10 Best Upper Body Pull Exercises (with Pictures!)

Whether it’s to build a wider back or directly work your biceps, no proper training program is complete without its own combination of upper body pulling movements.

An upper body pulling exercise is generally defined to be a resistance exercise involving horizontal or vertical force directed through the muscles of the back. These movements are primarily performed so as to train the pull muscles of the body, and are most likely already present in your workout regimen.

Good examples of upper body pull exercises are pull-ups, chin-ups, bent over rows, shrugs, bicep curls, face pulls and inverted rows.

What are Upper Body "Pull" Exercises?

It can be difficult to actually ascertain whether an exercise belongs in the “upper body pull” category, as they vary widely in terms of muscular recruitment, equipment used and even general mechanics.

However, a good starting point is the direction in which force is exerted during the movement. If it involves pulling an object towards or behind the body - or the body towards an object - then it is likely a pulling exercise.

If the direction of force is not a good indicator, another way of determining whether the exercise is an upper body pull is to see what muscles it works.

What Muscles do Upper Body Pulling Exercises Work?

Although it will vary between exercises, most upper body pulling movements target musculature like the biceps brachii, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, erector spinae or posterior deltoid head.

Horizontal vs Vertical Upper Body Pulling Movements

These exercises are the counterpart to upper body pushing exercises, and are often divided according to whether they are a vertical pulling exercise or a horizontal pulling exercise.

As you may have already guessed, horizontal and vertical pulling exercises are differentiated according to what direction the musculature is pulling towards.

The most common types of vertical pulling exercises are variations of the pull-up, pull-down or shrug. These sorts of exercises will generally target the trapezius and latissimus dorsi, and frequently involve movement of an object along a vertical path in order to execute correctly.

In comparison, the most frequently encountered horizontal pulling movements are primarily variations of the row, but may also come in the form of face pulls or the bodyweight inverted row.

Horizontal pulling exercises are more likely to target the rhomboids, posterior deltoid head and other mid-back muscles than their vertical counterparts, and likely involve moving an object along a horizontal axis.

What are the Benefits of Doing Upper Body Pulling Exercises?

While it will indeed depend on what specific exercise is in question, most pulling exercises can offer the following benefits when performed in regularity.

Builds Mass and Strength in the Pull Muscles

The “pull” muscles of the upper body are much the same as those mentioned early in this article - those being the muscles of the back, posterior deltoid head and the flexor muscles of the arms.

With proper programming and the support of sufficient recovery, performing upper body pulling exercises will build both mass and strength in such muscle groups. Lifters seeking larger biceps, a wider back or more prominent traps absolutely require pulling exercises to achieve their goals.

Numerous Variations to Try

Most (if not all) upper body pulling exercises feature several variations that alter some key aspect.

These variation exercises are developed to help create a more targeted workout plan, increase training intensity or otherwise make the movement more accessible to perform.

If you find that you do not have the equipment to do a specific exercise - or wish that it would better emphasize a certain muscle group - it is likely that there is a variation that addresses your exact needs.

Improves Posture, Upper Body Stability, and Flexibility

In order to maintain proper posture and upper body stability, strengthening the muscles of the back is especially important.

The latissimus dorsi and posterior deltoids are particularly pivotal in maintaining the correct position of the shoulders and scapula, and muscles like the erector spinae and other lower back musculature are vital for stabilizing the entire torso as antagonist muscles.

In addition to their postural and stability improvements, regularly performing upper body pulling exercises will also develop the flexibility of non-muscular tissue found in many of the upper body’s joints - adding further benefit to their performance.

Develops Important Athletic Skills and Competencies

Like other forms of resistance exercise, performing upper body pulling movements will build many of the skills and capabilities needed by athletes, regardless of their sport.

Whether it be stronger biceps, better bodily control or greater muscular endurance, it is likely that performing pull exercises will only help further the athlete’s abilities.

Upper Body Pull Exercises

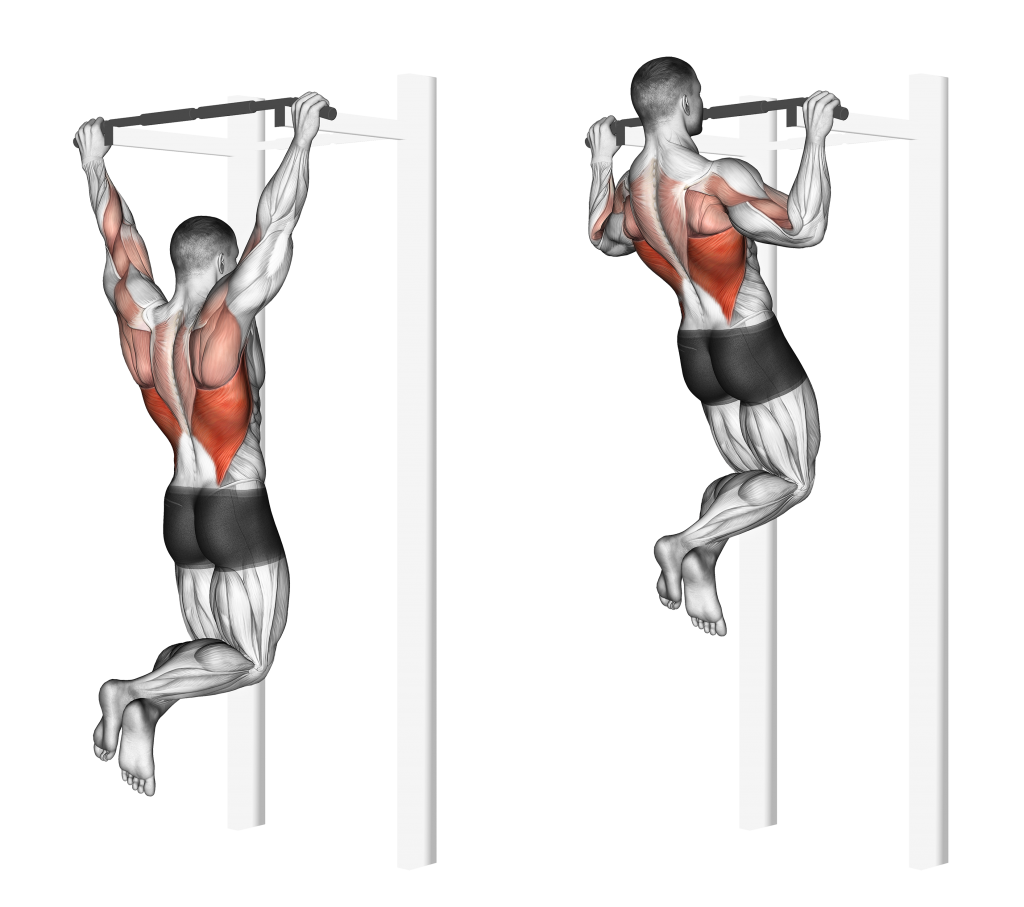

1. Pull-Ups

Pull-ups are the quintessential vertical pulling exercise - featuring a compound movement pattern and bodyweight resistance meant to target the latissimus dorsi, biceps and other back muscles at a high level of intensity.

Equipment Needed

Pull-up bars require only an overhead bar. At the later stages of training, athletes may make use of wearable weights to continue their progression.

Muscles Worked

Pull-ups work the latissimus dorsi, biceps brachii, posterior deltoid head, rhomboids and core.

How-to:

To perform a repetition of pull-ups, the lifter will grip a pull-up bar overhead in a double overhand grip, hands set wider than shoulder-width apart.

Contracting their lats and squeezing their core, the lifter will then bend at the elbows as they draw themselves towards the bar, stopping once it is below their chin.

From this point, they will simply reverse the motion in a slow and controlled manner to complete the repetition.

2. Chin-Ups

The more biceps-focused counterpart to the pull-up; chin-ups are a vertical pulling exercise traditionally performed with only the lifter’s own weight as a source of resistance.

Chin-ups are classified as a compound exercise involving recruitment of the latissimus dorsi, biceps brachii and other upper body pulling muscles.

In comparison to pull-ups, chin-ups involve an underhand grip, a slightly shorter range of motion and greater accessibility to novice calisthenics athletes.

Equipment Needed

Chin-ups require only an overhead pull-up bar.

Muscles Worked

The chin-up exercise primarily targets the biceps brachii and latissimus dorsi, but will also work the posterior deltoid head, rhomboids, teres muscles and the trapezius.

How-to:

To perform a repetition of the chin-up, the lifter will grasp a pull-up bar overhead with both hands set in an underhand (supinated) orientation, shoulder-width apart.

Then, squeezing the latissimus dorsi and stabilizing the body with the core muscles, the lifter will draw their chest towards the pull-up bar.

Once their head has cleared the bar, they may carefully return to the starting position in a controlled manner - thereby completing the repetition.

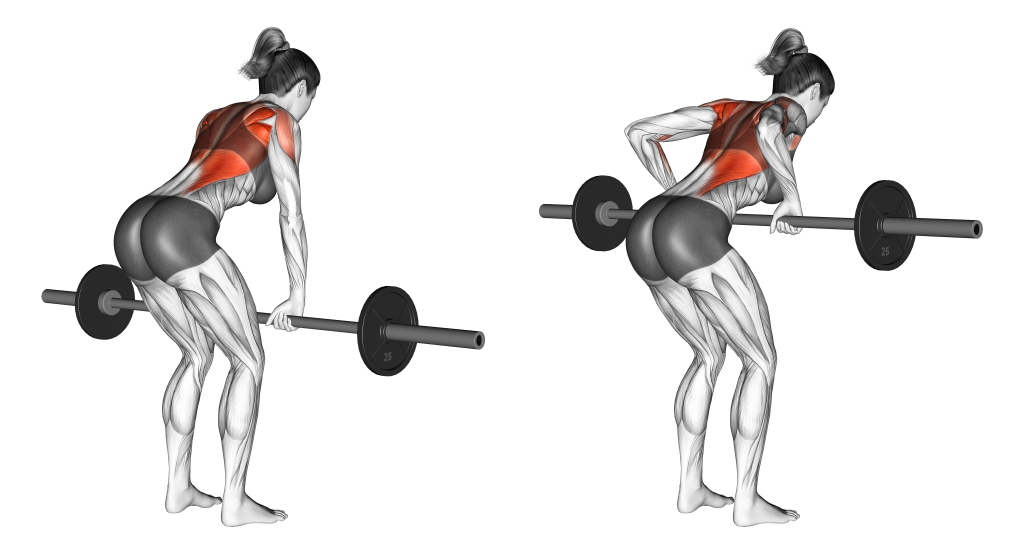

3. Bent-Over Rows

One of the most iconic horizontal pulling exercises is the bent-over row.

A traditionally free weight compound exercise meant to build thickness in the back, the bent-over row is most often used to build thickness and gross muscular strength in the mid-back and arms by athletes and bodybuilders alike.

Equipment Needed

The traditional variation of the bent-over row requires a barbell and a set of weight plates, although many lifters also perform it with the use of dumbbells or kettlebells.

Muscles Worked

Bent-over rows are a wide-reaching compound movement, and as such will target the rhomboids, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, teres muscles, erector spinae and the elbow flexor muscles of the arms.

How-to:

Contracting the core and hinging forward at the hips as they grip a barbell in both hands, the lifter will keep their arms close to the sides of the torso as they draw their elbows behind their torso - ensuring that the lower back is kept straight and the shoulder blades retracting alongside the elbows.

Once the bar is considerably close to touching the sternum or chest, the lifter will slowly extend their arms back beneath the torso to complete the repetition.

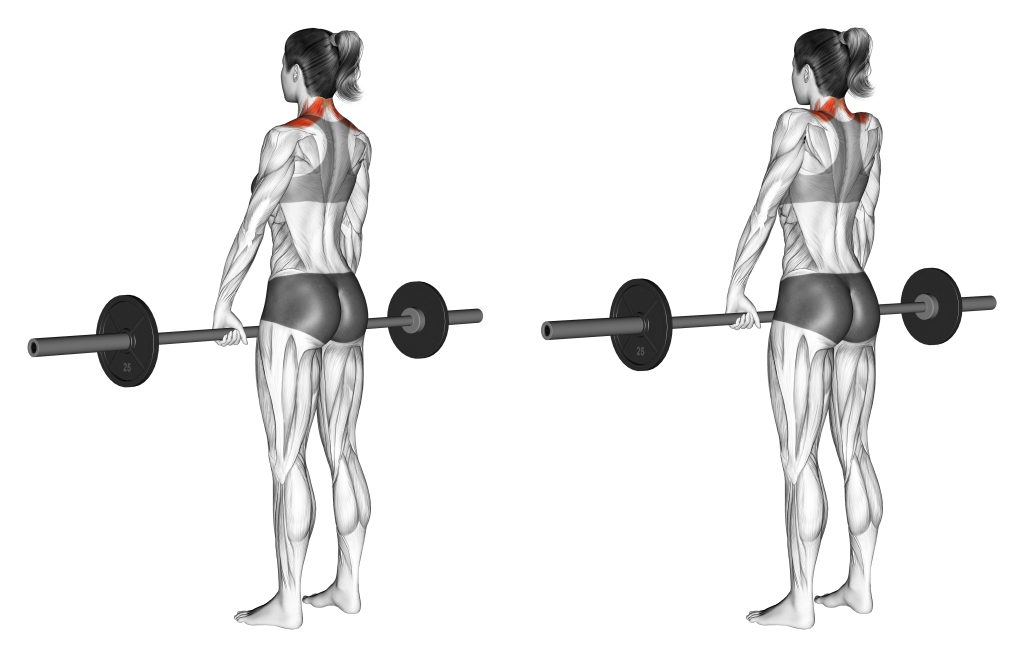

4. Shrugs

Also known as “trap shrugs”, the conventional shrug exercise is an isolation movement meant to target the trapezius muscles atop the shoulders with highly-focused training volume.

Shrugs are frequently programmed as an accessory to heavier back muscle exercises, and are classified as a vertical pulling movement.

Equipment Needed

Shrugs are generally performed with a loaded barbell or a pair of heavy dumbbells.

Muscles Worked

Shrugs are an isolation exercise primarily recruiting the trapezius, although the deltoids also play a supporting role.

How-to:

Gripping the barbell at the front of the body (or at the sides, for dumbbells) in a double overhand grip, the lifter will position their shoulders in a neutral rotation and ensure that the neck is aligned with the spine as they begin to perform the repetition.

To do so, they will simply draw their shoulders upwards and towards the sides of their head, stopping once the trapezius muscle is sufficiently worked.

From this point, the lifter will simply drop their shoulders back to their original position so as to complete the repetition.

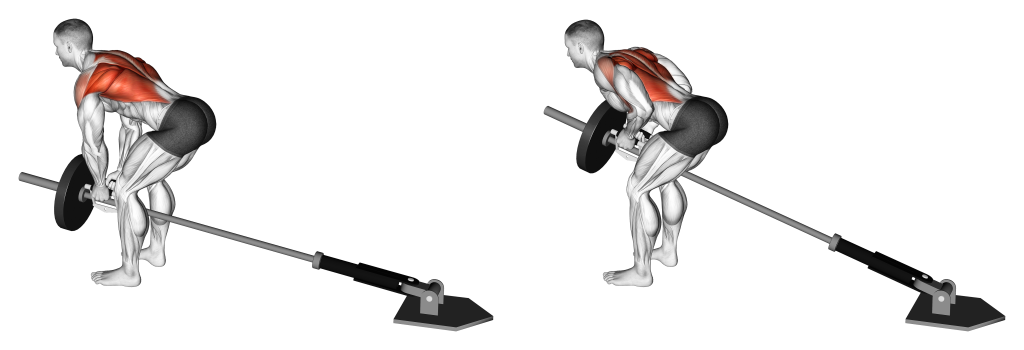

5. T-Bar Rows

The T-bar row is a variation of the conventional bent-over row where a T-bar handle is affixed to the barbell. Doing so allows the exercise to be performed with a neutral grip, producing greater emphasis on the muscles of the middle-back.

Like other heavy row exercises, the T-bar row is a horizontal pulling exercise classified as a free weight compound movement, and is frequently programmed as the primary exercise in many pull day workout sessions.

Equipment Needed

T-bar rows require a T-bar handle, a landmine attachment (optional), a barbell and a set of weight plates.

The aforementioned landmine attachment may be used to stabilize the opposite end of the bar.

Muscles Worked

T-bar rows primarily work the latissimus dorsi, lower trapezius and rhomboids, but will nonetheless also target the rest of the back’s musculature - including the erector spinae and posterior deltoid heads.

In addition, the biceps brachii, brachialis and brachioradialis muscles of the arms are worked as well.

How-to:

Hinging at the hips with the core contracted and the spine in a neutral curvature, the lifter will hold both ends of the T-bar handle in a neutral grip, facing the head forward so as to align the c-spine with the entirety of the spinal column.

To perform the repetition, the lifter will contract their lats and pull their elbows behind their body - striving to keep the arms close to the sides as they do so.

Once the bar is sufficiently close to touching the torso (or the scapula is completely retracted), the lifter will reverse the motion and allow their arms to extend beneath their body once more.

From this point, the repetition is considered to be complete.

6. Cable Machine Rows

For a safer and more hypertrophy-focused variation of the conventional row, lifters may instead switch to the machine-based cable row.

Like other row variations, the cable row is a horizontal pulling movement classified as a compound exercise, and is considered to be quite effective at building both mass and strength throughout the back.

Equipment Needed

Cable rows will require a cable machine and a two-handed attachment.

Muscles Worked

Machine cable rows primarily work the latissimus dorsi, but summarily also target the trapezius, rhomboids, teres muscles, posterior deltoid head and the elbow flexor muscles of the arms.

How-to:

To perform a repetition of cable rows, the lifter will sit with their chest pushed out and their shoulders in a neutral position, arms extended in front of them as they grip the machine’s handles.

From this position, the lifter will simultaneously retract their scapula and draw the handle towards their chest, pulling the elbows to the sides of the torso.

Once reaching the limit of their range of motion, they will allow the resistance to slowly pull their arms back to a state of full extension - thereby completing the repetition.

7. Machine Lat Pulldowns

A vertical pulling compound exercise primarily programmed as an accessory movement - the lat pulldown replicates the mechanics of a conventional pull-up without the need for the lifter to suspend themselves or otherwise lift the entirety of their own body’s weight.

Equipment Needed

The lat pulldown requires a lat pulldown machine (or compatible cable machine) as well as a sufficiently wide bar handle.

Muscles Worked

Lat pulldowns primarily work the latissimus dorsi, but also target the trapezius, posterior deltoid head and biceps brachii.

How-to:

Sitting within the lat pulldown machine, the lifter will grip the handle overhead with their hands set slightly wider than shoulder-width apart and in a pronated orientation.

Keeping the torso upright, they will begin the repetition by contracting their lats and pulling the bar downwards, drawing their elbows to the sides of their torso.

Once the bar is beneath the chin, the lifter will slowly reverse the motion and return the bar to its original position overhead.

At this point, the repetition is considered to be complete.

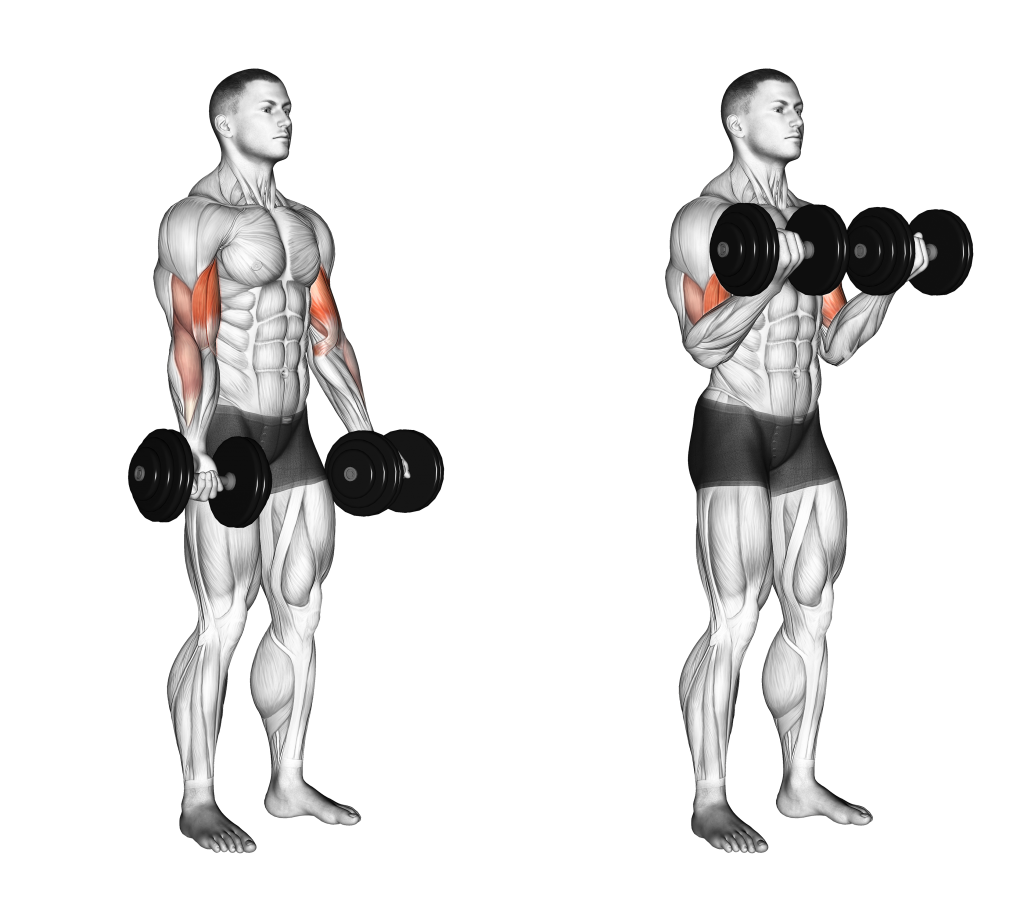

8. Bicep Curls

The bicep curl is an iconic vertical pulling exercise involving a single-joint movement pattern and isolated recruitment of the biceps brachii. It is most often used to round-out the training volume of a workout session in the context of being an accessory exercise.

Equipment Needed

Bicep curls are most often performed with a pair of dumbbells, but can also be done with an EZ-barbell, straight barbell or pair of kettlebells.

Muscles Worked

Bicep curls are an isolation exercise - meaning that they solely target the biceps brachii.

How-to:

Standing upright with a pair of dumbbells held at the sides of the hips, the lifter will keep their elbows stationary against the sides of the torso as they contract their biceps and draw the dumbbells upwards.

Once the dumbbells are at the same elevation as the lifter’s shoulders, the lifter will reverse the motion and return their hands back to their original position, ensuring that tension is maintained in the biceps.

From this point, the repetition is considered to be complete.

9. Face Pulls

The face pull is a machine-based horizontal pulling exercise meant to reinforce and strengthen the shoulders, trapezius and scapula with a low-to-moderate level of training intensity.

It is primarily considered to be a compound exercise programmed in a supplementary role - although it also sees some use in physical rehabilitation as well.

Equipment Needed

Face pulls require a cable machine and double-ended rope attachment.

Muscles Worked

When performed correctly, face pulls target the entirety of the deltoids, the teres major, the trapezius, the infraspinatus and the brachioradialis.

How-to:

Standing upright with the cable pulley set at face-height, the lifter will grip both ends of the rope with their shoulder blades in a neutral position and their arms extended in front of them.

To begin the repetition, the lifter will retract their shoulder blades as they flare their elbows outwards, drawing them parallel to the shoulders and the cable handle immediately towards their face.

Once the hands are parallel with the sides of the head, the lifter will simply reverse the motion to complete the repetition.

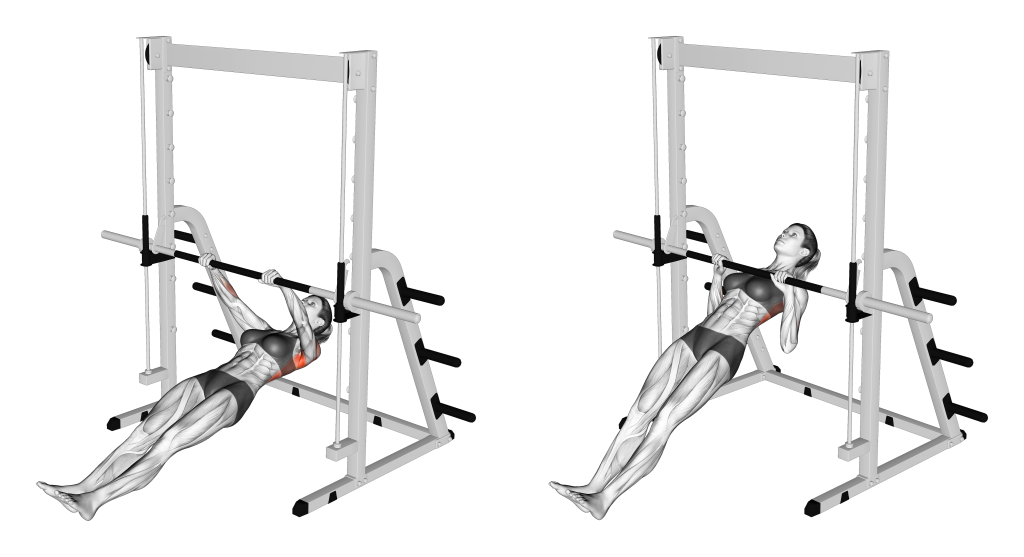

10. Inverted Rows

Also known as a bodyweight row - inverted rows are a horizontal pulling exercise where the lifter will suspend themselves a few feet off the ground so as to target the back, core and biceps.

Like other row exercises, the inverted row is a compound movement primarily involving elbow flexion and scapular retraction. However, unlike its weighted counterparts, inverted rows are most often performed for high volume sets due to their inherently low-to-moderate level of intensity.

Equipment Needed

Inverted rows require either a racked barbell, gymnastic rings close to the ground, or a sufficiently stable object for the lifter to suspend themselves from.

Muscles Worked

Inverted rows primarily target the latissimus dorsi and rhomboids, but will also hit the biceps brachii, teres, infraspinatus, trapezius and the core.

How-to:

To perform an inverted row, the lifter will suspend themselves from a barbell or pair of gymnastic rings with their chest facing upwards and their legs extended away from the torso for greater stability.

The rings or barbell should be held in a double overhand grip at slightly wider than shoulder-width apart.

From this position, the lifter should be hanging from the barbell with their arms fully extended, yet their torso should be suspended off the floor so as to maintain tension.

To begin the repetition, the lifter will simply bend at the elbows, contract their core and back musculature and draw their torso towards the bar.

Once the chest touches the bar, the repetition is considered to be complete.

Which Upper Body Pulling Exercise is Right for You?

In order to pick the best upper body pulling exercise for your needs, you’ll first need to identify which muscle groups you want to target - and to what intensity this exercise should be performed.

Once you know what muscles to work (and how hard), it is only a matter of equipment availability and personal preference.

Remember to perform all your exercises with proper form, and to consult a professional if you are unsure of any aspect of your training.

References

1. Westcott, Wayne., Baechle, Thomas R.. (May 4 2015) Strength Training Past 50. United States: Human Kinetics, 2015.

2. Lorenzetti, Silvio, Romain Dayer, Michael Plüss, and Renate List. 2017. "Pulling Exercises for Strength Training and Rehabilitation: Movements and Loading Conditions" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 2, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk2030033