Seated Calf Raises: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

For lifters sick of standing for their calf raises, there is a highly convenient but no less effective alternative: the seated calf raise - an exercise used interchangeably with the standing calf raise, but should not be.

Despite the similarity in name and general muscular recruitment, the seated calf raise is in fact distinct from other calf raise exercises, and should be treated as such. In this article, we will explain why that is, and how to take advantage of this otherwise excellent training tool.

To put it in a nutshell, the seated calf raise is an exercise meant to solely target the calf muscles with high volume sets - usually weighted with a dumbbell or through the use of a special rack that goes over the knees, allowing the lifter to stand on their tiptoes and thereby train the calf muscles.

What are Seated Calf Raises?

From a more technical view, the seated calf raise is known to be a single-joint isolation exercise that makes use of free weights or a free-weight-loaded machine to target the muscles of the calves in their entirety.

Unlike the standing calf raise, seated calf raises allow for a greater isolation of the legs in general, and allow lifters who cannot load weight on their spine or torso to otherwise train their calves without worry of injuring themselves.

Who Should do Seated Calf Raises?

Seated calf raises are relatively simple and low impact, and as such are accessible to even total beginners at the gym. So long as the ankles and feet of the lifter are healthy, they can perform a seated calf raise.

In particular, however, runners or powerlifters may see the most benefit from performing the seated calf raise, as it is excellent for building both endurance and strength in a dynamic fashion.

Equipment Needed to do Seated Calf Raises

Seated calf raises will either require a bench and dumbbell, or a seated calf raise machine with a set of weight plates. While there are minute differences between the two exercises, they are largely the same and as such are often grouped beneath the same name.

How to do Seated Calf Raises

In order to perform a repetition of the seated calf raise, the lifter will sit on a bench (or within a seated calf raise machine) and load a moderate amount of weight atop their knees. This may be done by loading the machine with plates, or placing a dumbbell atop the knees, secured by the hands.

Then, ensuring the toes are pointing slightly outwards and forwards, they will roll their foot onto the balls of their feet, stopping once the ankles are nearly in a state of full extension.

Once reaching this point, they will then slowly return their heels to the ground, thereby completing the repetition.

What Muscles do Seated Calf Raises Work?

Seated calf raises are an isolation exercise, and as such will only train one muscle group to any significant capacity; the calf muscles.

The muscles of the calves are responsible for quite a number of different activities and are involved in a plethora of biomechanics, but are especially needed for stabilization when standing upright or walking.

Furthermore, they directly control the ankles and feet, and are responsible for biomechanics like dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

What Part of the Calves Do Seated Calf Raises Focus on?

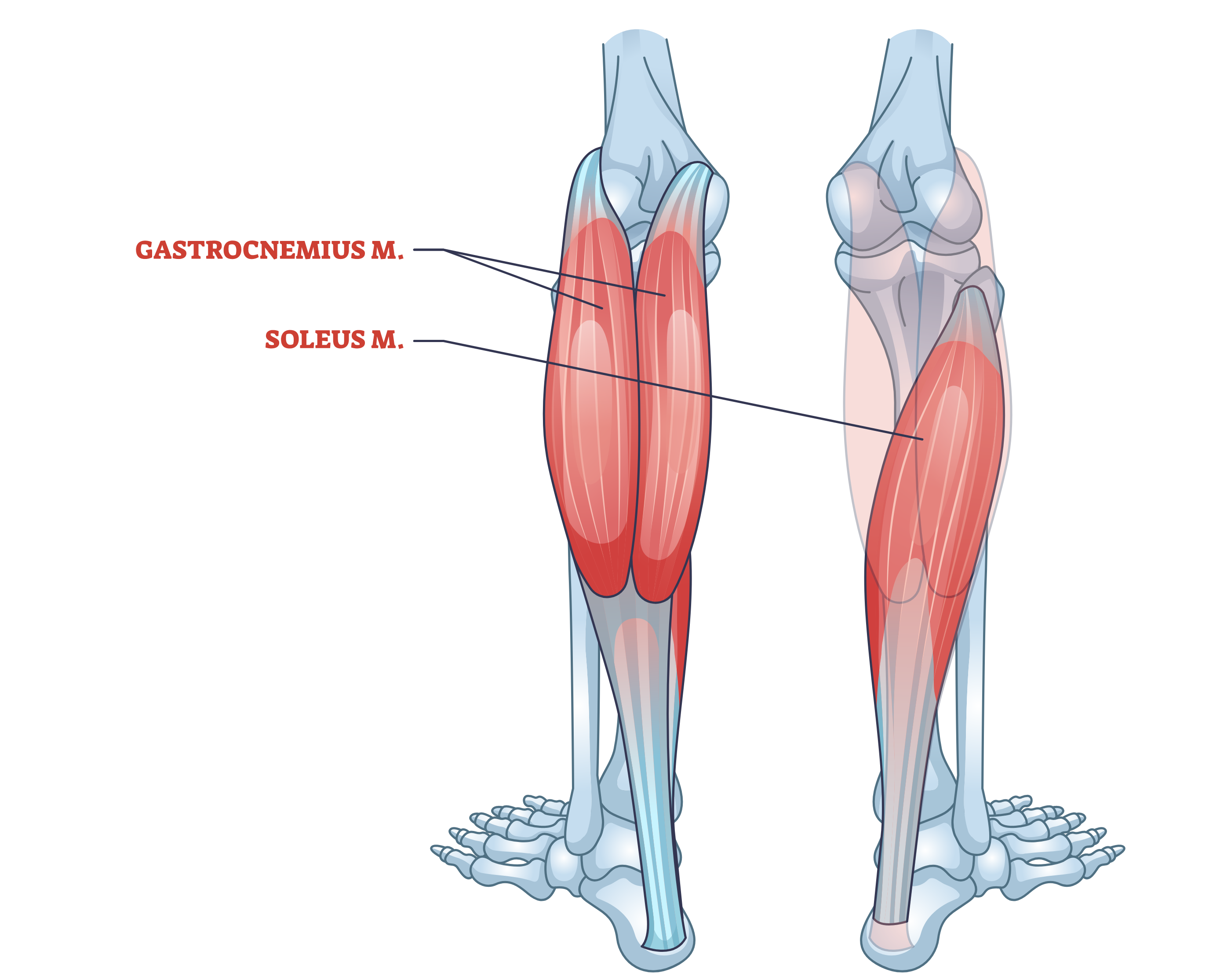

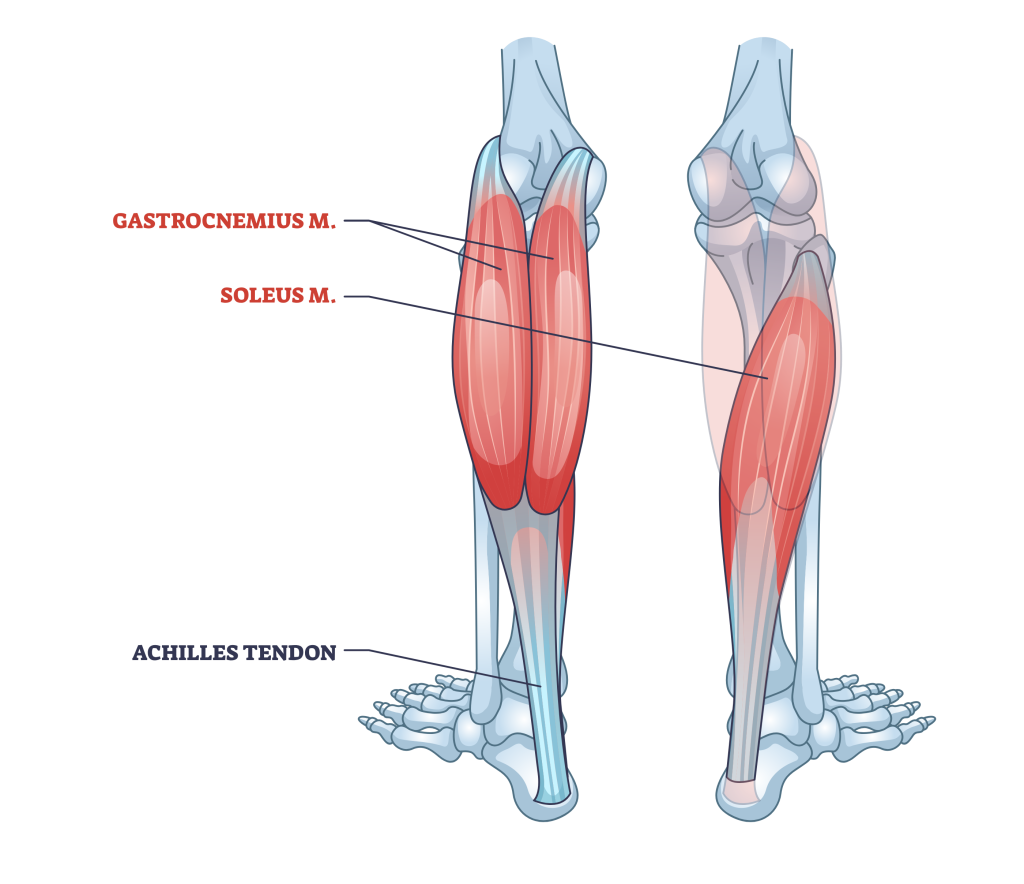

While seated calf raises do indeed work the entirety of the calves to an effective measure, they will place a greater focus on the underlying muscle of the soleus, rather than the two-headed gastrocnemius muscle.

The soleus is a flat skeletal muscle found beneath the gastrocnemius, and is often forgotten due to the fact that it is not plainly visible when an individual flexes their calves. It is used to the greatest extent during plantarflexion of the feet and ankles, and as such is arguably just as important as the gastrocnemius in day-to-day activities or exercise.

The reason why the seated calf raise should not be used as a substitute to the standing calf raise is much the same - it places a greater focus on the inner soleus muscle, and is more useful as a strength or athletic training tool, rather than for building visible muscle mass, as would be the case with other calf raise exercises.

What are the Benefits of Doing Seated Calf Raises?

Apart from strengthening and developing mass in the calf muscles, the seated calf raise is also capable of imparting several benefits that may not be as easily achieved with other exercises - many of such benefits involve strengthening and reinforcing the lower body as a whole.

Excellent Athletic Carryover - Especially for Runners

The muscles of the calves are used in nearly any movement involving the lower body. Knowing this, we can easily reach the conclusion that regularly performing seated calf raises will directly improve an individual’s capacity to perform said movements.

Where this benefit is taken even further, however, is in the case of athletes - particularly runners - of whom require the improved work capacity and strength output that is engendered by seated calf raises and other calf isolation exercises.

Not only will performing these exercises allow runners to run faster or athletes to jump higher, but it will also reduce their risk of sports-related injuries as the muscles and related tissues become stronger as a result of the stresses of resistance training.

Reinforced Achilles Tendon, Ankles, and Feet

Just as how the muscles of the calves are strengthened by performing seated calf raises, so too are the various soft tissues that protect and move the ankles and feet, with none more so than the Achilles tendon.

The Achilles tendon is directly attached to by both the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, and is among one of the most vital bands of connective tissue found anywhere in human physiology, as it allows for actions like walking and standing upright to occur.

As such, one of the most important (and overlooked) benefits of seated calf raises is its capacity to reinforce the achilles tendon and the entire foot-and-ankle structure as a whole, reducing the risk of future injuries and countering the degenerative effects of aging.

Reinforcement and Stabilization of Plantarflexion Mechanics

Because the seated calf raise strengthens the calf muscles and reinforces much of the ankles, it is especially effective at improving plantarflexion of the foot.

Plantarflexion is the movement of the foot downward, and is the direct opposite of dorsiflexion, where the foot will point upwards instead.

It is a biomechanic that is used in nearly any movement involving the legs, and as such can be unstable or suffer from poor range of motion in individuals that do not reinforce it correctly.

Fortunately, seated calf raises will not only ensure that plantarflexion is stable within its range of motion, but also aid in achieving a wider range of plantarflexion of the feet, of which is extremely important for all individuals, regardless of age, injuries or training experience.

Great for Lifters With Sensitive Backs

Though more niche in scope, the seated calf raise is arguably better than the standing calf raise in the way that it does not place any sort of pressure or load on the spine.

Lifters with a history of back or shoulder injuries may wish to avoid the standing calf raise due to the need to either place the weight atop their back or to hold it in their hands - two aspects that are not otherwise present in the seated calf raise.

Common Mistakes of Seated Calf Raises

Though the seated calf raise is relatively simple in its execution, there are nonetheless several common mistakes that even experienced lifters can make, the majority of which can lead to injury or otherwise reduce the effectiveness of the movement as a whole.

Raising the Shins

Throughout the entire exercise, the shins should remain relatively unmoving, with the ankle and foot being the main source of dynamic motion. Ideally, the entire exercise is performed with the ball of the foot staying completely stationary.

Movement of the shin - either by rolling it in a specific direction or “helping” the weight up by extending the knee forward - can take much of the training stimulus away from the calves, instead shifting it towards the quadriceps muscles.

If the lifter is moving their shin so as to move their foot or otherwise shorten the range of motion, it is possible that they possess poor ankle mobility, or that they could be attempting to perform the exercise with too much weight for their calf muscles alone to handle.

In the former case, the addition of ankle and foot mobility work is the best solution. In the latter, reducing the weight and focusing on slow and high-quality repetitions is the better choice.

Using Excessive Weight

Though it may seem obvious, performing seated calf raises with an excessive amount of weight can easily lead to a breakdown in form and eventual development of injuries.

In particular, it is possible to tear the many tendons of the ankles and feet if the lifter is attempting to calf raise more than they are able - a potentially life-altering danger that should be avoided at all costs.

The seated calf raise should be performed with only a moderate amount of weight at most, ideally an amount that allows for at least eight consecutive repetitions performed with correct form.

The calf muscles are clinically established to respond far better to high volume sets, rather than significant amounts of weight, and as such lifters will find that avoiding lifting too much weight will not only help them avoid injuries but also speed the development of their calves.

Performing Repetitions Too Quickly

Just as how using too much weight can put the lifter at risk of injury, so too can rushing through repetitions affect the quality of their training.

Time under tension is a well-established concept in resistance training where - when muscles are contracted against resistance over a lengthy period of time, they will later undergo hypertrophy in a manner that a shorter length of time will not achieve.

Keeping this in mind, we can see how performing seated calf raises too quickly can sabotage a lifter’s development. For the best possible results from the exercise, each repetition should be performed in a slow and controlled manner.

Variations and Alternatives of the Seated Calf Raise

In the event that the lifter finds the seated calf raise to be uncomfortable or ineffective, there are several alternative exercises that feature similar mechanics and also isolate the calf muscles in a similar manner.

1. Leg Press Calf Raise

For a more machine-based training stimulus, lifters may perform the leg press calf raise instead of the seated calf raise.

In terms of range of motion and muscular recruitment, the exercise is identical to the seated calf raise, though the leg press calf raise may be more effective for building mass in the gastrocnemius instead.

Substituting with the leg press calf raise will provide the benefit of a lengthier time under tension, as well as an even lower risk of injury due to the features of a leg press machine.

2. Calf Raise Machine

Another possible alternative to the seated calf raise is a specialized resistance machine known as a calf raise machine.

Unlike a seated calf raise, it is performed in a standing position with a self-stabilizing and vertical angle of resistance, thereby altering the focus of the exercise and featuring a somewhat different movement pattern.

The main benefit to substituting the seated calf raise with the calf raise machine is in its greater capacity for volume and range of motion - both of which may be achieved to a greater degree due to the features of the machine itself.

3. Standing Calf Raises

For lifters wishing to place greater focus on their gastrocnemius, the standing calf raise is the ideal substitute to the seated calf raise.

While it does not feature the same level of soleus recruitment, the standing calf raise makes up for it by allowing for better development of mass and definition in the calves - marking it as the better exercise for bodybuilders or those concerned with the appearance of their calves.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Are Seated Calf Raises Effective?

Yes!

Seated calf raises are among one of the most effective ways of training the calf muscles, especially for athletes or runners who need their calves to be as enduring and strong as possible.

How to Do Seated Calf Raises at Home?

Seated calf raises may be performed at home with the use of a seat and a suitably weighted object to place atop the knees.

While dumbbells or weight plates are the standard, home workout enthusiasts have been known to use water jugs or books in a pinch.

Is There a Difference Between Seated and Standing Calf Raises?

Seated and standing calf raises are primarily differentiated by which part of the calves they focus on. While it is indeed true that they both work the muscles of the calves, they do not train all calf muscles equally.

Standing calf raises will better work the gastrocnemius, of which is the two-headed muscle that is most visible when an individual stands on their toes.

Seated calf raises will instead work the soleus, of which is a flat muscle located beneath the gastrocnemius and is vital for movement of the feet and ankles.

Final Thoughts

To see the best results from seated calf raises, it is best to perform the exercise for 2-3 sets of 8-15 repetitions each, and to ensure that the calves are worked through their entire range of motion in a slow and controlled manner.

The seated calf raise is a solid exercise in nearly all aspects of the term, but it is limited by how it is performed.

Remember that one quality repetition is worth ten poor repetitions, and that proper form should be followed as much as possible.

References

1. Lee, Geoncheol & Kim, Bom & Kim, Jisu & Nam, Inseong & Park, Yoojin & Shin, Woojin & Woo, Sumin & Cha, Seongki. (2014). The Effect of Calf-Raise Exercise on Gastrocnemius Muscle Based on Other Type of Supports. Journal of The Korean Society of Integrative Medicine. 2. 10.15268/ksim.2014.2.1.109.

2. Kobayashi Y, Ueyasu Y, Yamashita Y, Akagi R. Effects of 4 weeks of explosive-type strength training for the plantar flexors on the rate of torque development and postural stability in elderly individuals. Int J Sports Med 37: 470–475, 2016. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1569367.