Squat Holds: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

For building endurance, static strength and lower body mobility, the squat hold is one of the most convenient exercises possible.

As you can likely guess from its name, squat holds quite literally involve sinking into a squat and holding a specific depth for a predetermined length of time.

Apart from building endurance and static strength, squat holds are also excellent for relieving tightness in certain muscle groups - as well as improving performance in other squat variations if loaded with sufficient weight, much like box squats do.

What are Squat Holds?

Squat holds are a compound closed chain static exercise traditionally performed with no equipment whatsoever.

Despite this, more advanced lifters (or those with specific training needs) can load the movement with further weight in order to up the intensity of the set.

Squat holds are employed for a truly broad range of purposes, but most often for improving static strength, stability and endurance in the muscles of the legs and core.

Lifters may also use squat holds for improving mobility, indirectly refining their back squat technique or as a non-dynamic warm-up exercise.

Are Squat Holds the Right Exercise for You?

Apart from having too many exercises in your training program, squat holds are perfectly fine for the majority of healthy individuals.

With their wide range of uses, it is simply a matter of playing with their intensity and placement within a workout session.

However, individuals with a history of injury to the knees, ankles, hips or a history of hernias may wish to avoid squatting exercises as a whole.

How to do a Squat Hold

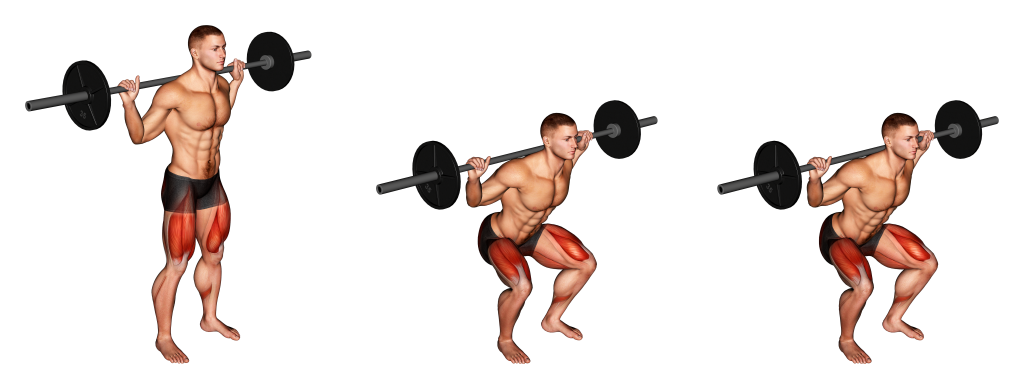

To perform a repetition of squat hold, the lifter will first set their feet approximately shoulder-width apart, bracing the core and maintaining spinal neutrality throughout the hold.

The chest should be pushed out with the head facing forwards and the body’s weight distributed through the heels into the floor.

Now in the correct squat stance, the lifter pushes their hips back and bends at the knees - lowering themselves until the top of their knees is parallel with the crease of their hips.

At this depth (or slightly lower, if desired), the lifter pauses and keeps a steady level of tension in their quadriceps, core and glutes for the predetermined length of time.

Once they have spent a sufficient amount of time in the squatting position, the lifter drives through their heels and stands back up.

When standing upright once more, the repetition is considered to be complete.

Sets and Reps Recommendation

If performing squat holds unweighted, aim for 2-3 sets of up to 5 repetitions, each repetition consisting of a 30-60 second hold.

Otherwise, if performing the exercise weighted for technique refinement or for conditioning to heavy loads, try 3 sets of 8 repetitions, holding for 15-30 seconds each.

What Muscles are Worked by Squat Holds?

Although a compound (multiple muscle) exercise, squat holds are a static movement and as such do not technically have “mobilizer” or “mover” muscles, since no actual dynamic contraction is present during a working repetition.

That being said, the exercise nonetheless still tends to favor major muscles along the anterior plane of the body due to the squat stance being held.

Primary Muscle Worked

Squat holds primarily contract the quadriceps in an isometric manner, as they bear the majority of the body’s weight while the knees are in a state of partial flexion.

Other Muscles Worked

Apart from the quadriceps, squat holds will also work the abdominal muscles, obliques, lower back, erector spinae, calves, glutes and hamstrings to a lesser extent.

What are the Benefits of Doing Squat Holds?

Squat holds serve such a large number of purposes that listing all their benefits would take several articles. However, we’ve covered the most relevant benefits below.

Excellent for Building Strength, Endurance and Stability

The main benefit to performing squat holds is its capacity to develop overall muscular strength, endurance and stability throughout the trunk and legs.

Isometric contraction is the most underutilized form of contraction in general strength training - an unfortunate fact, considering that it directly leads to improvements in muscular endurance and the stability of the entire body outside of the gym.

To get the most out of squat holds, aim to progressively increase the difficulty of the exercise by either lengthening each repetition or adding further resistance.

Improves Squat Depth and Knee/Hip/Ankle Mobility

A major limiting factor to squat depth is often mobility in the ankles or hips - with poor knee mobility being less common but also a potential limitation.

Regardless of where the lifter’s immobility lies, regularly performing squat holds to the limit of their range of motion can help condition the soft tissues of the lower body to squatting to even deeper depths.

While no actual substitute to a proper mobility drill, squat holds can nonetheless be a multi-purpose exercise that helps correct both mobility and muscular weakness in a single exercise.

Strengthens the Entire Core

In order to maintain the squat stance correctly, muscles like the abdominals, obliques, erector spinae and other core musculature are used. They keep the torso at the correct orientation, help maintain stability at the pelvis and allow for a proper breathing to occur.

With how long these muscles are kept tense over the course of a squat hold, it should be no surprise that a secondary benefit of performing squat holds is stronger core musculature.

To get the best results, combine squat holds with more dynamic core isolation exercises like hanging leg raises, reverse hyperextensions and Russian twists.

Carries Over to Other Squat Variations

Powerlifters and other strength athletes may occasionally use weighted squat holds as a method of refining their execution of other squat variations.

Highly technical explosive movements like overhead squats or barbell snatches benefit the most from practicing with squat holds, as the extended isometric nature of the latter movement helps build the capacity for rate of force development during the former exercises.

In addition, lifters that suffer from instability, shifting or plain instability near the maximum depth of back squats can also use squat holds for correcting these issues.

Remember to replicate competition conditions as closely as possible when performing squat holds for these purposes, as per the law of specificity.

If you are a powerlifter correcting back squat issues, load the squat hold with a barbell and replicate the same stance as a back squat.

Can Aid in Recovery, Warming Up or Diagnostics

Outside of muscular strength and rehabilitation, squat holds have also been used to aid in active recovery, warm-up prior to a tough workout or even to diagnose issues with lower body function.

Apart from the far more technical latter purpose, using squat holds for active recovery is as simple as practicing them at a lesser level of intensity during your recovery days. Aim for half the volume and time under tension you’d normally do.

For use as a warm-up, focus less on volume or time in a squat position, and instead on the feeling of exertion in your lower body. Aim to feel “pumped” or physically primed in the quads and glutes, but not to the point where fatigue begins to creep in.

Common Squat Hold Mistakes to Avoid

Although squat holds are quite simple, avoid the following mistakes in order to avoid injury and get the best workout possible.

Failing to Engage Core

Perhaps the most common mistake seen with all forms of squat is poor bracing of the core.

In order to avoid injuries and maximize the stability of the trunk, the lifter should inhale and “pull their navel towards their spine”, thereby contracting the entire abdominal core in a manner that still allows for steady breathing.

Failing to engage the core can lead to hernias, poor upper body stability, affect the lifter’s balance and cause rounding of the back.

Insufficient Depth/Range of Motion

To properly engage the posterior chain muscles, the hips and thighs should be beneath a certain level of elevation - or what is otherwise known as squatting to full depth.

While the exact depth will depend on the lifter’s proportions and mobility, a generally accepted cue is to align the top of the knee with the crease of the hip. This depth is ideal for not only targeting said musculature, but also improving the mobility of all joints involved.

Failing to adopt a full depth can make the exercise needlessly more difficult and otherwise lead to sticking points, poor mobility or uneven muscular recruitment.

Knees Tracking Too Far Forwards

Although not as much of an issue in lifters with excellent knee mobility, the knees tracking too far forwards over the toes can affect balance and create additional stress on the ankle and knee joints themselves.

Aim to lead the squat by pushing the hips back, rather than bending the knees forwards. The torso should also remain somewhat vertical, rather than bent immediately forwards over the knees.

Doing so will help lock in the correct knee position - as well as help the lifter more evenly distribute their weight into the floor through the heels.

Failing to Balance Over Heels

Less a stance issue and more one related to proprioception and balance, failing to vertically distribute the body’s weight through the heels can cause the lifter to roll forwards onto the balls of their feet.

To correct this mistake, aim to sit the hips back while descending into proper depth. Avoid an excessively forward torso orientation, and aim to “screw” the heels into the floor once the right depth has been achieved.

Alternatives to the Squat Hold

If the squat hold isn’t as dynamic as you would like, try the following alternatives out.

Box Squats

Box squats are essentially the more technical cousin of squat holds, where time under tension is traded in for greater explosiveness and power development in the posterior chain.

Essentially, box squats involve the lifter squatting with additional weight onto a box at parallel depth, where they will explosively contract their glutes so as to rise back into a standing position.

Box squats are comparatively better at building muscular explosiveness and power, correcting sticking points and developing gross lower body strength.

As a squat hold alternative, use box squats if your sport or training goals require more than what can be provided by simple time under tension.

Banded Back Squats

Banded back squats are simply conventional barbell back squats with the addition of resistance bands at both ends of the barbell.

As the lifter rises out of depth, the bands are lengthened, creating a more difficult lockout range and leading to greater conventional squat execution in certain respects.

Substitute squat holds with banded back squats if the former is being performed as a technique refining tool for regular squats - especially in the vein of poor stability or difficulty during the concentric phase.

Pause Jump Squats

For a more functional and athletic squat hold alternative, give the pause jump squat a try.

Pause jump squats are essentially regular squat holds performed with the addition of an explosive jump after the hold is completed. Apart from being significantly more challenging, the addition of a jump also teaches the lifter how to properly use their lower body for explosiveness and power.

Perform pause jump squats if squat holds are specifically programmed as a power-builder in your training plan.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Are You Supposed to Hold During Squats?

Whether or not to pause at depth will depend on your specific reason for doing squats.

If you are a powerlifter or wish to maximize emphasis on the glutes, then a pause should indeed be present at full depth.

However, if your sport does not include a necessary pause at depth (or you get a good enough glute workout without one), then a pause will only make the squat harder to do.

How Long is a Good Squat Hold?

A sufficiently well-trained individual should be able to hold a squat position for anywhere between 30 seconds and 1 minute. More advanced athletes have even attempted the “10 minute squat hold challenge”, where they aim to do exactly that.

How Many Squat Holds Should I Do?

Individuals performing squat holds for general physical development should aim to do up to 5 repetitions per set, stretching out each repetition for up to a minute if physically able.

References

1. Oranchuk, Dustin J et al. “Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review.” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports vol. 29,4 (2019): 484-503. doi:10.1111/sms.13375

2. Kitamura, Tetsuro, Yukako Ishida, Shinji Tsukamoto, Manabu Akahane, Tomoo Mano, Yasuyo Kobayashi, Yasuhito Tanaka, and Akira Kido. 2021. "New Training Tasks for Stepwise Loading in Isometric Bodyweight Squat with Active Posture Control" Applied Sciences 11, no. 17: 8151. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11178151