Deficit Deadlift: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

The deficit deadlift is an excellent strength-building exercise employed by strength athletes and gymgoers alike to develop their deadlift pulling technique.

But, much like the conventional deadlift, performing the deficit deadlift must be performed in the right context and with utmost attention paid to proper form.

In this article, we will discuss what makes the deficit deadlift so beneficial, how to go about performing it correctly and a few common mistakes that you may be making.

What is a Deficit Deadlift?

The deficit deadlift is a closed chain multi-joint resistance exercise classified as both a vertical pull and a hinging movement.

Deficit deadlifts are somewhat more advanced than conventional deadlifts due to the elevation of the lifter’s feet higher off the ground. This effectively increases the exercise’s range of motion and places far greater emphasis on the muscles of the back.

The deficit deadlift is used for not only strength development, but also refining conventional deadlift technique, correcting sticking points or by individuals who do not have access to large-diameter weight plates.

Is the Deficit Deadlift Right for You?

The deficit deadlift is considerably more intense and complex than its conventional counterpart. Lifters should first have a solid grasp of proper deadlift mechanics prior to attempting the deficit deadlift.

In addition, apart from understanding how to deadlift safely, the deficit deadlift will be most beneficial in cases where poor initial pull power is an issue for the lifter. That, or for building stability and technical prowess in the movement through a longer range of motion.

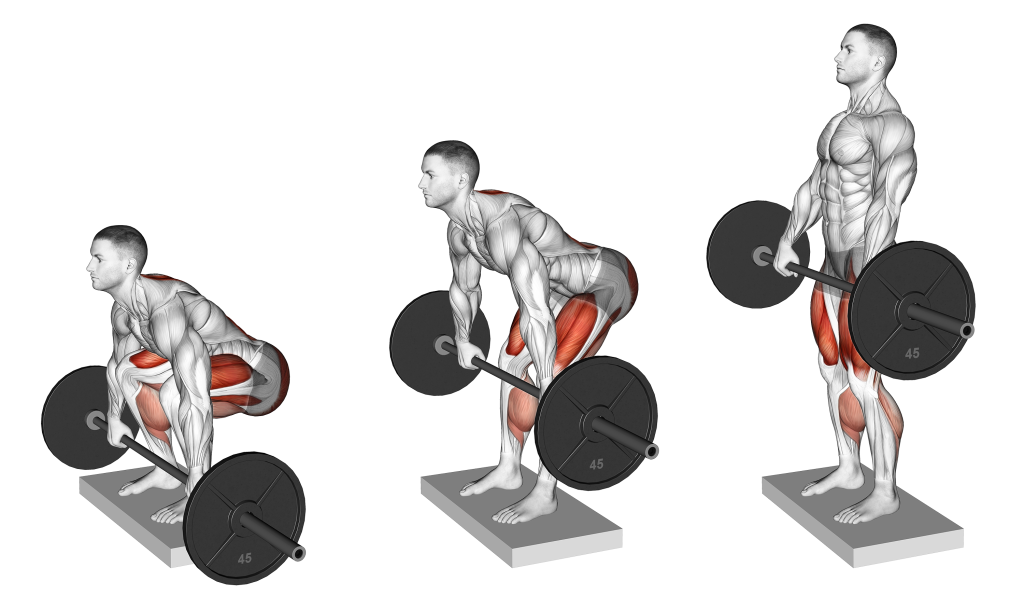

How to Do a Deficit Deadlift

To perform a repetition of the deficit deadlift, the lifter will first begin by standing atop an elevated platform in their preferred deadlift stance (sumo or conventional). A loaded bar should be placed at the front of the platform, beneath the lifter’s feet.

Once in the correct stance, the lifter will lower their hips slightly lower than normal before gripping the bar and aligning their back in a neutral curvature. As always, the core should be braced, the head facing forwards and the chest pushed out prior to beginning the pull.

To do so, the lifter drives through their heels and pulls the bar upwards and against their body - straightening the knees and pelvis as it rises over the shins.

Once standing erect, the repetition may be completed by lowering the bar towards the floor once more.

Make sure to pick a platform that is unlikely to topple or result in your feet slipping as you pull the bar.

While there are indeed platforms specifically made for this purpose, you can also make use of rubber plates or a wooden block as an alternative.

What Muscles are Worked by Deficit Deadlifts?

Deficit deadlifts target much the same muscles as conventional deadlifts, only with greater emphasis on the back muscles due to a more horizontal torso angle.

Mover Muscles

In terms of primary mover muscles, the glutes, hamstrings and quadriceps are all used to a highly intense extent. Supporting them are the secondary mover muscles - of which are the lats, trapezius and erector spinae.

In comparison to traditional deadlifts, deficit deadlifts will feature greater contraction of their secondary mover muscles, as well as a greater level of quadriceps contraction if performing the exercise with a conventional stance.

Stabilizer Muscles

Apart from the mover muscles, the deficit deadlift also isometrically works the erector spinae (again), the muscles of the core and the hip flexors.

Deficit deadlifts will work the hip flexors to a greater extent than with regular deadlifts due to a greater range of motion.

What are the Benefits of Doing Deficit Deadlifts?

Although we’ve mentioned a few benefits inherent to the deficit deadlift, there are quite a few more that make it an excellent exercise for advanced weightlifters.

Excellent for Strengthening Deadlift Pull Power

One of the most common failing points among deadlift performers is right off the floor, where the glutes are engaged and the full weight of the bar is truly suspended in their grip. This is otherwise known as the “pull”, and occurs either due to poor mechanics or weak anterior leg musculature.

The deficit deadlift allows lifters to correct this weakness by setting the initial pull even lower than it would otherwise be - creating a more challenging training stimulus and emphasizing the quadriceps.

Targets the Quadriceps, Back and Stabilizers to a Greater Degree

Although both the traditional and deficit deadlift are excellent for building the lower posterior chain, the latter also excels at targeting the quads and the muscles of the back.

This is a result of the somewhat lower hip position involved, as well as the fact that the lifter will need to bend further forwards to draw the bar off the floor.

Furthermore, the deficit deadlift involves a somewhat longer time under tension with each repetition - equating to more isometric contraction of the stabilizer muscles throughout the set.

Used for Fixing Off-The-Floor Sticking Points and Poor Deadlift Hip Positioning

As mentioned previously, the deficit deadlift is primarily employed to correct poor deadlift pull power- especially in the initial portion of the ROM.

However, this is not quite the same as correcting a sticking point, as a lifter can have a sticking point in the same area despite an explosive upward pull. Deficit deadlifts correct this by forcing the lifter to adopt a somewhat different stance to their usual deadlift positioning - especially in regards to the angle of the hips.

Even if not sure what the specific cause of their sticking point is, using the deficit deadlift can help expose this weakness.

Longer Time Under Tension and Wider Range of Motion

Because the lifter quite literally has to pull the bar from further down, the length in which the muscles are under tension is decidedly longer than with other deadlift variants. This, of course, is based on the wider range of motion that is also a characteristic of deficit deadlifts.

A wider range of motion equates to greater mobility demands of the knees and hips - but will also mean that certain muscle groups are worked to greater lengths. The quadriceps, erector spinae and hip flexors all benefit respectively.

Carryover to Non-Deadlift Exercises (Snatch, Barbell Hack Squat, Box Jumps)

While practicing the deficit deadlift benefits the traditional deadlift the most - seemingly unrelated exercises like barbell snatches, explosive jumps and even the barbell hack squat all benefit as well.

Because the deficit deadlift improves vertical pulling strength and builds power throughout the lower body, any movements involving these physical aspects will also be improved.

In certain athletic disciplines, substituting the conventional deadlift with a deficit deadlift might even be more beneficial to the athlete.

Common Deficit Deadlift Mistakes

Because this is an article about deficit deadlifts, we’ve decided to forego covering mistakes common to deadlifts as a whole. Instead, below, we’ve listed the most common mistakes specific to the deficit deadlift itself.

Keeping the Hips High

The deficit deadlift will require a somewhat lower hip position than most lifters are used to using. Of course, this change in stance is a result of the lower bar position and greater mobility demands overall.

Attempting to perform the deficit deadlift with a high hip position can cause the exercise to turn into more of a back-focused pull than is otherwise necessary. That, or lead to the hips shooting up too early in the movement as the lifter attempts to pull the bar while in a disadvantageous position.

Picking the Wrong Elevation

In the sport of powerlifting, standardized equipment dictates that the traditional deadlift begins approximately 9 inches off the ground.

The deficit deadlift takes this even further - but how far will depend on the lifter’s mobility and proportions.

Generally, the deficit deadlift should be performed with less than 3 inches of distance between the feet and the floor. This, of course, is provided that they can maintain proper spinal curvature and a tight stance while at such an elevation.

Individuals new to the deficit deadlift - or those with poor hip and lower back mobility - should stick to using an elevation of only 1 inch, graduating to 2 inches once more experienced.

Excessive Bracing or Failing to Exhale

Properly bracing and controlling the breath can protect the spine and aid in maximal force output.

However, because the body is compressed to a greater degree during a deficit deadlift, this can lead to a greater risk of losing consciousness or other blood pressure related issues.

If you have a history of hypertension or similar conditions, seek out medical advice prior to attempting the deficit deadlift - or any other deadlift variation, for that matter.

Using the Same Weight as Traditional Deadlifts

One this is certain; the deficit deadlift is considerably more challenging than its traditional cousin.

As such, it is important for lifters to understand that they cannot lift as much weight when performing a deficit deadlift than they would otherwise be able to. Doing so can result in injury and an ineffective training session.

Aim to lift somewhere between 60-70% of your traditional deadlift one-rep max for several repetitions. If you are unsure of what your deadlift 1RM is, see our calculator.

Alternatives to the Deficit Deadlift

If the deficit deadlift is too challenging - or if it's just not meeting your needs - try these three alternatives.

Block Deadlifts

Block deadlifts are the exact opposite to the deficit deadlift. Rather than elevating the lifter, the bar itself is elevated by aligning the plates with a pair of platforms.

This effectively shortens the range of motion, allowing for more weight to be lifted, providing the opportunity to correct mid-range sticking points and creating an overall easier exercise as a whole.

The block deadlift is the right alternative to the deficit deadlift if you have trouble with mid-range traditional deadlift strength or suffer from sticking points near lock-out.

Stiff-Legged Deficit Deadlifts

A more posterior chain focused variation of the deficit deadlift is the stiff-legged deficit deadlift.

While somewhat controversial due to its greater risk of lower back injury - when performed correctly and with moderate weight - the stiff-legged deficit deadlift is nonetheless quite effective at hitting the posterior chain.

If the deficit deadlift emphasizes the quadriceps too much for your liking, try this alternative out.

Rack Pulls

Rack pulls are similar to block deadlifts where the movement begins in a comparatively higher position.

Rather than placing the bar on a pair of platforms though, the rack pull instead has the lifter pulling a barbell as it rests atop the safety bars of a rack.

This emphasizes the back muscles to an even greater degree than the deficit deadlift while still targeting the lower posterior muscles as well.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is the Deficit Deadlift Better Than Regular Deadlifts?

In certain aspects, yes. The deficit deadlift features greater emphasis on the quadriceps and certain portions of the back, but is an overall more challenging and technical exercise.

In addition, you will not be able to lift as much weight when doing deficit deadlifts, making them less effective for competitive strength sports.

Are Deficit Deadlifts Harder?

Yes.

Compared to regular deadlifts, the deficit deadlift has a wider range of motion, less advantageous stance and will tax certain muscles to a greater degree.

Avoid performing deficit deadlifts if you haven’t quite mastered the traditional deadlift just yet.

How Heavy Should My Deficit Deadlift Be?

Your deficit deadlift should be 25-30% lighter than your traditional deadlift working weight would be. While this will vary depending on mobility, proportions and physical strength, subtracting this much weight should be enough to reduce any risk of injury.

Final Thoughts

The deficit deadlift is the ideal tool for correcting deadlift-specific technique issues and boosting pulling strength.

Despite its many benefits, remember that the conventional deadlift is nonetheless still superior in several aspects - the most important of which is reduced lower back strain. To get the best results, focus on the regular deadlift and supplement with the deficit deadlift as needed.

References

1. Lanham, Sarah & Cooper, James & Chrysosferidis, Peter & Szekely, Brian & Langford, Emily & Snarr, Ronald. (2018). Exercise Technique: Deficit Deadlift. Strength and conditioning journal. 1. 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000428.

2. Arandjelovic, Ognjen & Kompf, Justin. (2017). The Sticking Point in the Bench Press, the Squat, and the Deadlift: Similarities and Differences, and Their Significance for Research and Practice. Sports Medicine. 47. 10.1007/s40279-016-0615-9.

3. Farncombe, Lawrence. (AUG 18, 2022) “Powerlifting Essentials”. United Kingdom: Grosvenor House Publishing, 2022. ISBN: 9781803810997, 1803810998