Dumbbell Split Squat: Muscles Worked and More

In technical classification, we can determine that the dumbbell split squat is a compound closed chain exercise primarily using knee and hip flexion as its principal biomechanical actions.

The dumbbell split squat is most often programmed as either the primary compound movement in less strength-focused programs or as a secondary movement to heavier exercises like the barbell squat, leg press or deadlift.

Apart from being excellent for building the quadriceps muscles, split squats are also occasionally used as a method of developing lower body coordination, as a balance-honing exercise or even as a more back-friendly substitute to conventional squats.

How to Do a Dumbbell Split Squat

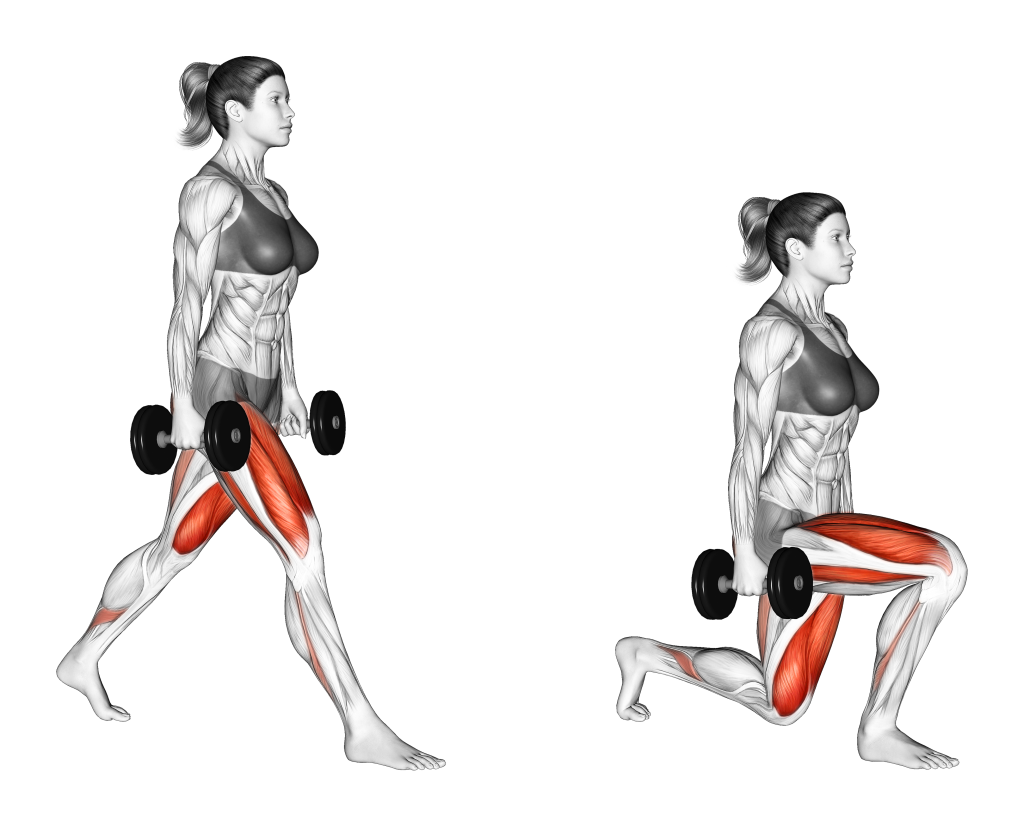

To perform a repetition of the dumbbell split squat, the lifter will begin by gripping a pair of dumbbells at their sides, planting one foot ahead of the body approximately one step away.

Keeping the head facing forwards, the core braced and the torso vertical, the lifter then sinks into a split squat by flexing the hips as they bend at the knees. Avoid leaning too far forwards, as this can create sub-optimal knee tracking and lead to greater irritation of both the ankle and knee joints.

The backward-facing foot should roll off the heel with only the toes touching the ground, helping to facilitate a deeper squat.

Once the foreleg’s thigh is parallel to the floor and the backward-facing leg is nearly touching the ground, the lifter drives through their heel and rises back into their original upright split position.

At this point, the repetition is considered complete. Subsequent repetitions do not require the lifter to step backwards each time. Instead, their feet must remain in place as the lifter simply squats in place.

Don’t forget to repeat the movement with the legs swapped as well.

Sets and Reps Recommendation:

Because dumbbell split squats are not meant to be performed with a significant amount of weight, lifters should aim for a relatively greater amount of volume with each set.

2-4 sets of 10-16 repetitions should suffice for general lower body training.

What Muscles are Worked by Dumbbell Split Squats?

Dumbbell split squats are a compound movement, meaning that multiple muscles are targeted throughout its movement pattern.

To further identify which of these muscles directly benefit from split squats, we will need to classify them according to the role they play.

Mover or mobilizer muscles are those muscle groups that dynamically contract to a significant level of intensity, whereas stabilizer muscles are simply those that contract statically.

Mover Muscles

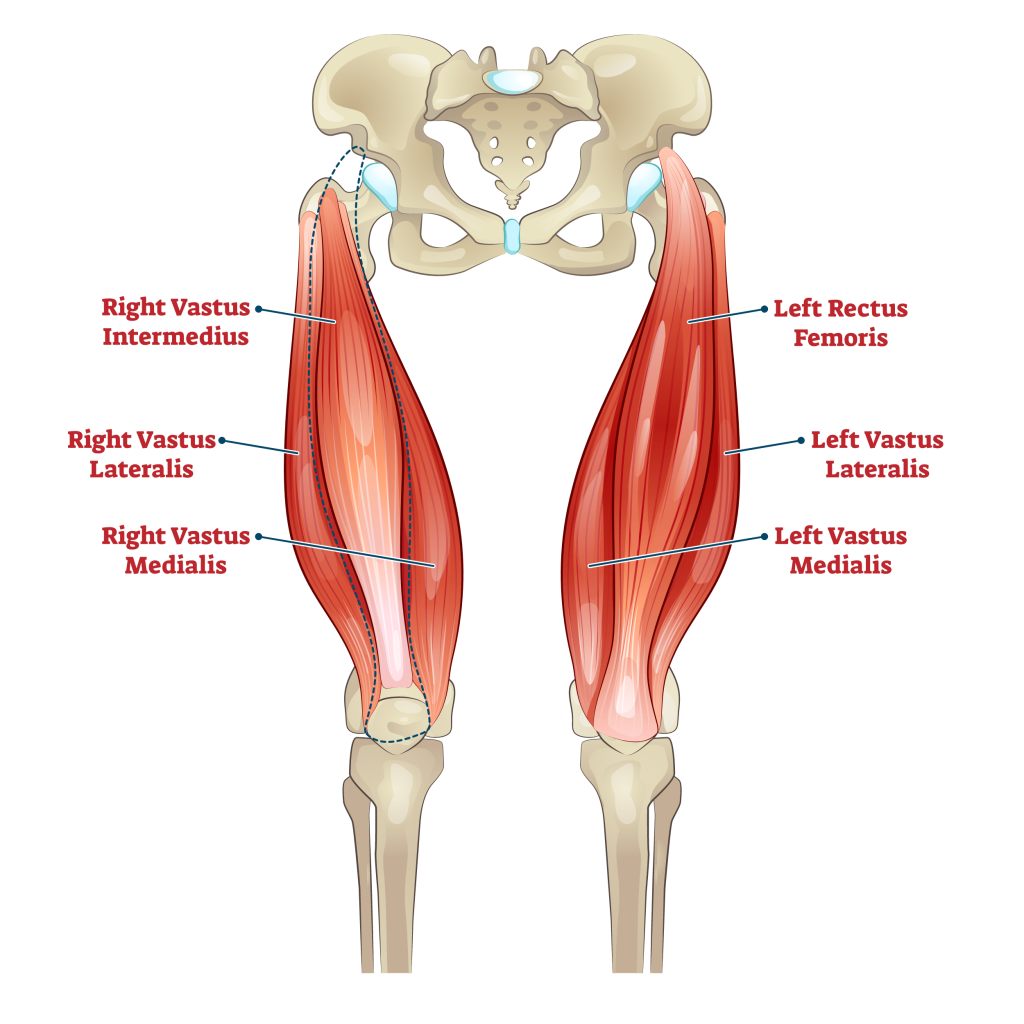

The primary mover muscle of split squats are the quadriceps femoris, as knee flexion and extension are the main mechanics driving the entire movement pattern.

Alongside the quads are the hamstrings and glutes, which act as secondary movers to sustain knee flexion alongside allowing for flexion of the hips.

These three muscle groups act as the main drivers behind a dumbbell split squat, where they are the primary beneficiaries of its training stimulus.

Because of the greater exertion and varying muscle fiber lengths associated with dynamic contraction, it is the mover muscles that receive the most benefit from dumbbell split squats - whereas the stabilizer muscles will only develop to a comparatively miniscule extent.

Stabilizer Muscles

Apart from the mover muscles, the dumbbell split squat also targets the calves, core and forearms to help stabilize the entire movement.

Corrects Lower Body Muscular Imbalances

As is the case with many unilateral exercises, the dumbbell split squat is also capable of correcting muscular imbalances of the quadriceps or hamstrings.

Because each repetition involves one leg acting independently of the other, simply ensuring that both sides are worked to the same volume and intensity should suffice to correct imbalances between the left and right leg muscles.

Common Dumbbell Split Squat Mistakes to Avoid

In order to get the most out of dumbbell split squats, check your form for the following common mistakes.

“Dive Bombing” the Concentric

To reduce strain on the knees and control the risk of excessive lower back flexion, lifters should seek to descend in a slow and balanced manner.

Rapidly dropping downwards can endanger the working knee by having it absorb more force than is necessary, as well as potentially leading to forward curvature of the trunk to compensate for a lack of balance.

Even with an increased risk of strain and injury notwithstanding, performing the dumbbell split squat at a rapid tempo will negate many of its benefits as far as muscular development is concerned.

Essentially, perform the dumbbell split squat in a slow and controlled manner, especially during the initial half of the repetition.

Leaning Trunk Too Far Forwards

Though some level of forward trunk flexion is needed to properly engage the glutes, avoid tilting the trunk too far forwards as this can increase pressure on the working knee.

At most, the torso should only be hinged forward at the hips up to 25 degrees, ensuring that the lower back is nonetheless still neutral despite the trunk leaning forwards.

Knee Valgus

Lifters with difficulty maintaining their balance or poor footwear may find that their working knee begins to cave inwards as they descend - essentially pointing diagonally towards the opposite side.

Like leaning the trunk too far forwards, allowing the knee to bias towards this direction can also increase strain within the joint and potentially lead to injury.

To reduce the risk of the working knee rotating in this direction, aim to keep the toes pointed forwards or slightly outwards, and to focus on descending at the hips, rather than at the knee.

Allowing Rear Leg to Touch the Floor

Whether due to an excessively narrow stance or performing the exercise too rapidly, the rear knee may occasionally make contact with the floor.

Apart from potentially leading to bruising, this is also considered a mistake as it will release tension in the quadriceps and hamstrings. Maintaining consistent tension throughout the lower body’s musculature is vital to ensuring their development.

Perform the dumbbell split squat in a slow and controlled manner, preferably with the feet set far enough apart that the working thigh will still end up parallel to the floor without the rear knee touching the ground.

Dumbbell Split Squat Variations and Alternatives

For a more specific sort of training stimulus (or a more dynamic workout), try the following split squat alternatives out.

Dumbbell Lunges

Lunges can essentially be considered a more active and dynamic twin of the split squat, requiring the lifter to take a step forwards and back with each repetition.

This is in contrast to the split squat, where the lifter remains in place throughout the entire set.

Although both exercises work much the same muscles to similar intensities, lunges will tax the calves to a somewhat greater extent and will generate a greater amount of fatigue with each repetition.

Elevated Split Squats (Front Foot Elevated)

The elevated dumbbell split squat places the forefoot atop a platform higher off the floor, allowing for a larger range of motion and greater contraction of the posterior chain muscles.

Apart from the working leg being higher than with conventional split squats, the elevated variation is much the same - so much so, that it can even be considered a progression exercise for those with a limited selection of weights.

Deficit Split Squats

Deficit split squats are quite similar to elevated split squats, only with both feet elevated, rather than just the working leg.

Much like elevated split squats, performing the exercise in this manner allows for a larger range of motion and greater posterior chain recruitment. However, as an added bonus, the deficit split squat will also allow for less knee strain and help prevent the rear knee from touching the floor.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Do You Use Two Dumbbells for Split Squats?

As much as possible, split squats should be performed with two dumbbells.

Holding only one dumbbell can lead to difficulty maintaining proper balance, and using a goblet grip will require greater awareness of lower back neutrality.

Can You Replace Split Squats With Regular Squats?

Absolutely. Outside of specific training purposes like muscle imbalance correction, regular squats are far better than split squats for training the lower body.

Not only do regular squats allow for greater loading and volume, but they are also considerably easier to balance - reducing the risk of any acute injuries occurring.

What is the Difference Between Split Squats and Lunges?

Split squats are performed stationary, meaning that the feet remain in place throughout the set.

Lunges involve starting and ending from a standing stance with the feet side by side, requiring you to take a large step forwards with each repetition.

References

1. Graham, John F MS, CSCS*D, FNSCA. Exercise Technique: Dumbbell Squat, Dumbbell Split Squat, and Barbell Box Step-up. Strength and Conditioning Journal 33(5):p 76-78, October 2011. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181ebcf12

2. Kipp, Kristof; Kim, Hoon; Wolf, William I.. Muscle Forces During the Squat, Split Squat, and Step-Up Across a Range of External Loads in College-Aged Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 36(2):p 314-323, February 2022. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003688