Front Squats: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

Although the term “squat” may conjure up images of a traditional exercise with the barbell loaded onto the back, the front squat is in fact a significant deviation from the ordinary squat, as it places the barbell at the front of the torso and thereby alters the mechanics of the movement itself.

Front squats are distinct among most other squat variations by their comparatively lower risk of injury, as well as their greater emphasis on the quadriceps and gluteal muscles.

Usage of the front squat is most often seen among Olympic weightlifters, athletes and bodybuilders seeking greater development of the aforementioned muscle groups, and is considered to be a highly effective and worthwhile addition into any serious weightlifter's regimen.

However, before incorporating the front squat into your training program, it is important to come to an understanding of what makes it so unique as an exercise.

What is the Front Squat?

In technical terms, the front squat is classified as a multi-joint compound exercise that targets the entirety of the lower body with a significant amount of resistance.

The front squat primarily relies on knee flexion and hip hinging in order to be performed correctly, and is unique in the fact that the deltoids also play a stabilizing role alongside the more traditional lower body stabilizing muscle groups.

In comparison to other squat exercises, front squats will feature a more upright torso and a more vertical angle of resistance - as well as having the feet facing somewhat more forward for greater stability.

Front squats will often be performed with comparatively less weight than the back squat or other squat variations, as the placement of the barbell atop the chest shelf can considerably lower how much the lifter is able to carry. Fortunately, this does not equate to the exercise being of any lesser intensity.

Who Should do Front Squats?

Individuals new to resistance training may wish to try out goblet squats as a more novice-friendly alternative, as front squats are somewhat more difficult than back squats, and as such are considered to be an exercise of at least intermediate level.

Many lifters who cannot comfortably perform back squats or wish to supplement them with a similarly intense movement find the front squat to be the perfect tool for such purposes.

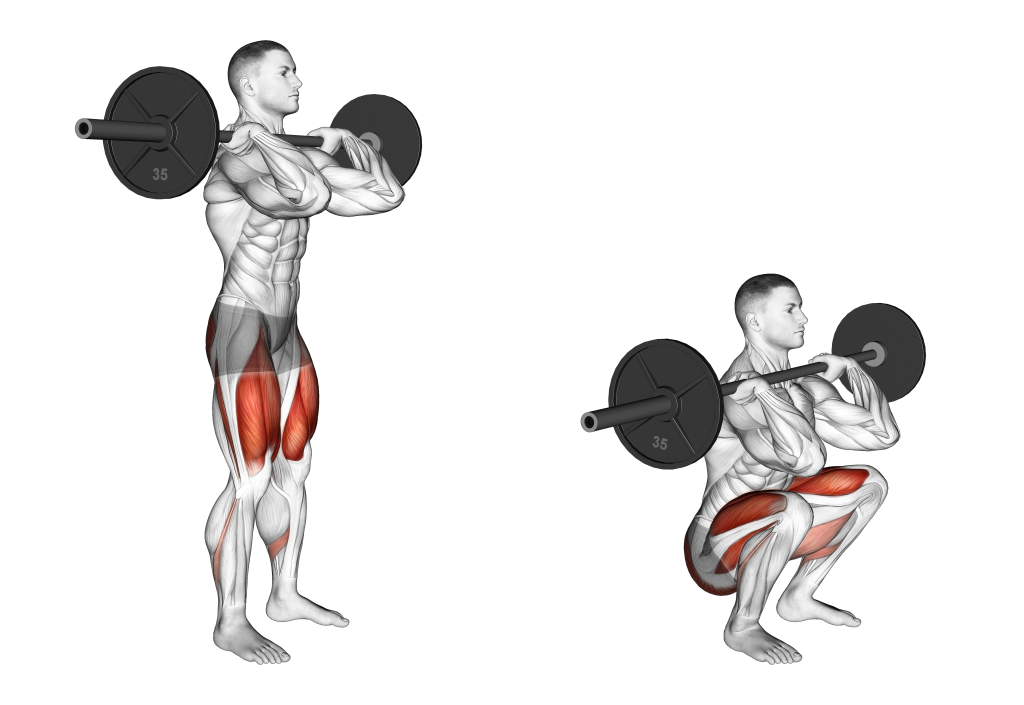

How to do Front Squats

To perform a repetition of the front squat, the lifter will set a loaded barbell atop their chest shelf in the “front rack” position.

This is done by keeping the upper back straight and the chest puffed out, with the elbows pointing forwards and the hands securing the barbell in place as it rests atop the fleshy section of the upper chest, and atop the anterior section of the shoulders.

The bar should be resting quite close to the clavicular bones and neck, but not close enough to cause significant discomfort or pain.

The feet are set a comfortable distance wider than hip-width apart, with the toes pointing forwards or slightly outwards.

Beginning the repetition, the lifter will contract their core and ensure that their entire spine is in a neutral position as they bend at the knees and push their pelvis backwards.

As the hip crease approaches parallel depth with the knees, the lifter will drive through their heels and extend the legs once again - returning themselves to a standing position and thereby completing a repetition of the front squat.

Note that at no point during the exercise should the chest or shoulders bend forwards, and it is important to keep the distribution of load as vertical as possible over the pelvis.

This means keeping the torso upright and the barbell firmly in the front rack position, with the arms and shoulders serving only as a resting place for the bar, therein contributing no dynamic force whatsoever.

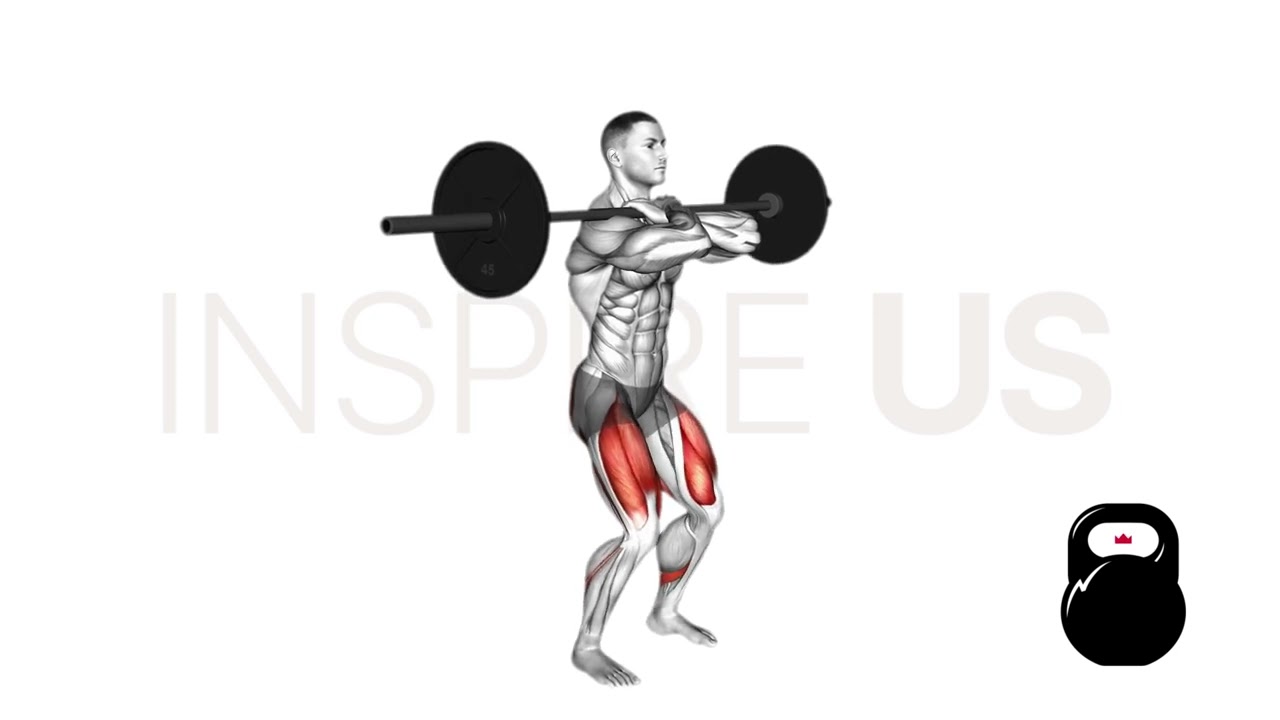

What Muscles are Worked by Front Squats?

Front squats are a compound exercise, meaning that multiple joints are being moved and subsequently multiple muscles are being used as well.

Of course, these muscles are not all worked to the same intensity, and are divided according to the role they play within the exercise, with “primary” and “secondary” mover muscles being those contracted dynamically, and “stabilizer” muscles being those that are worked isometrically.

Primary and Secondary Mover Muscles

During each front squat repetition, it is the muscles of the quadriceps femoris and glutes that act as the main sources of force within the movement.

For secondary mover muscles, the hamstrings and hip adductors are used as well.

Stabilizer Muscles

In terms of isometric contraction, the muscles of the core, erector spinae, calves and deltoids are all worked - each of which help stabilize and control the movement as it is being executed.

What are the Benefits of Doing Front Squats?

Apart from the sort of benefits one would get from all types of resistance training, the front squat is also used as a tool for eliciting the following positive effects;

Great for Quadriceps and Glutes Growth

Although quad and glute development are synonymous with performance of most squat variations, the front squat takes things a step further by maximizing contraction of both muscles - with the quadriceps exhibiting highly intense recruitment during the latter half of the movement, and the glutes the former half.

This is driven by both a reduction in hamstring involvement (of which requires both muscles to work harder in response) as well as the fact that the more vertical angle of resistance requires the quadriceps to concentrically contract to a greater degree in order to counter the resistance of the barbell atop the chest.

Reinforces Spine Neutrality and Other Mechanics

Apart from being excellent at reinforcing the erector spinae muscles - the front squat is also quite useful for reinforcing the many mechanics needed to maintain proper spinal positioning, as well as a number of other vital biomechanics.

Such reinforcement is achieved by both strengthening the muscles responsible for maintaining a neutral spine, as well as helping the lifter fine-tune their own conscious control over their musculature.

Performing the front squat requires arguably even greater mobility and bodily control than its heavier back squat cousin, and as such regularly performing it will help lifters familiarize themselves with mechanics like proper core contraction, c-spine neutrality and keeping their forearms mobile.

Excellent for Maintaining Training Intensity With Less Weight

Because of the barbell’s position atop the torso, lifters will find the amount of weight they can reasonably move to be significantly less than with other heavy compound exercises. This can be a boon for those who have been advised to lay off excessively heavy exercises - or those without access to sufficient equipment

Carryover to Other Quad-Dominant Leg Exercises

Front squats are often used as a supplementary exercise to other movements like it.

Be it the traditional back squat, the leg press or other activities that directly involve the usage of the quadriceps muscles, the front squat will indirectly improve the lifter’s performance therein.

This is most effective when the front squat is trained alongside exercises that place greater emphasis on the posterior chain of muscles, as it will produce a more well-rounded workout and a stronger lower body overall.

Common Front Squat Mistakes

Although we’ve covered the more salient points earlier in this article, there are a few common mistakes that even advanced weightlifters tend to make when performing the front squat.

For the sake of safety and a more effective training session, these mistakes should be corrected as soon as possible.

Rounding the Shoulders or Collapsing the Upper Back

One of the most important form cues during a front squat repetition is proper upper torso curvature.

Allowing the shoulders to round forwards, the chest to collapse or the upper spine to curve will lead to the rest of the body also being pulled out of the proper place - greatly increasing the risk of injury and shifting the balance of the weight itself.

Elbows Pointing Downwards

Wrist, forearm and finger mobility are vital to properly securing the bar in a front rack position.

Because the wrists are bent backwards and the fingers splayed beneath the bar, having the elbows pointing in any direction other than immediately forwards can indicate a deeper issue with the front squat’s stance itself.

Even in cases where the stance is otherwise perfect, having the elbows point downwards can risk the barbell detaching from the top of the chest and falling forwards.

Lifters who have trouble keeping a proper elbow angle should perform wrist mobility work - especially those that focus on wrist extension.

Driving Through the Forefoot

During the front squat, the lifter’s distribution of weight will need to be as optimized as possible so as to avoid injury or poor form adherence. This includes the contact points of the foot, where if the lifter rolls onto the balls of their feet or simply fails to distribute their weight through their heels, the risk of falling over is significant.

Lifters unable to drive through their heels during any squat exercise may be suffering from poor ankle mobility, and as such should seek to perform mobility drills and a warm-up of the ankles prior to attempting the front squat or any other lower body exercise.

Excessively Narrow Stance

While some individuals can get away with a hip-width foot placement during the back squat or hack squat, it is best to form a somewhat wider stance with the front squat, as this will help them maintain their balance and improve glute muscle recruitment as well.

Front Squat Variations and Alternatives

If you don’t have the wrist mobility to safely do a front squat - or if you just want to change up your routine, the following are three good examples of exercises that share many similar characteristics to the front squat with none of its inherent disadvantages.

Goblet Squats

The goblet squat is mechanically similar to the front squat by way of the weight’s placement in relation to the body.

Because it features the lifter gripping a weight between both hands at chest height, the general posture and stance of the two exercises remain much the same, and as such the goblet squat will also train much the same muscles as well.

Dumbbell Front Squats

Dumbbell front squats are simply conventional front squats performed with the use of a pair of dumbbells, rather than a barbell.

This even further reduces the need for training equipment, and can otherwise make the wrist-flexibility demands of the front squat less of a limiting factor for individuals who have trouble with it.

Front Rack Carries

Front rack carries feature a similar barbell position and focus on the lower body, but are instead made more dynamic by having the lifter literally walk around with the barbell atop their chest, rather than performing a squat.

The front rack carry is the ideal alternative to the front squat for athletes and other types of lifters seeking greater functionality in their leg workouts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Are Front Squats Effective?

Very - front squats are great for building up muscle in the quads and glutes, all the while improving your technical proficiency and upper body functionality.

For the best results from front squats, it is important to perform the exercise with proper form and a focus on slow and careful repetitions.

Do Front Squats Build Abs?

Yes.

Front squats utilize the abdominal muscles (among others) in an isometric capacity. While this is unlikely to make your abs more visible, it will indeed build up the endurance and strength of your core.

Why Are Front Squats Safer?

Front squats are not quite safer than other squat exercises per se, but are more so performed with less weight due to the inherent position of the barbell during the exercise.

While this does indeed reduce the amount of strain placed on the body, the front squat is nonetheless just as dangerous an exercise as any other if performed with incorrect form.

In Conclusion

The front squat is one of the most technically useful squat variations out there - but remember that it shouldn’t be the only compound movement in your workouts.

Whether you’re chasing greater athleticism, chiseled quads or general lower body strength, remember to also perform a few supplementary posterior chain exercises alongside the front squat.

If at any point you feel pain or find a certain aspect of the front squat confusing, it is best to consult a professional athletic coach so as to avoid injury and create a more effective workout plan.

References

1. Bird, Stephen & Casey, Sean. (2012). Exploring the Front Squat. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 34. 27-33. 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3182441b7d.

2. Gullett, Jonathan C et al. “A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 23,1 (2009): 284-92. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818546bb