T-Bar Row vs Barbell Row: Differences Explained

If you are a novice, have a sensitive lower back or otherwise wish to better isolate the muscles of the upper and middle back; the t-bar row is a better choice.

Otherwise, if you wish to build overall strength, improve lower back stability or maximize ROM; the conventional barbell row is superior.

T-Bar vs. Barbell Row: Stance Differences, Loading Capacity and Range of Motion

Though nearly identical, both variations of row differ in terms of minute stance characteristics, how much weight can be loaded and even the actual range of motion of the entire movement itself.

Stance Differences

The barbell row will involve a somewhat more horizontal trunk orientation than is traditionally used with a t-bar row.

Likewise, the t-bar row will also tend to involve a closer hand positioning and subsequently a more tucked elbow position at the apex of the repetition.

Depending on individual injury history and proportions, either differences in stance may make the opposite exercise more advantageous.

Maximal Loading

Due to the more upright trunk angle, closer grip and distribution of load, the t-bar row allows for somewhat more weight to be lifted than the conventional barbell row.

For strength athletes or those seeking load-driven incremental progression, the t-bar row is a better choice.

Total ROM

T-bar rows tend to be limited by the diameter of the plate loaded at the end of the bar. The larger the plate, the sooner the concentric phase of the repetition ends, and the less specific muscle groups are targeted.

In combination with the limited elbow flexion angle and more upright trunk orientation, the t-bar row features a significantly smaller range of motion than is seen with conventional bent-over barbell rows.

T-Bar vs. Barbell Row: Muscular Emphasis and Strain Considerations

Even small differences in stance and range of motion can alter the recruitment pattern of an exercise.

The t-bar row and barbell row are no different, with their injury risk and secondary mobilizer activation being distinct as well.

Secondary Mobilizer Involvement

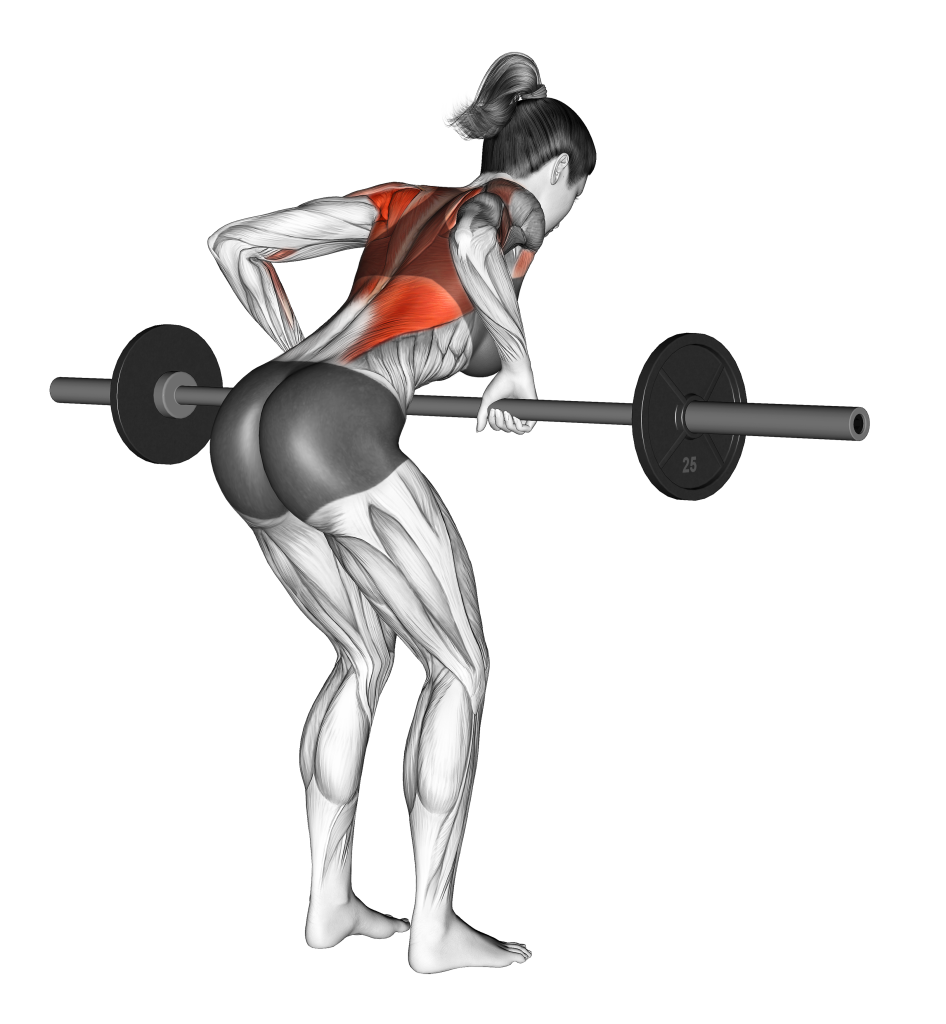

The barbell row will tend to target the erector spinae, lower back stabilizers and even the hamstrings in an isometric capacity.

In comparison, the t-bar row will place ever so slightly greater emphasis on the brachialis and brachioradialis on account of its non-pronated grip.

That being said - across the board, the two exercises will target all major back muscles (lats, traps, etc.) to a similar degree.

Risk of Injury, Fatigue Accrual and Complexity

With its more complex positioning and greater range of muscles recruited, the barbell row is both more fatiguing and somewhat more likely to result in injury when performed with poor technique.

In particular are those susceptible to lower back injury - of which can fall into a compromised state when poor core bracing and hip positioning is present.

For novices or those performing their rows as a secondary compound movement, the t-bar row may be a safer choice.

T-Bar vs. Barbell Row: Applicability

Which Exercise is Better for Mass Development?

In terms of isolating the upper back with comparatively less fatigue, the t-bar row may be a superior choice - eventually leading to a greater potential for hypertrophy.

Of course, the larger range of motion featured by the barbell row counterbalances these advantages.

As such, it ultimately comes down to whether the lifter’s volume is limited by lower back fatigue and injury risk.

Which Exercise is Better for Strength Training?

Outside of highly specific strength accessory work, the conventional barbell row is a far better choice for general strength development.

By featuring a larger range of motion and more functional recruitment pattern (including the back stabilizers) - the barbell row allows lifters to better develop horizontal pulling strength, regardless of positioning.

Can You Do Both the T-bar and Barbell Row?

It is indeed possible to perform both the t-bar and barbell row within the same training program, so long as the more fatiguing and complex barbell row is given precedence over the safer and easier t-bar row.

References

1. Fenwick, Chad M J et al. “Comparison of different rowing exercises: trunk muscle activation and lumbar spine motion, load, and stiffness.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 23,2 (2009): 350-8. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181942019