Squat Ankle Pain: Signs, Form Issues, and More

Quite a number of issues can arise from improper squat execution, with one of the more common issues being a sharp pain through the ankles or feet that is worsened with continued performance of the movement.

In the event that you are experiencing ankle pain during or after a set of squats, it is best to cease performing the exercise and to investigate all possible causes so as to reduce the risk of any further injuries developing.

Ankle pain from squats is generally characterized by a poor initial stance and short range of mobility of the feet and ankles - though certain other factors like improper footwear or a lack of warm-up work may also be to blame.

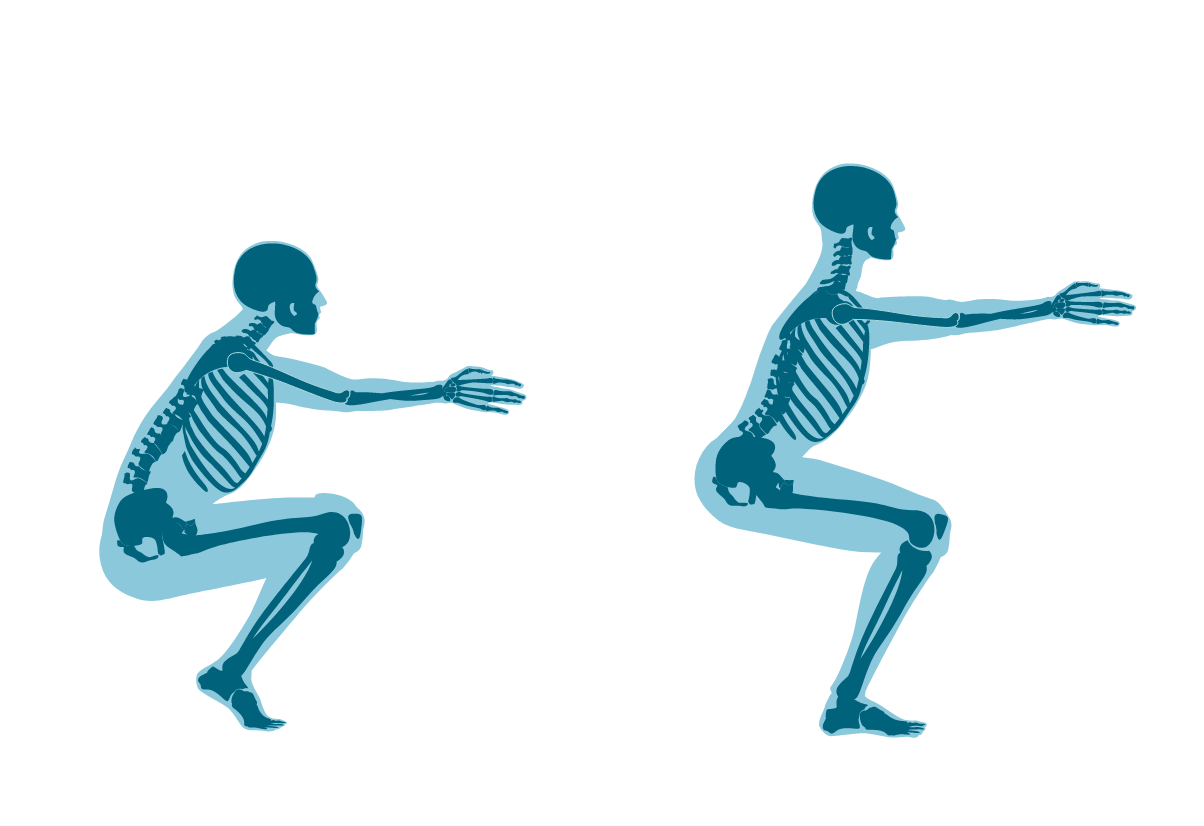

What is the Squat?

In technical terms, the squat refers to the conventional barbell back squat; a free weight compound resistance exercise of the closed kinetic chain variety, usually seen as a staple exercise of nearly every serious bodybuilding or strength-building program.

It is often performed for low volume sets with a moderate to high level of resistance, and makes use of muscle groups like the quadriceps femoris, the entire lower posterior chain and the core muscles.

Anatomy of the Ankle and Foot in Relation to Squats

When speaking of ankle pain during or after squats, it is important to note that ankle pain is rarely isolated to the ankle joint alone, and is often a symptom of issues relating to the foot and calves as well.

During squats, the ankle joint is meant to remain relatively neutral and in-line with the foot and knee joint, with the specific tendon connecting the heel to the bones of the shins (achilles) lengthening significantly as the pelvis drops downwards.

Issues in this particular band of connective tissue - or in the foot’s position in relation to this tendon - will lead to pain and generally poor squat performance as a result.

Furthermore, poor biomechanics like excessive pronation, dorsiflexion or eversion of the foot can pull the ankle out of the intended neutral position, leading to much of the load failing to translate into the ground and thereby damaging the ankle joint itself.

What Does Poor Foot Biomechanics Look Like?

Because of the wide radial movement capable of by the ankles, quite a number of biomechanics may be improperly executed during a squat.

Excessive pronation refers to the ankle rolling inwards during the exercise, of which is often caused by poor footwear or excessive internal rotation being translated into the feet - usually because of a stance that is too wide, or weak hip flexor muscles.

On the other hand, excessive supination will appear to be the ankle rolling outwards in relation to the midline of the body.

While somewhat less common, excessive supination during a squat can be caused by the feet compensating for knee valgus or the muscles of the calves being utilized improperly because of an excessive load being lifted.

Note that a small amount of pronation and supination is entirely normal during the squat, and it is only a cause for concern once the movement becomes excessive and begins to lead to symptoms of pain and instability.

Signs of Tendinopathy of the Ankle Joint

In more severe cases of poor squat execution, a condition known as tendinopathy may be developed.

Tendinopathy is an overuse condition of the connective tissues, primarily characterized by inflammation and damage of tendons connecting muscles to a joint.

For the ankles, this could present as a dull pain regardless of whether pressure is placed on the ankles, or a sharp pain that radiates from the inner portion of the ankle.

Note that pain at the front of the ankle is not the same, and is more indicative of poor mobility rather than tendinopathy.

Tendinopathy of the ankle can also present several other symptoms, such as swelling, a loss of range of motion and a marked worsening of pain symptoms as the causative movement is repeated.

Form Issues of the Squat That can Cause Ankle Pain

Though most issues involving squats and ankle pain are due to poor mobility and conditioning, several errors in squat form can place unneeded stress or otherwise elongate the tendons of the ankle excessively - both problems that can cause pain and other unpleasant symptoms.

Heels Rising From Floor

Whether due to poor mobility of the ankles or simple poor squatting habit, the heels rising off the floor as the lifter rises out of the lowest depth of the exercise can result in excessive stress being placed on the tendons of the foot.

Furthermore, this can also cause an overinvolvement of the muscles that make up the calves - also leading to issues relating to the ankle, as it acts as a distal attachment point for the tendons of said muscles.

In order to prevent this, performing dynamic ankle mobility work prior to the workout and otherwise ensuring the heels do not rise by “screwing” the toes into the floor should be sufficient. In certain cases, specialized shoes with an elevated heel may be an appropriate remedy as well.

Knee Valgus

Knee valgus, or inward movement of the knees, is generally meant to be avoided during any portion of the squat’s movement pattern. Not only can it result in hip and knee injuries, but so too can it easily stretch the tissues of the ankle joint into a disadvantageous position.

When knee valgus occurs, the force of the upper body and barbell is translated diagonally into the ankle, of which is already in a state of overpronation or oversupination so as to compensate for one or both of the knees being out of vertical alignment.

This can lead to the ankle rolling even further out of line to the foot, especially if the knee valgus is only occurring on one side of the body - leading to injury, poor performance and even a risk of losing one’s footing in the middle of a squat repetition.

To avoid this, proper mobility work of the quadriceps and hip flexor muscles is in order - as well as ensuring that the feet are pointed at a degree slightly more outward than neutral.

Descending Unevenly

When descending during a squat repetition, allowing one side of the body to move downward before the other can easily lead to the opposite ankle being pulled into a state of overpronation.

This can force the same ankle to enter a state of dorsiflexion prematurely - before the other ankle - and shift the center of the body’s gravity towards the posterior side, placing stress not only on the ankle itself but also the knees as well.

To correct this particular form issue, the exerciser should ensure that the weight is evenly distributed atop the back, as well as that they are descending with both sides in a simultaneous manner.

Uneven and Improper Initial Stance

All lifters are physiologically unique, with their own proportions and ideal range of motion. The initial stance of any squat repetition is no different, and must be modified in accordance with proper form and the lifter’s own needs.

Correcting for this can be difficult from an external perspective, and as such it is best to have the lifter experiment to find their own ideal initial stance by narrowing and widening their foot placement, as well as the angle in which the feet are pointing in relation to the knee joint.

So long as this more comfortable initial stance does not lead to other issues in form, it is entirely permissible within good form practice.

Knees Too Far Past Foot

While some level of anterior knee translation is entirely normal for the squat, overdoing it by bending forward at the knees too early or too far beyond the feet can easily lead to poor transfer of force into the ground, as well as force the ankle joint into a state of excessive dorsiflexion.

A good cue to follow is if the knee and quadriceps are becoming excessively strained from a squat repetition, then the knee is likely too far forward over the foot and should be brought back somewhat.

Other Issues Causing Ankle Pain from Squats

Though form issues are occasionally to blame for ankle pain during or after a set of squats, it is more often a physiological issue - usually mobility - that causes such symptoms.

While these problems are somewhat more time-consuming and difficult to correct than simple changes in squat execution, they are nonetheless just as important and it is unwise to continue squatting without making the succeeding adjustments as well.

Lack of Mobility Work

The most important factor to investigate when experiencing ankle or foot pain is that of mobility.

As was previously mentioned, the numerous tendons that make up the ankle joint are often elongated or placed under stress when a repetition of the squat is performed.

When these tissues are experiencing poor mobility, either as a result of a lack of a warm-up or general neglect of mobility work, they can experience damage due to said stress from squats.

As such, for any lifters experiencing ankle or foot pain from the squat, including several dynamic stretches targeting these areas into their mobility routine is absolutely vital.

Poor Footwear

A frequently overlooked factor when speaking of squats is the type of footwear being used. Lifters may occasionally use footwear that is incompatible with their foot shape, or otherwise entirely incompatible with squats as a whole.

These are often in the form of shoes with excessive or absolutely no arch support, as well as shoes that offer little in the way of heel elevation (which we’ve covered as another important point in this article).

Due to the hundreds of different shoe types and foot shapes, it can be quite difficult for an instructor to pick one out specifically for a single athlete - though there is indeed a type of athletic footwear known as the squat shoe, of which should more than meet the footwear needs of any squat practitioner.

For lifters who cannot feasibly find any compatible shoe to help their ankle pain, purchasing a pair of quality squat shoes should help solve their problem.

Incompatibility Due to Lifestyle or Injuries

Finally, if no current injuries are present yet the lifter is still experiencing ankle pain after changing every aspect of their squat - then it may simply be that the exercise is incompatible with the lifter themselves.

Whether due to a history of injury relating to the ankles or because of lifestyle-driven factors (such as shortened tendons from frequently wearing high heels), the best course of action may be to simply substitute the barbell back squat with an exercise that better fits the physiology of the lifter.

Movements like the leg press, split squat or hack squat all feature different mechanics that do not place as much importance on the ankles as the conventional barbell squat, and can preserve much of the original muscular activation of the latter movement without triggering the same kind of pain.

Mobilization Exercises for Squat Ankle Pain

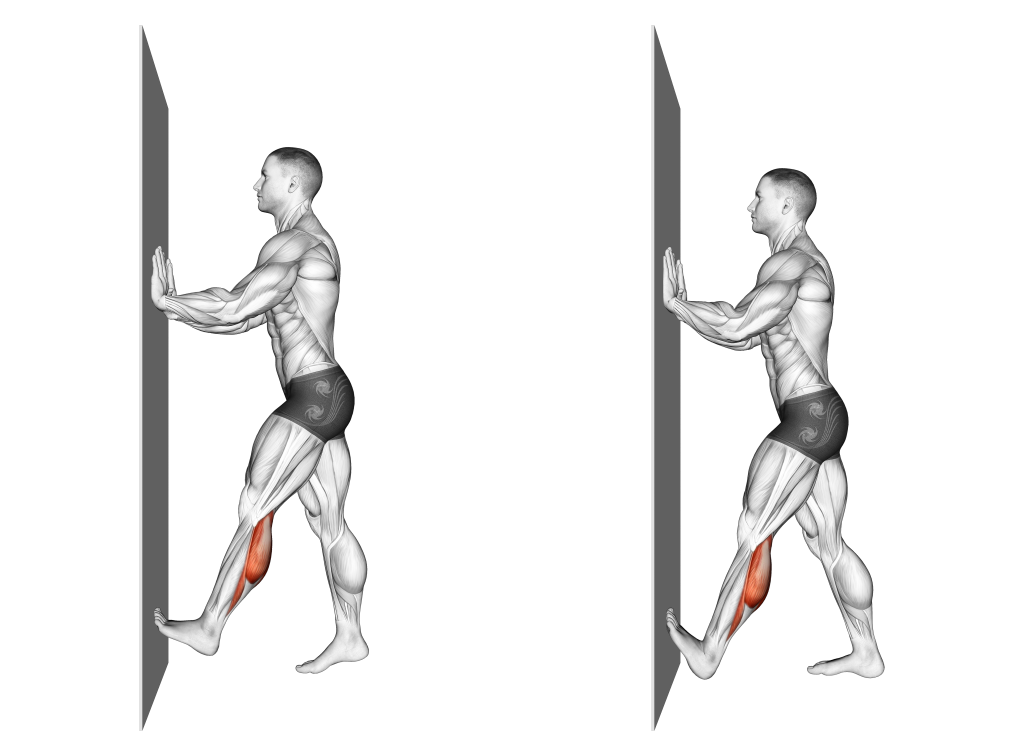

Toe and Heel Points

Perhaps the most simplistic mobility work for the ankles, toe and heel points involve raising the foot off the floor and extending one end (the toes or heels) toward the end of the ankle’s range of motion.

This will elongate either the posterior or anterior tendons crossing the ankle joint near their terminal extension point, improving the mobility of the tissues and the biomechanics of dorsiflexion and plantar flexion.

Ankle Clockwise and Counterclockwise Rotations

In order to improve the ankle’s stability and mobility during a state of pronation or supination, the usage of ankle rotations in both directions can be quite effective.

To do so, simply allow one foot to hang freely while the exerciser is seated, and slowly allow the forefoot to rotate in one direction, only stopping once the ankle is near the end of its range of motion. Then, repeat the action in the opposite direction.

The “ABC” Drill

For a more engaging sort of ankle mobility drill, attempting to draw the alphabet with the toes as the ankle hangs freely in the air can be an excellent way of improving mobility and biomechanical function in all its forms.

Not only will this target all tendons of the ankle in every possible direction, but it can also function as a warm-up due to the volume of movements that are occurring in the area. Performing only one repetition of the drill with each ankle should suffice.

Final Thoughts

While most cases of squat-induced ankle pain are unlikely to be indicative of any serious injury, it is nonetheless a sign that something is wrong with your workout routine and that necessary changes must be made.

And remember, if the pain is accompanied by other symptoms like tingling, swelling or a reduced range of motion, it may be time to talk to a doctor.

References

1. Gomes, João & Neto, Tiago & Vaz, João & Schoenfeld, Brad & Freitas, Sandro. (2020). Is there a relationship between back squat depth, ankle flexibility, and Achilles tendon stiffness?. Sports Biomechanics. 1-14. 10.1080/14763141.2019.1690569.

2. Panoutsakopoulos V, Kotzamanidou MC, Papaiakovou G, Kollias IA. The Ankle Joint Range of Motion and Its Effect on Squat Jump Performance with and without Arm Swing in Adolescent Female Volleyball Players. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Feb 3;6(1):14. doi: 10.3390/jfmk6010014. PMID: 33546291; PMCID: PMC7931004.

3. Halabchi F, Hassabi M. Acute ankle sprain in athletes: Clinical aspects and algorithmic approach. World J Orthop. 2020 Dec 18;11(12):534-558. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i12.534. PMID: 33362991; PMCID: PMC7745493.