the case in all push-up variations, beginning a set with an improper stance can easily lead to injuries of the elbows, wrists and shoulders. This is especially important with the weighted push-up, as the increase in weight (and therefore pressure) also causes an increase in injury risk.

When performing conventional weighted push-ups, the hands should be set wider than shoulder-width apart at the least, even if a more narrow stance feels more stable to the lifter.

Setting the hands a sufficient distance apart reduces the vertical pressure placed on the elbows and wrists, and ensures that the shoulders may rotate externally, rather than internally, which may result in impingement and strain.

Using Multiple Unsecured Weight Plates

For lifters performing the exercise without some sort of secured training equipment (i.e. a vest, belt or backpack), using multiple weight plates stacked atop their back can easily result in injury, as the plates may slip atop each other, potentially landing on the hands or striking the back of the head.

If the lifter has developed enough strength to exceed the viability of a single weight plate, the safest option is to invest in wearable calisthenic equipment - if not to perform more complex variations of the weighted push-up instead.

Are There Variations of the Weighted Push-Up?

As solid as the weighted push-up is, more advanced athletes may require greater specificity in their workout - or even a relatively lower level of intensity.

Regardless of what aspect of the weighted push-up one may wish to accentuate, there is doubtless a potential variation for their needs.

1. Weighted Deficit Push-Ups

For exercisers that wish to elicit greater pectoral muscle recruitment, the weighted deficit push-up is the perfect variation. It is defined by a greater range of motion on account of the hands being elevated higher off the ground, allowing for a longer time under tension and greater results as a whole.

2. Weighted Incline and Decline Push-Ups

Both the weighted incline and decline variations of the push-up are exactly as they sound; conventional push-ups performed with the torso at an angle to the ground, altering the focus of the exercise.

The decline variation of the push-up is considered to be more difficult due to more of the weight being placed on the upper body, and will increase emphasis on the anterior deltoid and pectoralis minor muscles.

Conversely, the incline variation is considered to be easier, and features greater lower pectoral muscle recruitment at the cost of a shorter range of motion.

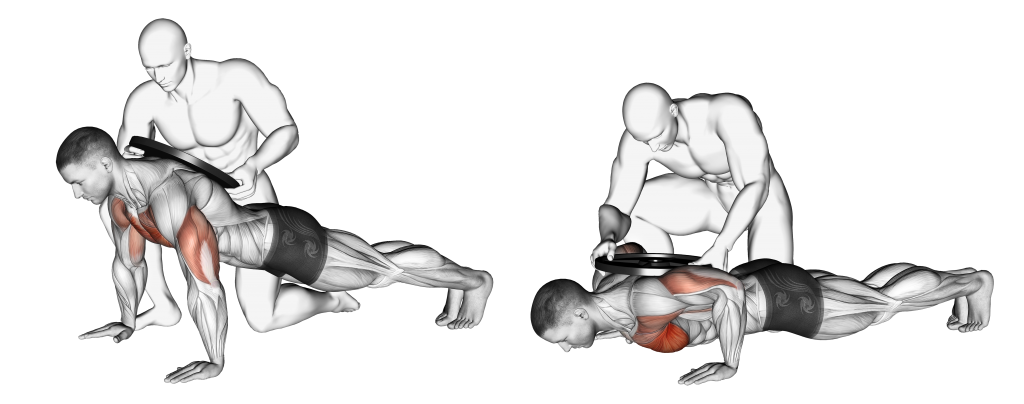

3. Weighted Knee-Ups

For exercisers that find they cannot maintain proper core contraction (or those that wish to perform back-off sets), the weighted knee-up is a perfectly viable alternative to the weighted push-up.

Unlike weighted push-ups, weighted knee-ups are performed in a semi-kneeling position, rather than a plank position. This largely eliminates involvement of the abdominal musculature, and reduces the intensity of the exercise as less of the lifter’s weight is moved by their upper body.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Are Weighted Push-Ups Effective?

Yes - weighted push-ups are very effective, especially at building up mass and strength in upper body muscles like the pectorals, deltoids and triceps.

For the best results from weighted push-ups, proper form must be used, and sufficient rest and caloric intake should be maintained as much as possible.

How Much Weight Should You Use for Weighted Push-Ups?

When performing weighted push-ups, the right amount of weight to use is one that allows you to perform 8-12 repetitions without reaching a state of complete muscular failure - or what is known as “keeping one in the tank”, so to speak.

It is better to err on the side of using too little weight, rather than too much, as overloading the body with weighted push-ups may result in injury and can lead to a failure in form adherence.

Can I Do Weighted Push-Ups Every Day?

No - it is a bad idea to perform regular push-ups on a daily basis, let alone weighted push-ups.

In order to ensure no overtraining or injury occurs, it is best to perform weighted push-ups up to three times a week at maximum, with rest days interspersed between workouts targeting the same muscle groups.

This is done to allow for the body to recover.

In Conclusion

If you’re new to performing weighted push-ups, make sure to properly warm-up with a set of regular push-ups before beginning with the weighted variation.

Furthermore, if you’re unsure of how much weight to start with, try the lowest possible denomination of weight plate available in your gym before working your way upwards.

References

1. Vaseghi B, Jaberzadeh S, Kalantari KK, Naimi SS. The impact of load and base of support on electromyographic onset in the shoulder muscle during push-up exercises. J Body Mov Ther. 2013;17:192–199.

2. Hinshaw TJ, Da B, Stephenson ML, Sha Z. Effect of external loading on force and power production during plyometric push-ups. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32:1099–1108.