Romanian Deadlift: Benefits, Muscles Used, and More

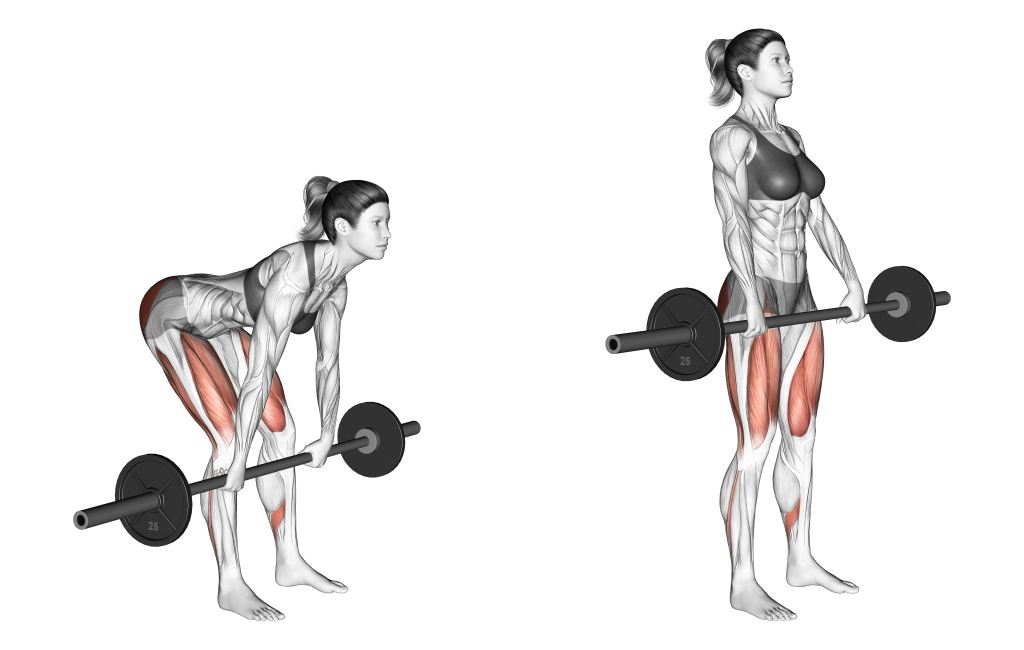

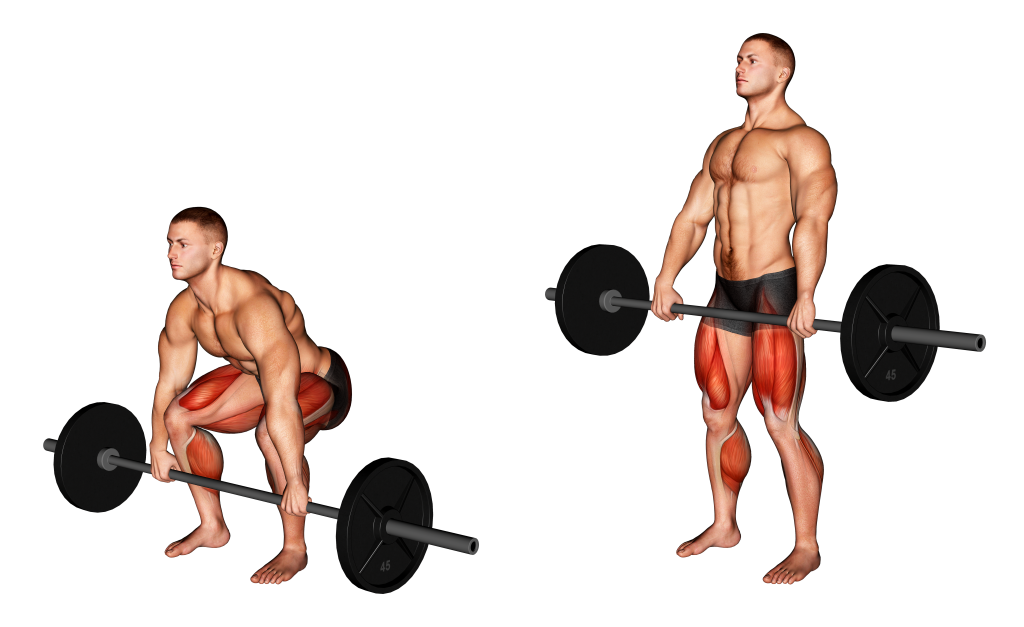

The Romanian deadlift is a closed kinetic chain compound exercise generally performed as part of a legs-focused training session due to its reduced usage of the mid and upper back muscle groups in comparison to other deadlift variations.

In terms of relative exercise intensity, the Romanian deadlift is often performed at a moderate to maximal intensity, depending on the training goals of the exerciser - with a range of anywhere between 7-9 on the Borg's modified rate of perceived exertion scale.

To delve even deeper in the specifics of the Romanian deadlift, we can further classify it into a lower posterior chain training movement due to its specific focus on the hamstrings and glutes, of which are also trained in other variations of the deadlift, though to a lesser degree and in a smaller range of motion than in the Romanian deadlift instead.

How Does the Romanian Deadlift Differ from Other Deadlift Variations?

The romanian deadlift differs greatest from other variations of the deadlift movement by way of its reduced usage of the hips and knees, thereby greatly increasing the activation of the hamstrings and gluteus muscle groups along the posterior chain at the cost of a somewhat reduced training stimulus on the hip flexors and quadriceps.

This is achieved by the exerciser bending further forward during each repetition, extending the lower back further out and pushing the hips backwards in a manner that ensures the exerciser is retaining proper stability while still shifting the percentage distribution to the posterior chain muscle groups instead.

This further extended back and greater gluteus and hamstring muscle group recruitment will also place less strain on the erector spinae muscle group, thereby making the Romanian deadlift a possible alternative to other deadlift variations for individuals with a weakness or history of injury in the lower back.

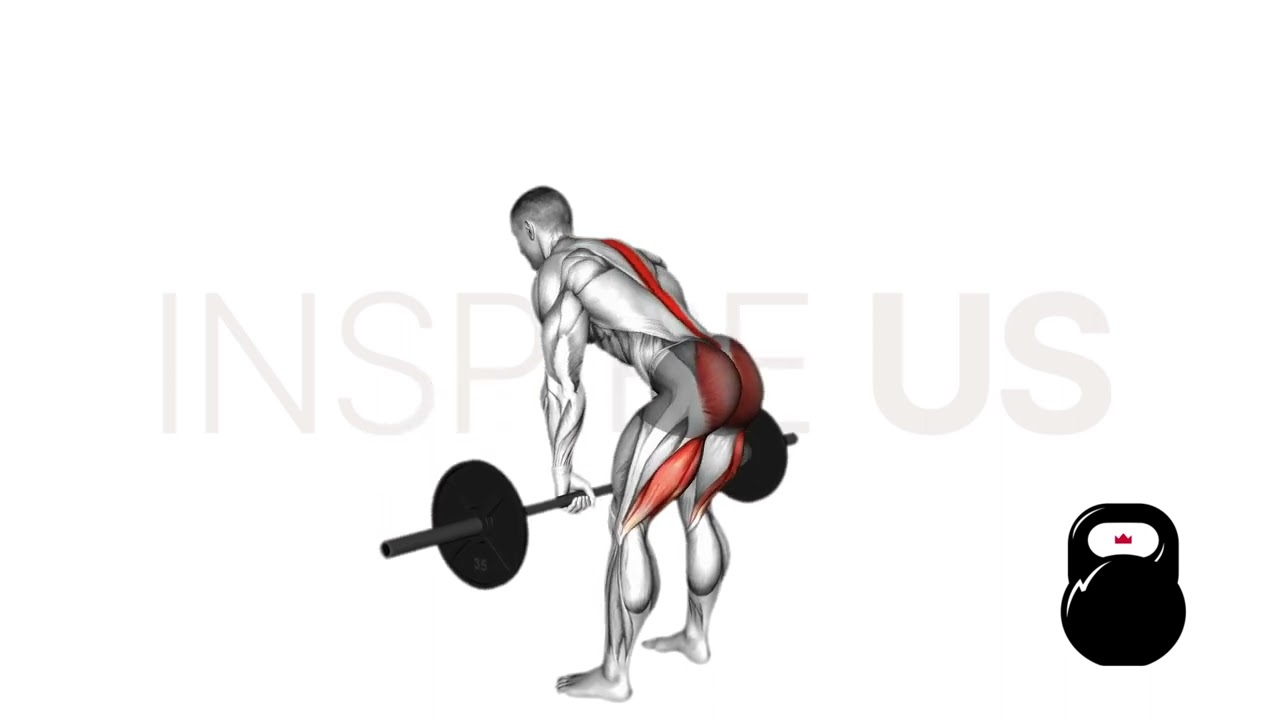

What Muscles are Worked by the Romanian Deadlift?

As a compound movement, the Romanian deadlift is capable of activating a large number of muscle groups at once - all of which contract in varying capacities, with those muscle groups activated to the greatest degree in a dynamic fashion being dubbed the primary movers in accordance with their role during the exercise.

Other muscle groups summarily activated as well (though not in as significant a capacity) are otherwise called the secondary mover muscles, and muscle groups being activated solely in a static manner being referred to as stabilizer muscles.

The Romanian deadlift mainly utilizes every major muscle group in the lower body as a primary mover muscle, with the quadriceps femoris, gluteus muscle group, the various muscles of the hamstrings and the erector spinae all taking a central role during the entirety of the exercise’s movement.

Other muscle groups activated to a less significant degree but nonetheless in a dynamic capacity are the trapezius atop the shoulders, the rhomboids along the upper and mid back as well as the hip flexors, though the latter play a reduced role save for the start and end of each repetition.

In terms of stabilizer muscles, there is the core musculature such as the internal and external obliques or the rectus abdominis, the erector spinae (of which is also a primary mover muscle), the various smaller muscles of the forearms and the deltoids that make up the shoulders.

How to Improve Romanian Deadlift Performance

Apart from regular practice of the exercise, the Romanian deadlift’s performance may be improved by utilizing a proper lower back and hamstring mobility routine that allows the musculature in said areas to remain more stable throughout the Romanian deadlift’s range of motion.

This will not only reduce the risk of soft tissue tears, but also improve the function of synergist muscles in the capacity of stabilization, allowing more energy and force to be directed towards dynamic contraction of the muscles and therefore moving the barbell.

Other ways to improve the exerciser’s performance of the Romanian deadlift is by adding additional isolation work to the exerciser’s training program, with certain exercises such as machine hamstring curls and good mornings having great carry-over to the Romanian deadlift itself.

What are the Benefits of the Romanian Deadlift?

Reduced Lower Back Strain

As the lower back musculature is placed under less stress and the lumbar portion of the spine receives reduced shear force from the angle of resistance during a Romanian deadlift repetition, significantly less stress is placed on the lower back as a whole.

This makes the Romanian deadlift not only a somewhat safer exercise than other deadlift variations in regards to lower back injury, but also one that may be a possible alternative to such variations for individuals with a history of lower back injury - so long as it is approved by a certified physician or physical therapist.

Improved Sports-Specific Athletic Capacity

As a significant number of sports utilize the posterior chain in an endurance and power based capacity, the regular performance of the Romanian deadlift will directly translate to the improvement of certain athleticism related tasks that are useful in a sports-specific way.

The physical ability to perform high jumps, kick with increased strength or propel the body through the water are all reinforced and improved through the performance of the Romanian deadlift, allowing the athlete to do so more powerfully, and for greater lengths of time as muscular and neurological adaptation occurs.

Improved Hip Mobility

As the knees hold a reduced degree of importance during the performance of the Romanian deadlift, it is the hip joint that is utilized to a greater degree; thereby reinforcing the stability of the joint and improving its functional range of motion as the connective tissue is strengthened and otherwise made more flexible as a result of the training stimulus placed upon it.

This works in a two-fold manner, as the Romanian deadlift is also quite difficult to perform without sufficient enough hip mobility, requiring that the exerciser also directly work on their hip mobility via stretching routines and proper warm-up in order to receive the further benefits of the Romanian deadlift.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Romanian Deadlift

Is the Romanian Deadlift Better than the Conventional Deadlift?

The Romanian deadlift is considered to be superior to the conventional deadlift in only a view specific circumstances, with the most common of which being the exerciser requiring greater hamstring and glutes muscle group activation than what the conventional deadlift can provide.

Other situations where the Romanian deadlift may be superior to the conventional deadlift are the exerciser having reduced knee joint range of motion, or if the exerciser wishes to avoid inducing excessive strain and fatigue on the lower back and the erector spinae muscle group.

Is the Romanian Deadlift Safe?

Like any other exercise, the Romanian deadlift is only as safe as the exerciser makes it; with the usage of proper form, the correct amount of weight and appropriate workout programming, the Romanian deadlift can in fact be an extremely safe exercise.

For the most part, issues concerning the safety of the Romanian deadlift revolve around its shifting of pressure and shear force to the kneecaps, whereas said pressure and force would normally be distributed across the lower back instead - presenting a greater, if avoidable, risk of knee injury than in other deadlift variations.

When in doubt, it is an excellent choice for the exerciser to seek out the advice of an athletic coach, as well as the assessment of a medical professional such as a physical therapist or physician.

Can You Do the Romanian Deadlift Without a Barbell?

Though the Romanian deadlift is at its most effective when performed with the use of an olympic barbell or straight barbell, it is entirely possible to instead perform the exercise with the use of a set of dumbbells or kettlebells, of which will present several drawbacks and advantages, such as a reduced maximal load and greater stabilizer muscle recruitment respectively.

Common Mistakes of the Romanian Deadlift

Though the Romanian deadlift is a relatively safe exercise in its own right, many common mistakes primarily to do with certain form cues during its performance can result in a reduction in total training stimulus and thus reduced results from the exercise - or, even worse, injuries that can affect the exerciser’s capacity to even train in the first place.

As such, avoiding the following common mistakes during the performance of the Romanian deadlift are of paramount importance, both to protect the exerciser and to ensure that they are reaping the maximum benefits that they can from the exercise.

Excessive Knee Bend

Usually an issue of too tight hamstrings or a weakened set of hip flexors, excessively bending the knees during a repetition of the Romanian deadlift places much unneeded strain on the patellar joint and its surrounding synergist muscles, potentially resulting in overuse injuries or sprains if a high level of resistance is being utilized.

This may best be avoided through the usage of a proper mobility routine, as well as ensuring that the hips bend in a simultaneous manner with the knees - thereby reducing the strain placed on both joints and eliminating this particular issue.

Internal Rounding of Shoulders

Another common mistake seen during the performance of the romanian deadlift is the exerciser rounding their shoulders and scapula forward as the bar drags the arms away from the torso, thereby placing a more intense level of mechanical stress on the cerebral and thoracic portions of the spinal column, and altering the mechanics of the exercise itself.

In order to present this, the scapula must retain a semi-retracted state, and the exerciser should always seek to keep their latissimus dorsi muscle group engaged throughout the Romanian deadlift exercise, thereby presenting a counter-resistance to the barbell and preventing the shoulders from rotating forward.

Insufficient Knee Bend

Just as the exerciser can bend their knees too far due to improper hip biomechanics, the opposite is also possible; wherein the exerciser’s knees are underutilized and do not share as much of the resistance as other joints involved in the exercise, which in this case would be the hips.

This may result in not only pressure-based injuries of the patellar joint, but also lower back and lumbar spine injuries as the exerciser is forced to bend lower at the hips, placing shear force on the lower back and straining the hip flexors via overextension.

Such an issue is easily remedied by the exerciser learning to pay attention to proper form cues, of which is primarily that the knees must remain somewhat bent throughout the repetition, only locking out at the absolute peak of the repetition, and moving alongside the hips in a simultaneous fashion.

References

1. Martín-Fuentes I, Oliva-Lozano JM, Muyor JM. Electromyographic activity in deadlift exercise and its variants. A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020 Feb 27;15(2):e0229507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229507. PMID: 32107499; PMCID: PMC7046193.

2. Coratella G, Tornatore G, Longo S, Esposito F, Cè E. An Electromyographic Analysis of Romanian, Step-Romanian, and Stiff-Leg Deadlift: Implication for Resistance Training. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Feb 8;19(3):1903. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031903. PMID: 35162922; PMCID: PMC8835508.

3. Delgado, Jose & Drinkwater, Eric & Banyard, Harry & Haff, Guy & Nosaka, Kazunori. (2019). Comparison Between Back Squat, Romanian Deadlift, and Barbell Hip Thrust for Leg and Hip Muscle Activities During Hip Extension. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 33. 1. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003290.