8 Best Types of Deadlift Variations (with Pictures!)

The deadlift is synonymous with heavy vertical pulling and a strong posterior chain - but which deadlift variation is the right one?

There are quite a number of different types of deadlifts to pick from, so much so that trying to pick a specific one can be overwhelming. We’ve chosen to list the most effective ones in this article.

While you’re free to try out any deadlift variation you wish, it is best to start by mastering the fundamentals of the basic conventional deadlift. Once you’ve got the form down, many lifters will often try out the sumo deadlift, Romanian deadlift or stiff-legged deadlift for greater specificity.

What is a Deadlift?

The standard description of a deadlift states that it is a multi-joint full-body movement that is classified as both a vertical pull and a hip hinging exercise.

Deadlifts are most often characterized by being performed with significant amounts of weight and low repetition volume, usually with the lower posterior chain musculature playing a significant role.

The majority of deadlift variations make use of significant hip and knee flexion during the descending phase, and the opposite mechanics during the ascending phase.

Furthermore, nearly all deadlift variants involve a forward tilt of the torso at the hips, as is in line with standard hip hinging mechanics.

A Note on Various Deadlifts Grips

Before diving into the numerous deadlift variations to try, it’s important to make the distinction between a deadlift variation and simply changing what sort of grip is being used.

Because lifters may have trouble keeping hold of a heavy barbell, it is not uncommon for some to switch from the double overhand grip to a mixed grip, a hook grip or even to make use of grip-assisting equipment.

Here's a conventional deadlift with a mixed grip:

Changing the grip does not necessarily make the exercise a variation, even if what muscles are worked changes.

For example, a conventional deadlift performed with a mixed grip (pictured above) is still considered a conventional deadlift, not an entirely separate exercise.

As such, we have not listed the different deadlift grip styles in this article.

Deadlift Variations

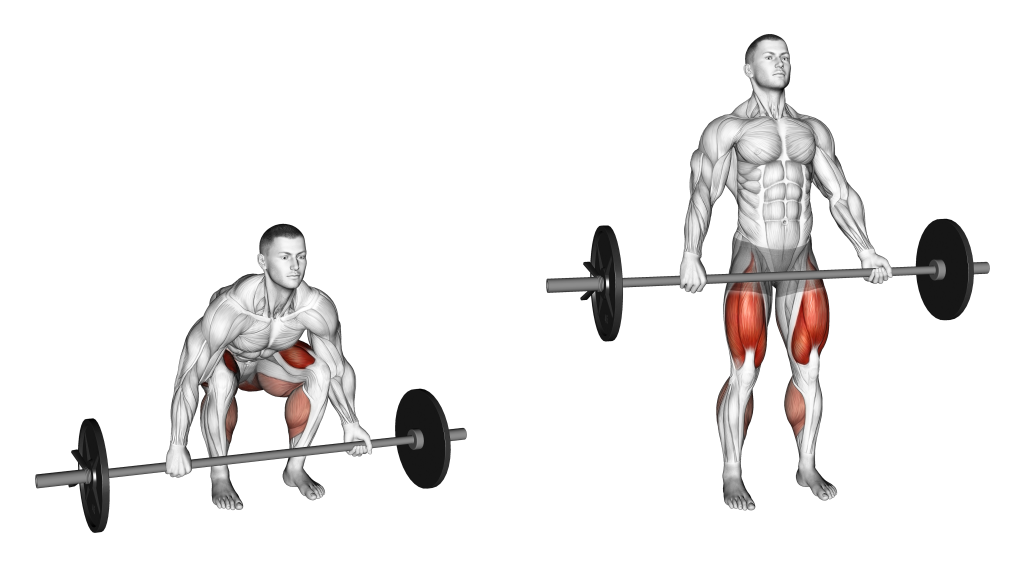

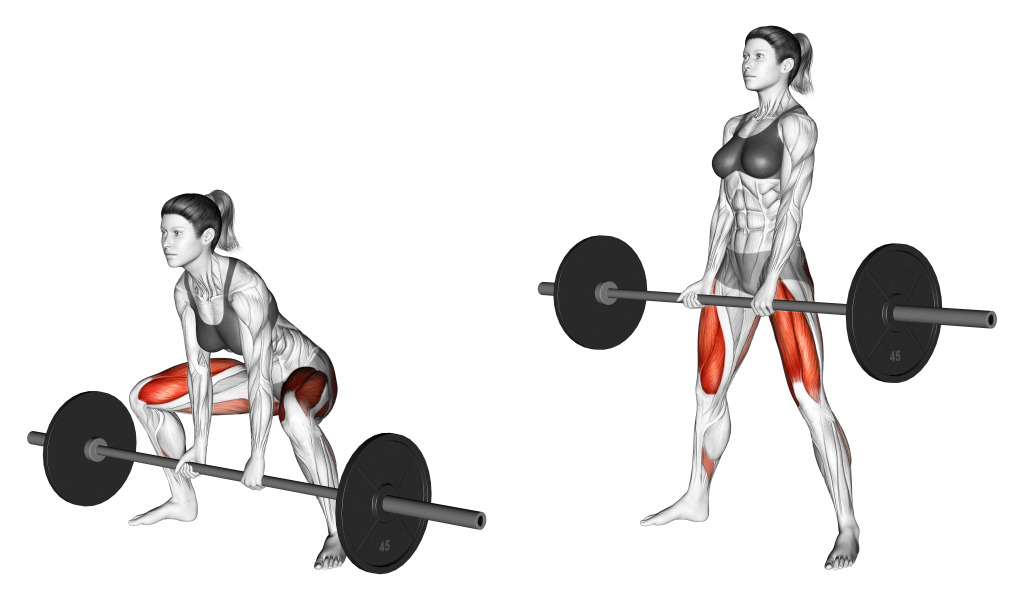

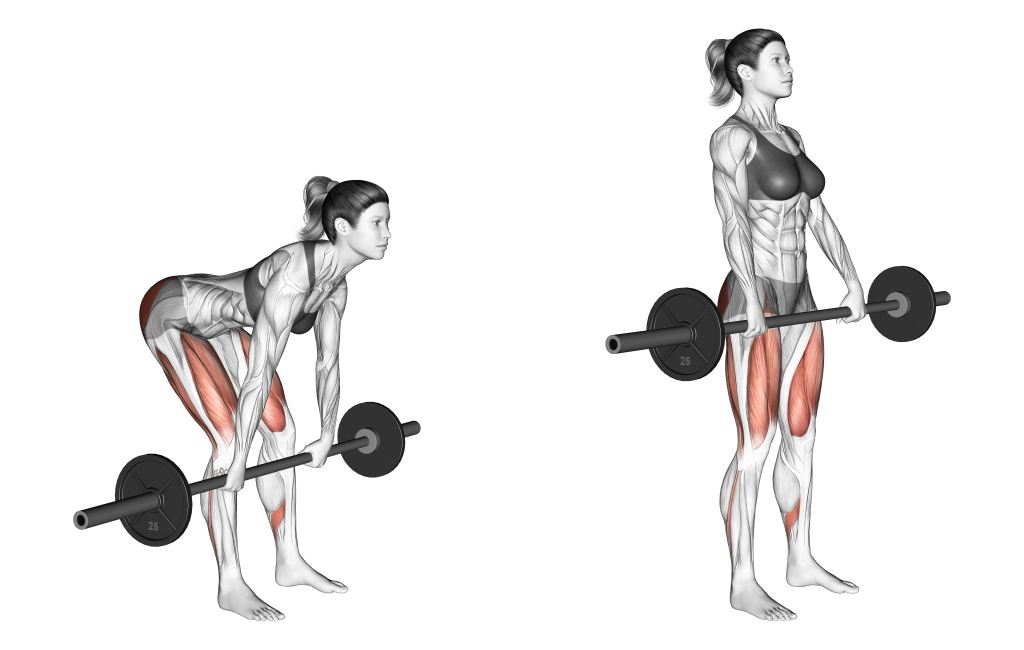

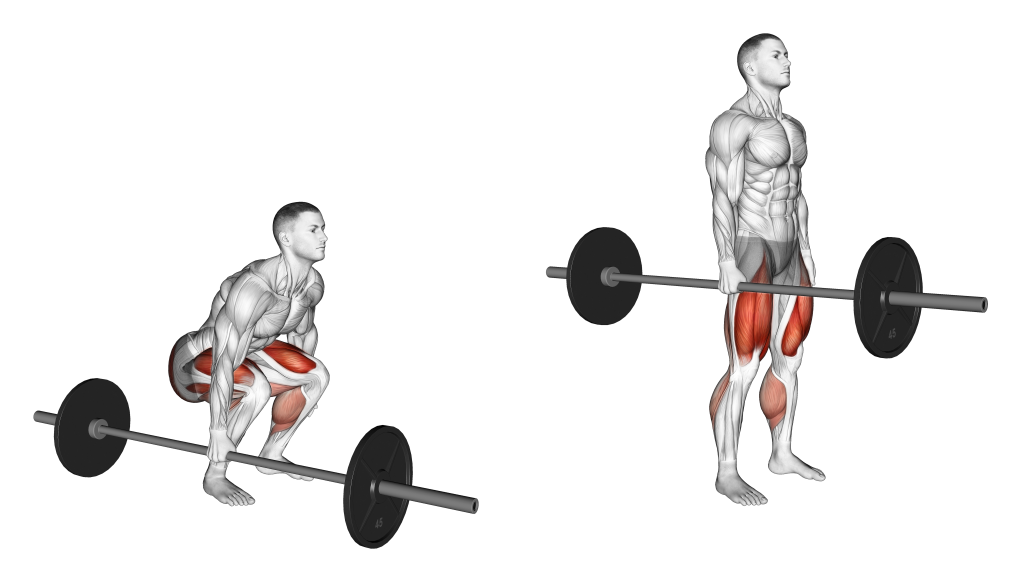

1. Conventional Deadlifts

The “conventional” deadlift is simply the standard deadlift exercise with the feet shoulder-width apart and the hands set outside the knees, often with the use of a straight barbell.

Conventional deadlifts are the baseline deadlift exercise that most lifters should learn prior to attempting more complex variations. Like most other types of deadlift, the conventional deadlift is meant to be performed for low volume and with a significant amount of weight.

Muscles Worked

Conventional deadlifts primarily work the hamstrings and glutes, but will also target the erector spinae and quadriceps as well.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

The conventional deadlift is so widely used because of its capacity to build strength, mass and power in the posterior chain muscles. It is considered a fundamental lift for strength athletes and powerlifters, and teaches much of the basic mechanics needed to perform other exercises of a similar nature.

How-to:

To perform a conventional deadlift, the lifter will set a loaded barbell on the floor several inches away from their shins. The lifter’s feet should be set approximately shoulder-width apart, toes pointing forwards, spine kept in neutral orientation and the core braced.

Squatting downwards and gripping the bar at a width wider than their knees, the lifter will simultaneously drive through their heels, extend their knees and push their pelvis forwards.

This should cause them to pull the barbell explosively upwards, straightening their body as they rise out of the starting position.

Once the body is relatively upright and the barbell is approximately mid-thigh, the repetition is considered to be complete.

2. Sumo Deadlifts

Sumo deadlifts are considered to be the counterpart to the traditional deadlift, as they are quite similar in terms of function and mechanics.

Unlike the conventional variation however, sumo deadlifts use a somewhat wider stance and will instead place the lifter’s arms between their knees. This further recruits the glutes and hamstrings while simultaneously shortening the exercise’s range of motion.

Sumo deadlifts traditionally performed with a barbell, but kettlebells and dumbbells have also been used instead.

Muscles Worked

Sumo deadlifts prioritize the glutes and hamstrings, but will nonetheless also work the quadriceps and other stabilizer muscles as well.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

Posterior chain benefits aside - the sumo deadlift is often used as a substitute to the conventional deadlift for individuals who find the latter to be uncomfortable for their own unique proportions.

In addition, the shorter range of motion that is caused by adopting a sumo stance allows for greater weight to be lifted.

How-to:

To perform a repetition of the sumo deadlift, the lifter will set their feet wider than shoulder-width apart, feet pointed outwards. A loaded barbell should be resting on the floor in front of them.

Squatting downwards by pushing the hips back and bending at the knees, the lifter will set both of their hands a comfortable distance apart in the space between their legs.

Now positioned appropriately, the lifter will drive through their feet and squeeze their glutes - rising out of their sumo stance and into a standing one.

Once the body is relatively standing and upright, the repetition is considered complete.

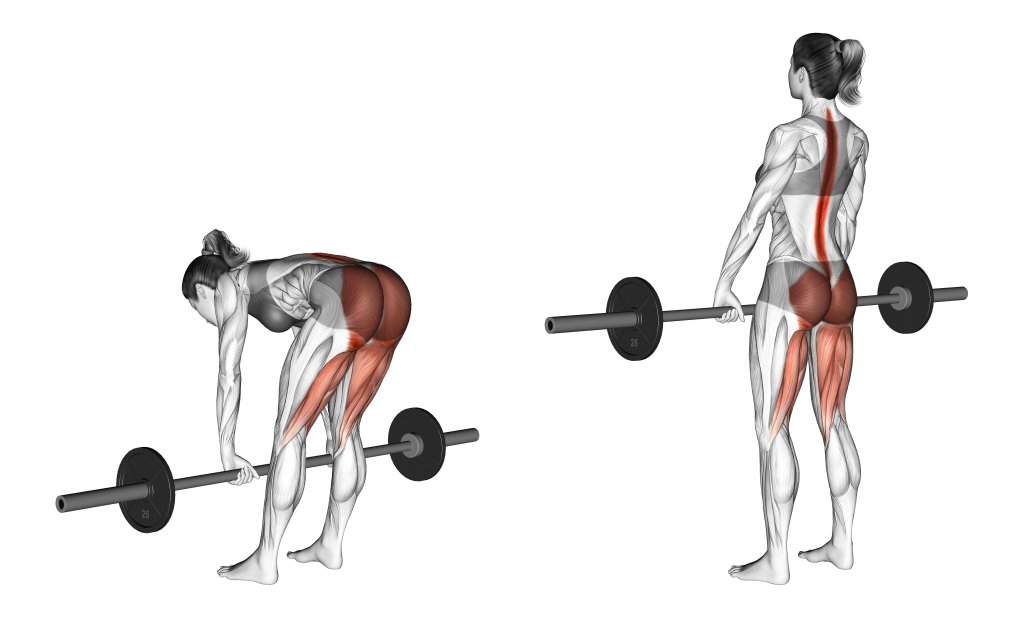

3. Stiff-Legged Deadlifts

The stiff-legged deadlift is a variation of the conventional deadlift where the lifter will bend their knees as little as possible - instead relying on their hamstrings and glutes to bear most of the bar’s weight.

Stiff-legged deadlifts are used as a supplementary exercise for building up the posterior chain in a more isolated and focused manner.

Contrary to what some lifters believe, the stiff-legged deadlift does not necessarily need to be performed with the knees entirely locked out. Instead, some bend at the knees is entirely fine, especially if the lifter suffers from poor hamstring mobility.

Muscles Worked

The stiff-leg deadlift is primarily a hamstring exercise, but will also utilize the glutes, the muscles of the lower back and the erector spinae as well; In a lesser capacity, the quadriceps will also be targeted.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

Apart from being one of the best posterior chain exercises out there, the stiff-legged deadlift is quite useful for reinforcing hip hinging mechanics.

Furthermore, when performed as an accessory exercise to movements like the hack squat or lunge, the lifter can achieve a more comprehensive lower body workout without the need for excessive quadriceps volume.

How-to:

To perform a repetition of the stiff-legged deadlift, the lifter will set their feet hip-width apart with a loaded barbell placed on the floor before them.

Hinging at the hips with as little knee bend as possible, the lifter will reach down and grasp the bar - keeping their spine neutral and core contracted as they do so.

Bar now in hand, the lifter will drive through their feet and push their hips forwards. This should have the effect of drawing them out of the bent-over hinge stance and into an upright one, the barbell somewhere around mid-thigh.

Once the lifter is upright once again, the repetition is considered to be complete.

Further repetitions should have the barbell be drawn off the floor successively.

4. Romanian Deadlifts

Romanian deadlifts are an exercise most often compared to the stiff leg deadlift, as they also involve markedly less use of knee flexion than other deadlift variations.

Unlike the stiff-legged deadlift, the Romanian deadlift begins from the top position and allows for multiple repetitions to be performed without the need to return the bar to the floor each time.

Romanian deadlifts are performed so as to better target the muscles of the posterior chain, and will primarily involve hip hinging as the main mechanic of the movement.

Muscles Worked

Romanian deadlifts emphasize the hamstrings, but will also target the glutes and - to a lesser extent - the quadriceps.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

The Romanian deadlift is noted for having a shorter range of motion and generally more efficient movement pattern in comparison to the stiff-legged deadlift. This allows for more weight to be moved and generally less time spent completing each set.

Furthermore, the fact that the Romanian deadlift does not require the lifter to return the bar to the floor with each repetition equates to a greater time under tension for the posterior chain.

How-to:

To perform a Romanian deadlift, the lifter will set their feet hip-width apart and a loaded barbell on the ground over their feet.

Bracing the core and ensuring the spine is in a neutral orientation, the lifter will then hinge at the hips and grasp the barbell. Driving through their heels, they will then pull the barbell off the floor - pushing their pelvis forwards as the bar reaches the thighs.

From this point, the lifter will reverse the motion and hinge back down until the bar is lowered to approximately calf-height. Once lowered, the repetition is considered complete.

If performing multiple repetitions, the bar does not need to return to the floor, with each repetition starting and ending with the bar at shin level.

5. Single Leg Deadlifts

As the name implies, single legged deadlifts are simply deadlifts performed with one leg raised behind the body. This helps isolate the muscles on one side, and greatly improves the lifter’s capacity to execute a hip hinge.

Single leg deadlifts require some level of balance, technical familiarity and mobility. As such, they are more appropriate for intermediate or advanced weightlifters.

Unlike most other variations, the single leg deadlift is better performed with weights of small size, such as dumbbells or kettlebells.

Muscles Worked

Single leg deadlifts primarily work the glutes and hamstrings, but will also target the quadriceps to a lesser extent.

Greater isometric contraction of the calves, core and other stabilizer muscles is also seen due to the unbalanced stance in which the exercise is performed.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

The primary benefit of the single leg deadlift is its unilateral movement pattern. This not only corrects muscular imbalances, but also improves the lifter’s sense of balance, coordination, and allows for more focus to be given towards working one side of the body at a time.

How-to:

To perform a single leg deadlift, the lifter will stand upright with their feet set hip-width apart, a pair of dumbbells or kettlebells held in their hands (or even a barbell).

Shifting their weight onto one foot, the lifter will hinge at the hips and extend the opposite leg behind them as the torso levers forwards.

If mobility allows, the lifter will follow this hinge until their torso is relatively parallel to the floor and their extended leg is pointing directly backwards.

To complete the repetition, the lifter will reverse the hinge and repeat the same movement with the opposite leg.

6. Trap Bar Deadlifts (Hex Bar Deadlifts)

For lifters seeking a lower risk of injury and greater distribution of load, the trap bar deadlift is their best bet.

Trap (or hex) bar deadlifts are otherwise conventional deadlifts performed with the use of a hexagonal barbell. This allows the lifter to keep their arms at their sides and their wrists in a neutral orientation, rather than all the weight being at the front of the body.

Despite the many benefits of using a trap bar for the deadlift, some reports show that it may be inferior to the conventional barbell deadlift for working the muscles of the posterior chain.

Muscles Worked

Trap bar deadlifts work much the same muscles as the regular deadlift - only with slightly greater emphasis on the quadriceps and less on the posterior chain. In addition, the muscles of the lower back and erector spinae are taxed to a far lesser degree as well.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

The trap bar deadlift is comparatively safer due to its usage of a neutral wrist orientation, placement of the arms at the sides, relatively higher shoulder position and its generally more even distribution of load.

Safety and convenience aside, the hex bar deadlift is also quite effective as an introductory tool to hinge exercises, as its stance requires less hamstring mobility and lower back control.

How-to:

To perform the trap bar deadlift, the lifter will stand within the hexagon of a loaded hex bar, gripping the handles at both sides.

In the starting stance, the lifter’s knees should be bent parallel to the feet, with the hips low and the torso angled upwards. The core should be braced and the spine straight from pelvis to neck.

Once their stance is secure, the lifter will squeeze their glutes and push through their feet, pulling the hex bar off the floor as they rise to a standing position.

Once the knees are locked out and the bar is resting somewhere around mid-thigh, the repetition is considered to be finished.

7. Landmine Deadlifts

The landmine deadlift is yet another deadlift variation performed with the use of a straight barbell and set of weight plates.

Where it differs from other variants is its usage of a landmine attachment. This landmine attachment allows for a unique angle of resistance to be adopted - as well as a sumo-like stance favored by strongman competitors and those who have trouble with proper spine orientation.

Muscles Worked

Landmine deadlifts favor the posterior chain muscles of the glutes and hamstrings, but will also recruit the erector spinae and other back stabilizer muscles as well.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

The landmine deadlift is somewhat more forgiving on the lower back and spine than most other deadlift variants. This is further compounded by the closer and more neutral grip used to hold the end of the barbell - aiding with stabilization and maintaining the correct stance.

Furthermore, because only one end of the barbell is held, the landmine deadlift does not suffer from the same rotational bias that other barbell-based deadlift exercises suffer from. This means that the lifter will not need to work to prevent the barbell rotating on its axis.

How-to:

To perform a landmine deadlift, one end of a barbell should be affixed to a landmine unit, the other loaded with weight plates.

Standing facing the loaded end of the bar, the lifter will set their feet shoulder-width apart and hinge at the hips, bending the knees only enough to allow for mobility. The end of the barbell should be grasped in both hands, fingers interlaced and arms straight across the body.

Now in the correct stance, the lifter will simply extend their hips and rise back into a standing position, drawing the end of the barbell along with them.

Once back in a standing position, the repetition is complete.

8. Suitcase Deadlifts

The suitcase deadlift is an uneven deadlift variation where the weight is placed at the side of the lifter, often with only one arm being used at a time.

Apart from primarily being a unilateral exercise, the suitcase deadlift is quite similar to the trap bar deadlift due to their similarity in stance and load distribution.

Because the suitcase deadlift loads one side of the body at a time, it is considered to be unsuitable for individuals with a history of spinal injury. Alternatively, both sides of the body can be loaded simultaneously, although some benefits are lost in doing so.

Muscles Worked

Suitcase deadlifts work the posterior chain in an intense fashion, while also placing some emphasis on the quadriceps.

Benefits as a Deadlift Variation

The suitcase deadlift is excellent for building functional strength, grip endurance and reinforcing the lifter’s capacity to maintain a neutral torso.

In addition, the position of the weight and the neutral grip used reduces the risk of injury and aids in evenly distributing weight throughout the body - especially if the two-sided version of the suitcase deadlift is used.

How-to:

To perform the suitcase deadlift, the lifter will place a loaded barbell, heavy dumbbell or similar type of equipment at one side, near their shins.

Hinging at the hips and bending at the knees, the lifter will descend into the standard starting deadlift stance as they grip the weights at one side of the body. The other hand may be extended out for balance, if needed.

Stance secure and weight now in hand, the lifter will carefully push their pelvis forwards and drive through both heels - ensuring that their body remains facing forwards and balanced as they do so.

Once in a standing position, the repetition is considered complete.

Which Deadlift Should You Do?

With the sheer number of different types of deadlift out there, deciding on one can be a bit overwhelming. Fortunately, there is a definitive answer for most lifters - pick either the conventional or sumo deadlift as your “main” deadlift variant.

Unless you’re an athlete or an individual with a history of back injury, the sumo deadlift or conventional deadlift will cover most of your needs. Other deadlift variations are simply for achieving a more specific goal, for working on a sticking point, or otherwise changing up your routine.

Don’t forget to prioritize protecting your spine and back above all - and to seek out advice from a coach if you are having trouble with form.

References

1. Coombes, Jeff S.., Burton, Nicola W.., Beckman, Emma M.. ESSA’s Student Manual for Exercise Prescription, Delivery and Adherence- EBook. Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2019. ISBN: 9780729586580, 0729586588