Dumbbell Squat: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

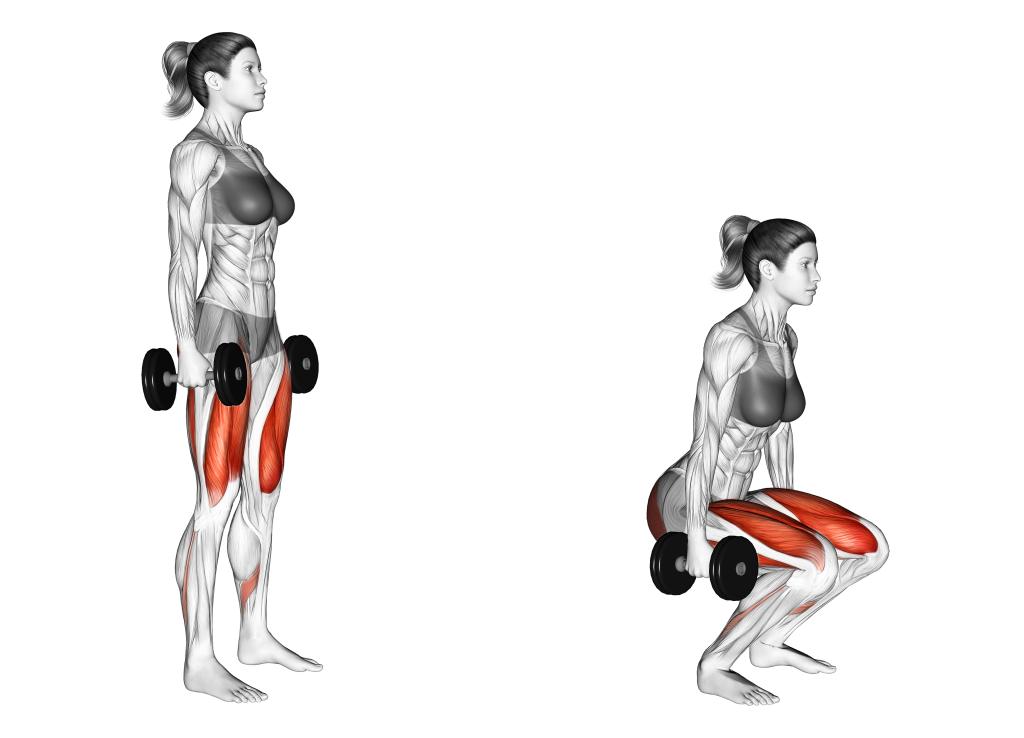

In essence, dumbbell squats are a closed chain free weight compound exercise performed so as to target muscles like the quads, glutes and hamstrings.

Like most other forms of squat, dumbbell squats make marked use of hip and knee flexion, and will involve the lifter lowering themselves from a standing position into a squatting one.

Dumbbell squats are significantly more accessible and novice-friendly than the more traditional barbell back squat. This is both on account of their less complex form and the fact that dumbbell squats are far less likely to result in injury.

How to Do Dumbbell Squats

To perform a repetition of the dumbbell squat, the lifter will begin by first setting their feet approximately shoulder-width apart, toes pointing forwards or slightly outwards and the torso upright with the core braced.

The head should be facing forwards and the chest should be puffed out with no rounding of the upper back present.

Depending on the lifter’s preferences, the dumbbells may be either racked atop the shoulders or simply gripped in both hands at the sides of the hips.

Now in the correct stance, the lifter will push their pelvis backwards and bend at the knees - lowering themselves until the crease of the hips is parallel to the top of the knee.

If holding the dumbbells at the sides, a slightly more hunched forward position of the torso may be needed (in comparison to other squats). Ensure the shoulders do not round forwards and the spine remains neutral.

Once at proper squat depth, the lifter will then drive through their heels and rise back upwards - returning to a standing position and thereby completing the repetition.

What Muscles are Worked by Dumbbell Squats?

Dumbbell squats are a compound movement, meaning that more than a single muscle group is targeted throughout its movement pattern. These muscles are divided according to the role they play within the squat, with “mover” muscles contracting dynamically and “stabilizer” muscles contracting isometrically.

Mover Muscles

In terms of the most intensely worked musculature, dumbbell squats will emphasize the quadriceps above all. In addition to them are the hamstrings and glutes - both of which are also contracted to a significant degree.

Stabilizer Muscles

Dumbbell squats will also isometrically contract the core, erector spinae and (depending on grip style) the forearm musculature.

Unlike the mover muscles, stabilizer muscles do not visibly lengthen or shorten during the exercise. This equates to comparatively less hypertrophy of such musculature, as they are acting solely in a supportive capacity.

What are the Benefits of Doing Dumbbell Squats?

Dumbbell squats are performed so as to achieve the following benefits.

Excellent for Building Lower Body Strength and Mass

The main benefit to performing dumbbell squats is its capacity to develop strength and muscle mass throughout the lower body. The quads, glutes and hamstrings all develop quite effectively with regular practice of dumbbell squats - so long as proper programming and form are followed.

Because dumbbell squats are difficult to load with significant amounts of weight, they tend to gear more towards building mass through volume-driven hypertrophy, rather than directly improving muscular strength through low-volume high-load sets.

Accessible to Novices and Those Without Barbells

Dumbbell squats are significantly less complex than back squats or deadlifts.

This (among other factors) equates to a lower risk of injury and greater accessibility to individuals that haven’t quite mastered the more important heavy lifting cues.

Even for those who are not novices, dumbbell squats also present a highly convenient alternative due to how widespread and space-saving dumbbells can be. Even if no barbell is present, it is likely that the lifter has a dumbbell at home - or can find a set in their hotel gym, if on vacation.

Comparatively Less Pressure on the Spine

Posterior loaded exercises like the barbell back squat can cause vertical pressure to be distributed throughout the spine, potentially leading to compression or injury if poor form is also a factor.

Fortunately, dumbbell squats do not suffer from this issue as much, as they place the load either in the lifter’s hands or along the anterior section of the shoulders. This distributes the weight safely throughout the body and greatly reduces any risk of spinal injury.

Of course, rounding the back or failing to brace the core can still cause back injuries to occur, even with the dumbbell squat. Remember to always be mindful of your entire stance while lifting.

Self-Limiting Resistance

Although not quite a benefit depending on who you ask, the fact that dumbbells become difficult to carry after a certain amount of weight can help mitigate the risk of the lifter moving more weight than they are able.

Conversely, if you are strong enough to lift more weight but find your grip strength limits you - try lifting straps out.

Easily Modified to Meet Training Needs

Dumbbell squats have been modified into so many variations that it becomes difficult to tell what one means when they mention “dumbbell squats”.

Placing the dumbbell at the front of the chest, for example, turns the movement into a goblet squat and better emphasizes the quadriceps. Alternatively, extending them overhead turns the movement into an overhead squat - and so on and so forth.

Because dumbbells themselves are so maneuverable and can be held in a variety of styles, there is almost no end to the ways you can modify the conventional dumbbell squat.

With the right modification, the dumbbell squat can better emphasize certain muscles, create activity-specific training stimulus and even reduce pressure on certain parts of the body.

Common Dumbbell Squat Mistakes

Although the dumbbell squat is considerably more forgiving than other types of squat, avoid the following common mistakes for the best results.

Rounding the Back

The most important mistake to correct is rounding of the back, be it of the lower or upper portion.

Quite a number of different reasons can be causing poor back neutrality, but the most likely is simply that the lifter is unconsciously doing so. The core should be properly braced, the lower back flat and the upper back retracted with the chest pushed out.

Other causes may be the head and neck being misaligned, attempting to lift too much weight or failing to properly hinge at the hips.

If issues with the back rounding are still present after conscious correction, the lifter should stop performing the squat and reassess their execution in order to find the underlying cause.

Failing to Brace the Core

Related to rounding of the back - failing to brace the core or doing so incorrectly can lead to poor power development and a potentially dangerous torso orientation.

Lifters should ensure that their abdominal muscles are braced and that they have “trapped” their breath at the start of the repetition. Exhaling during the descending phase of the movement is entirely fine - if desired. However, the core must nonetheless remain braced despite this.

Those with trouble bracing the core can temporarily make use of lifting belts to help protect them, but this is a temporary solution and it is far better to learn how to properly brace the core instead.

Hanging the Head

Although somewhat more minor than the previous two mistakes, allowing the head to “hang” or extend forwards can draw the upper back and shoulders out of proper alignment.

Apart from the issues related to such problems, hanging the head while lifting can also create pressure along the cervical section of the spine - independent of the shoulders or upper back.

In order to reduce the risk of making this mistake, keep the eyes fixed on a point several feet away, and ensure that the head is not turned or tilted whatsoever. The chin should be raised but not excessively so, and breathing should come easy through the nose or mouth.

“Dive Bombing” or Lowering Too Quickly

Less a stance or form issue and more of an execution one; lifters should avoid rapidly dropping downwards as they perform the dumbbell squat.

This can create excessive pressure on the knees and ankles, as well as sabotage the development of their musculature by shortening their time under tension.

The descent of the dumbbell squat must be performed in a slow and controlled manner, with the lifter coming to a gradual stop as they reach proper depth. If any bouncing or braking at the knees occurs, it is likely the lifter is descending too quickly.

Knee Valgus or Knees Caving In

Much like in any other squat variation, allowing the knees to cave or bend inwards will greatly increase pressure and strain along the joint itself - as well as collapse the lifter’s entire stance, in more extreme cases.

In order to avoid this, the toes should remain pointing forwards or slightly outwards. In addition, the lifter should exercise proper leg abduction at the hip joint as they lower into the deepest part of the movement.

The knees caving inwards could be a sign that the lifter’s foot placement is too wide, that the weight is too heavy or that they are suffering from poor mobility somewhere in their lower body. Each possible cause should be properly assessed prior to returning to full working weight sets.

Alternatives and Variations of the Dumbbell Squat

If the dumbbell squat doesn’t quite fit into your training needs, try the three following alternatives out.

Goblet Squats

Goblet squats are nearly identical to dumbbell squats, only with a single dumbbell held between both hands at chest-height, palms facing each other. This allows for a more vertical orientation to the torso and will further require a wider lower body stance.

Otherwise, goblet squats target much the same musculature as the dumbbell squat to a similar level of intensity.

Dumbbell Deadlifts

For greater emphasis on the posterior chain, lifters may either supplement or substitute the dumbbell squat with dumbbell deadlifts instead.

Dumbbell deadlifts are performed similar to barbell deadlifts where the dumbbells are pulled from the floor up to mid-thigh using significant glute and hamstring power. While this works the quadriceps to a comparatively lesser degree, it also allows for significantly more lower body explosiveness to be built.

In order to get the most comprehensive lower body dumbbell workout, try performing both dumbbell squats and deadlifts within the same training week.

Dumbbell Split Squats

One highly effective unilateral variation of the dumbbell squat comes in the form of the dumbbell split squat.

As one can guess from its name, dumbbell split squats are performed with the lifter in a semi-split stance, one foot being planted forwards and the other behind the body, heel raised. This allows for greater emphasis and focus on one leg at a time, as well as greater quadriceps recruitment.

Split squats are most often used as an alternative to bilateral squats by athletes or individuals who lack access to sufficient weight for challenging both legs simultaneously.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is Squatting With Dumbbells Effective?

Yes! Squatting with dumbbells can be just as effective as squatting with a barbell in the right circumstances. Make sure to pick the right kind of dumbbell squat variation for your needs.

Which Dumbbell Squat Variation is the Best?

Because of how widely the different types of dumbbell squats can vary, there is no one “best” variation.

However, it is best to start with the conventional dumbbell squat or goblet squat, as they form the basis of most other dumbbell squat variations.

Are Dumbbell Squats Better Than Barbell Squats?

In certain aspects - yes.

Dumbbell squats are considerably easier on the spine and back, and are far less likely to result in injury.

A Few More Tips

Dumbbell squats are inherently self-limiting due to the nature of dumbbells, but that doesn’t mean you should rely on this benefit when programming the exercise. Aim to lift somewhere between 75-85% of your barbell squat working weight, if you indeed have one.

In addition, remember that the stance width of the dumbbell squat will depend on the dumbbells used and your manner of gripping them. Larger dumbbells or holding them at the sides will require you to modify your stance accordingly.

References

1 Graham, John F MS, CSCS*D, FNSCA. Exercise Technique: Dumbbell Squat, Dumbbell Split Squat, and Barbell Box Step-up. Strength and Conditioning Journal 33(5):p 76-78, October 2011. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181ebcf12

2 Wu, Hong-Wen, Cheng-Feng Tsai, Kai-Han Liang, and Yi-Wen Chang. "Effect of Loading Devices on Muscle Activation in Squat and Lunge", Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 29, 2 (2020): 200-205, accessed Sep 7, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2018-0182