Suitcase Deadlifts: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

The suitcase deadlift is an “odd” lift most often employed for improving core strength and overall functional pulling power on one side of the body.

Although delicate in regards to lower back health - if performed correctly, it can be an effective and highly specialized tool for powerlifters and similar types of athletes.

What are Suitcase Deadlifts?

Suitcase deadlifts are a free weight unilateral pulling exercise involving the lifter performing an otherwise ordinary deadlift with the weights placed parallel to the side of one leg.

In actual training, suitcase deadlifts are rarely ever used as a heavy primary lift. Instead, they fulfill more of a skill-specific or corrective role, aiding in uneven pulling strength, building one-sided core strength or refining the lifter’s overall deadlift technique.

Because of the suitcase deadlift’s uneven distribution of weight, a significantly lower load should be utilized in comparison to conventional deadlifts. Furthermore, the utmost level of attention should be paid to moving both sides of the body (with proper form) in an even and balanced manner.

Are Suitcase Deadlifts the Right Exercise for You?

Suitcase deadlifts require an already well-established understanding of deadlift technique. They are not suitable for novice lifters - and may be too specific for general weightlifting purposes.

Those who will benefit most from suitcase deadlifts are strength athletes with the aforementioned issues in physiology or technique, or otherwise lifters that wish to train unilateral power and stability at a high intensity.

Avoid suitcase deadlifts if you have a history of injuries in the back, spine, trapezius, knees, shoulders or abdominal area. Speak to a medical professional prior to attempting the exercise.

How to Do Suitcase Deadlifts

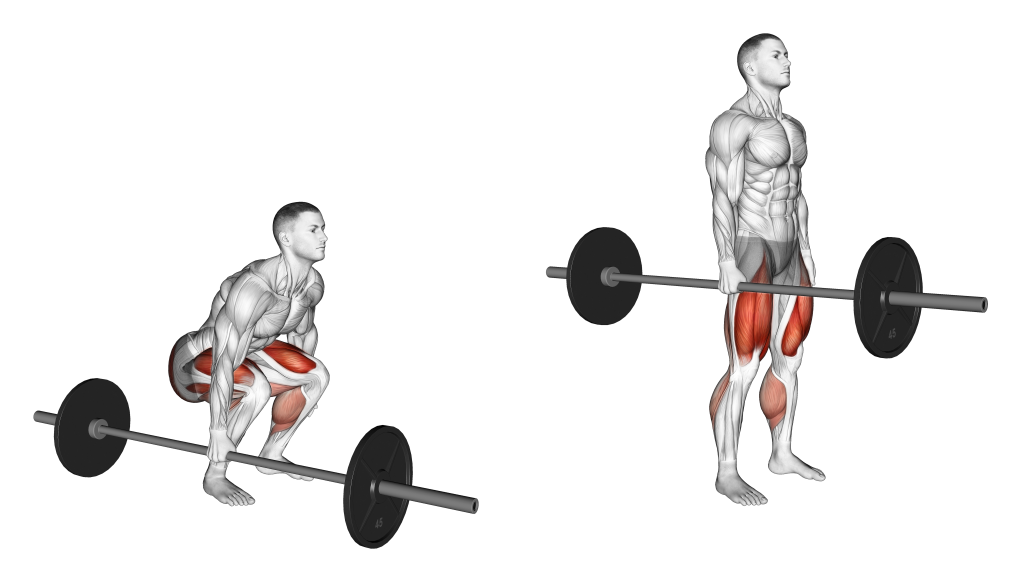

To perform a repetition of the suitcase deadlift, the lifter will first place a loaded barbell beside the shin of their working leg, ensuring their feet are parallel and their entire body is facing forwards in relation to the toes.

Hinging forward at the hips and bending the knees slightly (as per a standard deadlift), the lifter then grasps the barbell with the hand of the same side in a pronated grip. The torso should remain perfectly even and balanced, with no tilting towards the working side whatsoever.

Bar now held in one hand, the lifter then drives through their heels, extends their knees and pushes their hips forwards so that they rapidly rise into a standing position.

Avoid hyperextending the back and causing the torso to tilt backwards. This is a highly common mistake that does not improve muscular development, only increases the risk of lower spine compression.

Now completely upright with the weight held around the side of the thigh, the lifter then slowly reverses the motion by pushing their hips back and bending at the knees once more - returning the bar to the ground.

At this point, the repetition is considered to be complete. Don’t forget to also train the other half of the body in equal measure.

Sets and Reps Recommendation

For lifters with an already well-established understanding of deadlift technique, suitcase deadlifts may be performed for 3-5 sets of 6-12 repetitions, ensuring both sides are worked with the same volume.

What Muscles are Worked by Suitcase Deadlifts?

Suitcase deadlifts are what is known as a “compound” exercise, meaning that multiple joints are involved and subsequently multiple muscle groups as well.

These muscles are classified according to the type of contraction they exhibit during the movement, with eccentric or concentric contraction signaling a “mover” or “mobilizer” muscle, and static or isometric contraction meaning that the muscle is a “stabilizer”.

The suitcase deadlift is rather unique among deadlift variations as it targets the same mover muscles, but inherently requires vastly greater isometric strength and control due to the one-sided nature of the movement.

Mover Muscles

Suitcase deadlifts target much the same muscle groups as conventional deadlifts as far as dynamic contraction goes.

Essentially, this means that the main muscles involved are the gluteal muscles, the hamstrings and the quadriceps femoris - all of which are located in the lower body and aid with extension/flexion of the knees and hips.

Stabilizer Muscles

The suitcase deadlift contracts the core muscle group as the main stabilizer muscles of the exercise, often to a highly intense degree. These muscles include the internal and external obliques, the various superficial and internal abdominal muscles, those of the lower back and the spinal erectors.

Apart from the more traditional stabilizing muscle group that is the core, suitcase deadlifts also contract the deltoids, forearms, trapezius and the latissimus dorsi.

Of course, such isometric contraction is considerably more intense on the opposite half of the working side, as the muscles will need to work harder to keep the body in an even stance.

What are the Benefits of Doing Suitcase Deadlifts?

When performed correctly, suitcase deadlifts can be a boon for developing asymmetrical strength, specific aspects of deadlift technique and overall strength and stability throughout the body.

Excellent for Developing Grip and Core Strength

The main advantage to performing suitcase deadlifts is its capacity to improve core and grip strength in both a dynamic and isometric capacity.

During a suitcase deadlift, the core muscles will work comparatively harder than in other deadlift variations to keep the body stable and balanced. Muscles like the obliques and abdominals will contract isometrically to aid the main mover muscles and prevent the torso from rotating towards the working side.

Likewise, the fact that a heavy weight is held in only one hand is considerably taxing on the forearm muscles that are responsible for maintaining a firm grip on the weight itself.

Poor grip strength is a common limiting factor in all variations of deadlift, and the suitcase deadlift can be a highly effective way of pushing such limits.

This sort of muscular strength is vital for greater safety during conventional deadlifts and general movement as a whole.

Improves Deadlift Technique - Anti-Rotation Mechanics and Pulling Power

Issues with conventional deadlift technique like bar rotation or an uneven pull can be corrected by the rather specific movement pattern inherent to suitcase deadlifts.

Because the bar is present on only one side of the body, the lifter will be forced to work harder to prevent the bar from rotating as it is held in their grip - in addition to also preventing their own body from rotating as well.

Furthermore, the unilateral pulling pattern involved will help the lifter reach a more refined understanding of their own mechanics on each side.

If you frequently find that one side rises before the other during a conventional deadlift, suitcase deadlifts can be effective for strengthening the lagging side.

Builds Overall Stability, Asymmetrical Strength and Balance

As a result of stronger stabilizer muscles and greater pulling technique, lifters who regularly perform suitcase deadlifts will find that their overall muscular stability is improved as well.

This benefit comes hand in hand with the asymmetric strength development that is also firmly developed - an aspect of training often overlooked in conventional strength training movements.

With improved one-sided strength and greater muscular stability as a result of stronger core muscles, the lifter’s capacity to maintain their balance (even during heavy lifts) will be enhanced alongside.

Of course, to get the most out of the suitcase deadlift in the vein of these benefits, consider combining the exercise with other forms of isometric and asymmetric exercise, like planks or lunges.

Challenging in a Functional and Non-Traditional Manner

Even outside of a pure muscle and technique perspective, the suitcase deadlift can provide a refreshing challenge to lifters who have grown bored with traditional deadlift variations.

While similar enough to achieve much the same muscular recruitment pattern, the position of the weights and unique challenge of performing a unilateral deadlift is an easy way to “shake things up” in your workout, so to speak.

As an added bonus, the sort of developmental benefits provided by the suitcase deadlift are also perfectly geared towards more functional activities. The conventional deadlift movement pattern is practiced far less widely than that of the suitcase deadlift - at least outside of an athletic or training environment.

Carryover to One-Legged Deadlifts, Pistol Squats and Jefferson Deadlifts

Because of their shared asymmetrical stance and unilateral distribution of load, the suitcase deadlift can be quite effective for improving the lifter’s performance in exercises of a similar nature.

The most applicable of these are similar lower body exercises involving a displaced distribution of load, such as with pistol squats, one-legged deadlifts or even the less common Jefferson deadlift. Other movements like weighted lunges, lateral sled drags and one sided kettlebell swings also benefit in a similar manner.

With regular performance of the suitcase deadlift, the lifter’s stability, coordination and overall comfort with performing asymmetric movements such as the aforementioned will only be further enhanced.

Common Suitcase Deadlift Mistakes to Avoid

In order to minimize the risk of injury during a suitcase deadlift set, avoid the following common errors in technique.

Rotating the Torso or Leaning to the Side

As mentioned previously in this article, leaning the torso to the side at the waist or otherwise rotating the body towards the bar can easily lead to injury, even with small amounts of weight.

Such risk is a result of rotational force placed on the lower spine and its surrounding back musculature, of which can easily twist and tear if this rotational force is significant enough.

To avoid making this mistake, the lifter should prioritize their torso orientation above all else in the exercise. The chest should always be facing in the same direction as the feet, and the waist perfectly aligned with the front of the hips at the end of the repetition.

Poor Hip Hinging

A common mistake in practically all forms of deadlift; poor usage of hip hinging can turn the movement into a sort of squat, reducing posterior chain recruitment and straining the lower back in certain cases.

This is especially an issue with the suitcase deadlift, as failing to hinge forwards at the hips can increase strain on the knees and make actually pulling the weight off the floor far more difficult.

To properly hinge for a deadlift, the lifter must push their glutes backwards while simultaneously allowing the torso to lever forwards at the hips, stretching the hamstrings slightly as they do so. The knees should also be bent in tandem with this hinging.

Curving the Middle or Lower Back

In addition to poor hip hinging, the lifter must also pay close attention to the curvature of their middle and lower back.

While some level of upper back curvature is needed to properly pull the bar off the floor, curving the middle and lower back at any point will inevitably lead to injury and poor muscular recruitment.

In order to prevent this type of mistake, the lifter should learn to properly brace their core by contracting their abdominal muscles as they perform a diaphragmatic breath. Bracing correctly provides ample “scaffolding” with which the lower back may remain in a neutral position.

Apart from bracing the core correctly, the lifter should also become familiar with the overall feeling of having a neutral middle and lower back as well.

Practice through lightweight conventional deadlift repetitions may be needed.

Insufficient Range of Motion or Poor Tempo

A common mistake in practically all forms of resistance exercise, failing to complete a full range of motion can lead to poor muscular development, sticking points and even injury with heavy exercises like the deadlift.

Likewise, a poor tempo involves the range of motion performed too rapidly, often with excessive momentum as a cause.

Much like a short range of motion, a poor tempo can also lead to injury and overall poor development as the muscles are not taxed to the same length of time under tension.

For the suitcase deadlift, both mistakes must be corrected in order to properly engage the posterior chain muscles and prevent injuries of the lower back.

Begin and end each repetition in a bent-over hinged position, and ensure that the knees and hips are extended at the top of the movement.

Complete this range in a slow and controlled manner during the concentric phase, controlling the descent of the bar during the eccentric.

Bar Starts Too Low to Reach Safely

When using particularly small plates or weighted objects other than a barbell, the handle may be too low for the lifter to easily grasp while maintaining a balanced deadlift stance. This can pull them out of the correct stance and lead to an uneven initial pull, leading to injuries and a loss of balance.

The bar should be around mid-shin height, elevated through the use of blocks or plates if needed.

Alternatives and Variations of the Suitcase Deadlift

If the suitcase deadlift is contraindicated with any issues in your physiology - or if you want a more balanced exercise - try the following alternatives and variations out.

Double Suitcase Deadlifts

The double suitcase deadlift is exactly as it sounds; conventional suitcase deadlifts performed with both sides of the body loaded, rather than just one.

Mechanically and from a muscular standpoint, this exercise is practically identical to the neutral grip trap bar deadlift, and will utilize much the same technique as well.

For lifters who don’t quite care about the conventional suitcase deadlifts balance, asymmetrical strength and stability benefits, the double suitcase deadlift may be a safer pick.

Deficit Deadlifts

Deficit deadlifts are a form of barbell deadlift performed with the lifter elevated higher off the floor, requiring them to bend further down in order to pull the bar off the ground.

Much like suitcase deadlifts, deficit deadlifts are performed so as to refine the lifter’s conventional deadlift technique and overall bodily stability.

Unlike suitcase deadlifts, deficit deadlifts are bilateral and symmetric in technique, meaning that none of the same risks of injury are present - a bonus, considering the deficit deadlift’s larger range of motion as well.

Jefferson Deadlifts

Jefferson deadlifts are a similarly “odd” form of deadlift where the bar is placed between the legs of the lifter as they pull in a staggered, nearly lunge-like stance.

Jefferson deadlifts are considerably easier on the spine, and are also employed in a similar manner to suitcase deadlifts during skill-specific training of powerlifters and strongman competitors.

In particular, they are frequently used to build asymmetric strength, especially in cases where one side of the body is pulling more powerfully than the other during conventional deadlifts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Are Suitcase Deadlifts Effective?

In certain aspects - yes. Suitcase deadlifts are great for building asymmetric strength, balance, deadlift technique and core stability.

Can You Do a Suitcase Deadlift With Dumbbells?

Yes. Although the traditional form of suitcase deadlift involves a plate-loaded barbell, dumbbells can also be used in a similar manner granted that they are high off enough the ground to pull safely.

Is the Suitcase Deadlift Better Than the Deadlift?

Not quite. Suitcase deadlifts are far more situational and skill-specific than their conventional counterpart, and are nowhere near as heavy or as effective at building lower body muscle mass and strength.

References

1. Hindle BR, Lorimer A, Winwood P, Keogh JWL. The Biomechanics and Applications of Strongman Exercises: a Systematic Review. Sports Med Open. 2019 Dec 9;5(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s40798-019-0222-z. Erratum in: Sports Med Open. 2020 Feb 5;6(1):8. PMID: 31820223; PMCID: PMC6901656.

2. Kalata M, Maly T, Hank M, Michalek J, Bujnovsky D, Kunzmann E, Zahalka F. Unilateral and Bilateral Strength Asymmetry among Young Elite Athletes of Various Sports. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Dec 10;56(12):683. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120683. PMID: 33321777; PMCID: PMC7764419.