Wall Crunch: Muscles Worked and More

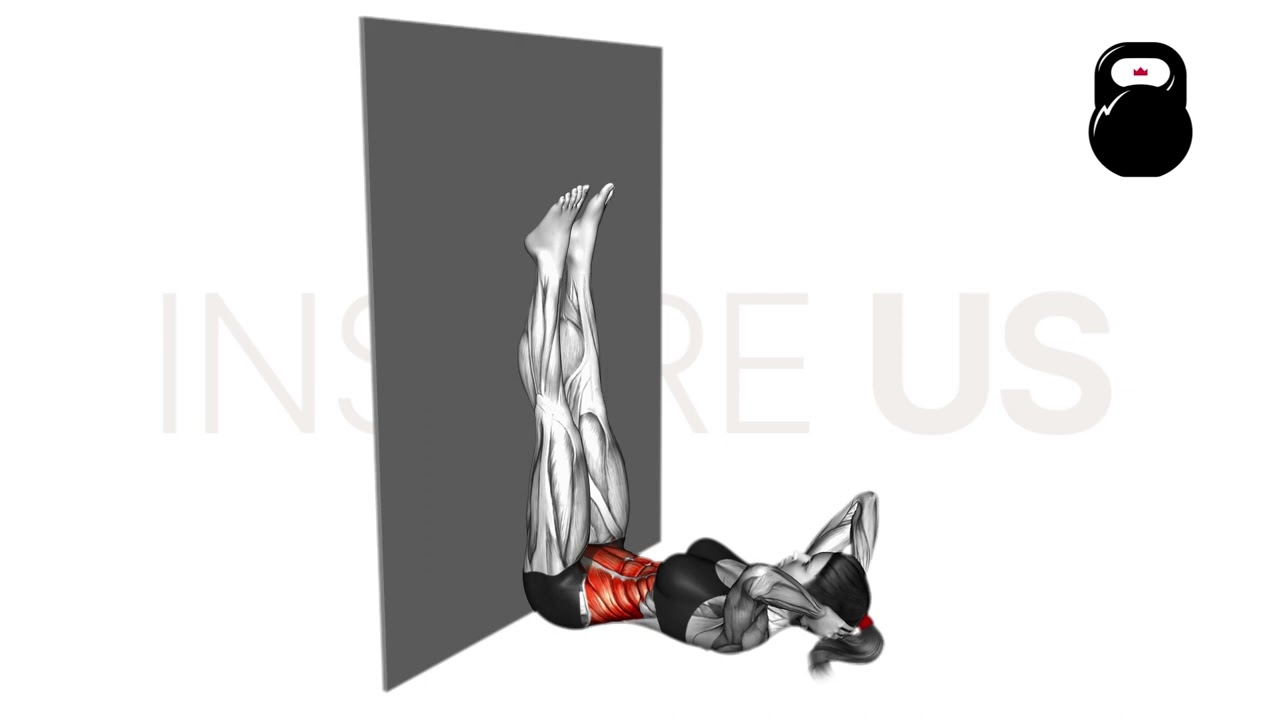

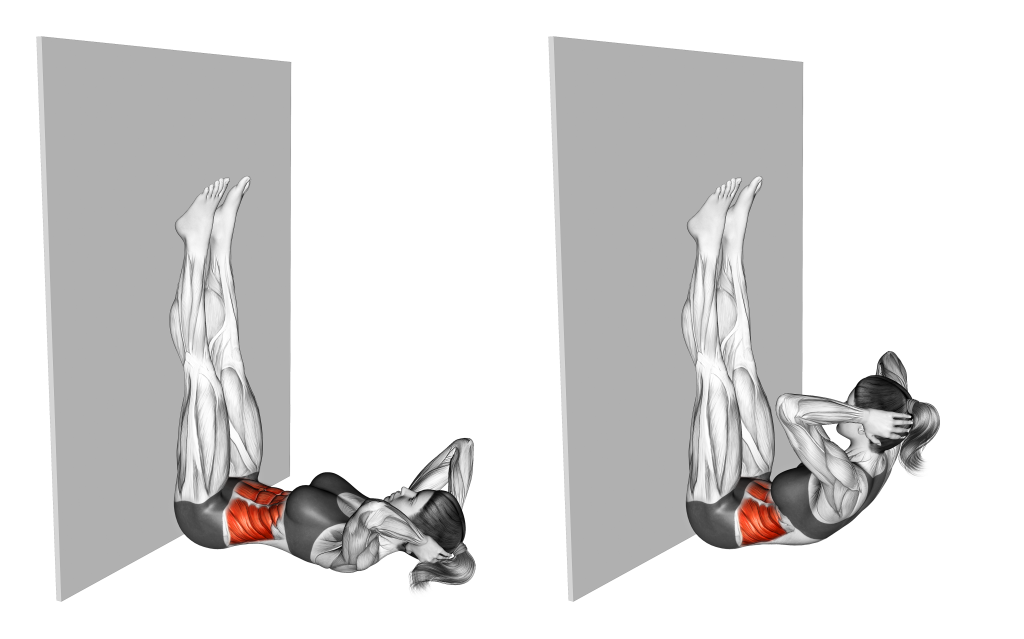

Wall crunches involve the exerciser placing their legs straight up against a wall as they flex the trunk at the waist using their core musculature.

It is most frequently employed as an exercise meant for improving abdominal muscle function - especially for those who find conventional crunches to be too easy or too unstable.

What are Wall Crunches?

The wall crunch is a bodyweight isolation exercise primarily relying on trunk flexion at the abdomen to complete its movement pattern.

Because wall crunches are quite hard to load with additional weight, they are primarily kept as a calisthenics exercise performed for high volume sets.

Regardless of whether included into a bodyweight or weighted training program, their small scope of recruitment cements them solely as an accessory exercise when programmed.

The wall crunch is not only more intense and demands greater recruitment of the abdominal muscles, but will also help ensure proper lower body positioning - an issue seen in conventional crunches, where failing to lock the feet in place can cause them to rise off the floor.

How to Do a Wall Crunch

In order to perform a repetition of the wall crunch, the exerciser will begin by first lying on their back with their legs raised vertically up along a wall, knees extended and glutes as close as possible to the wall itself.

For maximum abdominal contraction, the exerciser should visualize “pulling their navel” towards their stomach, consciously engaging the core fully.

Supporting the base of the head with the hands, the exerciser then squeezes their core and raises their upper back off the ground, stopping just shy of raising the lower back upwards as well.

Once the abdominal muscles are fully contracted, the exerciser then slowly returns their upper back to the ground - thereby completing the repetition.

Remember that the legs must remain stationary throughout the entire set. If they begin to bend towards the upper body, try seating the glutes further away from the wall.

Sets and Reps Recommendation:

Wall crunches are difficult to load with additional weight, meaning that performers must rely on volume and tension to challenge their core muscles.

1-2 sets of 10-20 repetitions with a final AMRAP (as many reps as possible) set should work the core intensely.

What Muscles are Worked by Wall Crunches?

Wall crunches are what is known as an “isolation” exercise - essentially meaning that only a single muscle group is intended to be targeted when the movement is performed.

Of course, like all other forms of crunch, this muscle group is that of the core - encompassing both sides of the lower section of the trunk.

To be more specific, it is the anterior core musculature of the rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis and (in part) the obliques that are targeted by wall crunches.

The remaining core muscles along the posterior section of the trunk are otherwise not contracted to a significant dynamic capacity.

Common Wall Crunch Mistakes to Look Out For

Though it is indeed true that wall crunches are far stricter in stance and harder to perform incorrectly, the following mistakes are still a common occurrence.

To ensure you aren’t wasting your time and no injuries occur, correct these errors if present in your workout.

Raising Lower Back Off the Floor

The hallmark difference between a crunch and a sit-up is that the crunch does not actually require sitting up on the glutes. For the most part, the lower back never actually leaves the floor and it is solely the upper section of the back and shoulders that is raised.

Not only does this distinction mean that crunches are less likely to injure the lower back, but it also aids in properly isolating the abdominal muscles - avoiding unnecessary contraction of muscles like the hip flexors or lower back muscles.

In order to ensure that the wall crunch is as effective and safe as possible, the lower back should never leave the floor. If you find that the lower back begins to raise near the top of the repetition, it is likely that you are raising your torso too high off the ground.

Curving Upper Back

Though trunk flexion does indeed involve a somewhat forward curvature to the upper body, it is important to keep the upper back on a relatively flat plane to the middle and lower back.

Rounding the shoulders internally, hunching them, jutting the neck or simply just curving the upper back too far forwards will lead to increased strain along the thoracic and cervical sections of the spine.

Aim to keep the scapula partially retracted and the shoulders parallel with the neck while performing wall crunches.

Legs Raising Away From the Wall

In cases where the wall crunch is being performed with poor hip and hamstring mobility - or a poor stance - the legs may begin to rise away from the wall, often with the knees bending as if attempting to squat off the wall.

Performing wall crunches with overly bent knees or legs that are detached from the wall can negate many of their inherent benefits, increasing risk of injury, destabilizing the body and reducing core contraction.

An ideal wall crunch set will have the legs straightened with the heels (and possibly the calves) resting against the wall. This, of course, will depend on the performer’s posterior chain flexibility and current level of core strength. It is perfectly fine to perform the exercise with the glutes further away from the wall, legs straight but angled somewhat.

Setting Glutes Too Close to the Wall

In connection with the previous entry; performing the wall crunch with the glutes closer to the wall than your flexibility allows can cause a breakdown in your overall stance.

Aim to perform wall crunches with the glutes as close as possible to the wall without feeling a significant stretch in your hamstrings, hips or lower back.

Poorly Controlled Eccentric/Dropping to the Floor

In order to maximize the intensity of crunches, the eccentric phase of the movement should be done in a slow and controlled manner.

Despite the relatively small range of motion involved, exercisers performing wall crunches should aim to lengthen their descent back towards the floor for up to two seconds - therein ensuring maximum abdominal training stimulus.

Wall Crunch Variations and Alternatives

If the wall crunch isn’t quite as comprehensive as you would like - or if you want an exercise less demanding on your flexibility - try the following alternative exercises out.

Decline Crunches

Decline crunches are essentially conventional crunches performed on a decline bench, allowing for a greater range of motion and thereby greater development of the abdominal muscles.

Furthermore, these benefits come alongside the same advantages seen in wall crunches - that is to say, the legs remain locked in place, preventing a breakdown in overall form.

Wall Planks

Wall planks are an advanced variation of plank where the exerciser suspends themselves in a plank position with the legs braced against a wall.

Performing planks in this manner greatly increases the difficulty of the movement while simultaneously enforcing proper form to a stricter degree.

However, unlike the more dynamic wall crunch, wall planks are purely an isometric exercise. As such, they are far better for developing core stability, rather than strength in dynamic contraction or for inducing muscular hypertrophy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Are Wall Crunches Effective?

Absolutely. Wall crunches are considerably more stable and strict than conventional crunches, making them marginally more effective as a whole.

To get the most out of wall crunches, ensure you are controlling the eccentric phase of the repetition. This will ensure maximum abdominal training.

Do Crunches Really Give You Abs?

Not necessarily. Although crunches do indeed work the abs, a visible six-pack is achieved through reducing body fat composition. Generally, this will require a diet alongside a calorically-expensive training plan.

Can Crunches Slim Your Belly?

Although crunches do burn a few calories when performed for multiple sets, it is generally an inefficient way of reducing fat around the belly.

A better way to slim down your belly is to reduce your caloric intake between 200-500 kcal below estimated daily expenditure while simultaneously taking up a resistance training program.

References

1. Schoenfeld, Brad & Kolber, Morey. (2016). Abdominal Crunches Are/Are Not a Safe and Effective Exercise. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 38. 1. 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000263.

2. Rafael F Escamilla, Eric Babb, Ryan DeWitt, Patrick Jew, Peter Kelleher, Toni Burnham, Juliann Busch, Kristen D’Anna, Ryan Mowbray, Rodney T Imamura, Electromyographic Analysis of Traditional and Nontraditional Abdominal Exercises: Implications for Rehabilitation and Training, Physical Therapy, Volume 86, Issue 5, 1 May 2006, Pages 656–671, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/86.5.656