Dead Hangs: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

A static movement somewhere between a stretch and an exercise, the dead hang is an unfortunately underutilized tool in many training programs.

Despite its rather ominous name, dead hangs are in fact entirely safe and as simple a movement as they get - simply hang from a pull-up bar in much the same stance as the pull-up exercise itself.

In this article, we will go over the best way to perform dead hangs, what muscles they work, and the six major benefits of doing them.

What are Dead Hangs?

Dead hangs are a multi-purpose isometric exercise of low intensity - meaning that no joints are moved in a dynamic manner, and much of the muscular involvement of the exercise comes in the form of static contraction.

Although no actual pulling occurs, dead hangs are considered to be a pull exercise because they target much the same muscle groups as other vertical pulling exercises.

While dead hangs are most often used as a stretch or as a warm-up, they also see some use as a pull-up progression exercise or as a tentative rehabilitation tool.

Are Dead Hangs Right for You?

Dead hangs are considered to be technically uncomplicated, but may be difficult for individuals of particularly heavy body weight or those with poor forearm and core endurance.

Despite the physical demands of dead hanging, it is considered to be a novice exercise due to its sheer simplicity - and the fact that it is used as a progression exercise early in bodyweight athlete’s careers.

Rock climbers, calisthenics enthusiasts and individuals with spinal compression discomfort will find that dead hangs are a particularly worthwhile inclusion into their program.

How to do the Dead Hang

To do the dead hang, the exerciser will place both hands shoulder-width apart along a pull-up bar in a pronated grip.

A bench or box may be used if they cannot reach the bar from the floor.

Ensuring that they are freely hanging from the bar, the exerciser will contract their core and glutes so as to steady the lower body and prevent any swinging from occurring.

This position will then be held for as long as needed, ensuring that no movement occurs. Once a sufficient length of time has passed, the dead hang is complete.

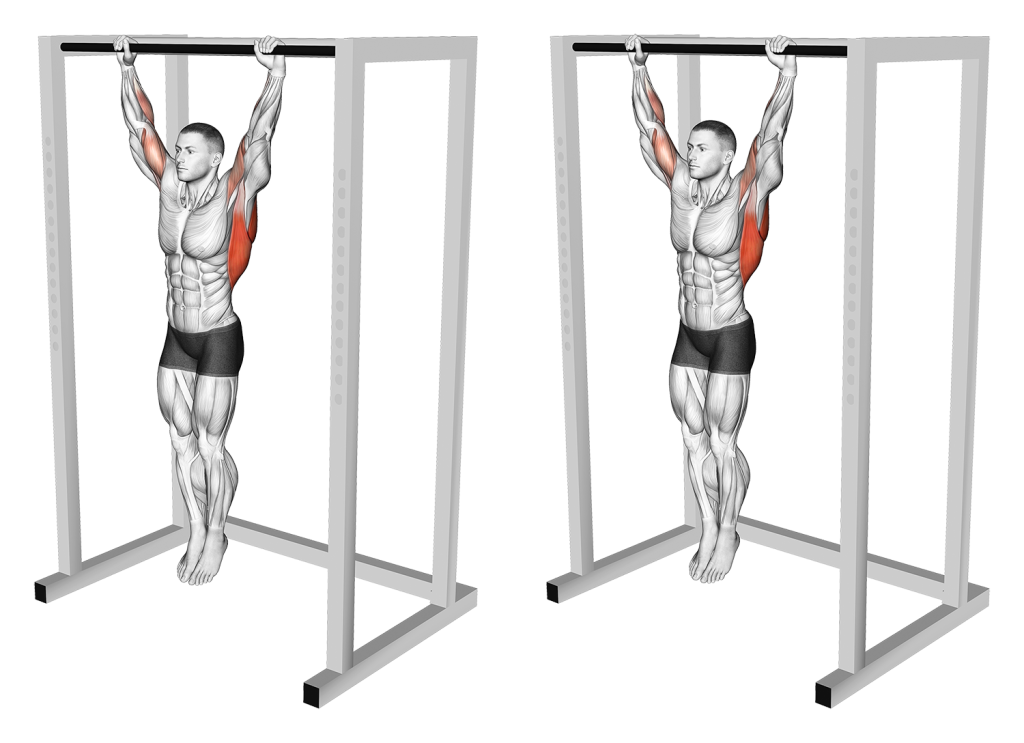

Dead Hang Muscles Worked

Dead hangs do not involve any dynamic contraction - meaning that all muscular recruitment is done in an isometric (static) manner.

The dead hang will work the muscles of the forearms, core and deltoids. In addition, the muscles of the upper back may also play a small supporting role as well.

Major Benefits of Dead Hangs

Because dead hangs are used for more than just stretching or muscular development, listing every single one of their benefits can take some time.

The following are the six most prominent benefits:

1. Decompresses the Spine

Although it is inconsequential in scope, individuals who find that they suffer from the spinal compression effect of squats or similar exercises can use dead hangs to help decompress their spine.

Often, this is due to the incremental loss in height that is associated with load-induced spinal compression - of which is remedied quite quickly with dead hangs.

Note that this is quite different from the medical definition of a compressed spinal disc. If you suffer from such an injury, it is important to speak to a medical professional before trying any rehabilitative exercises.

2. Builds Forearm Endurance

Suspending your entire body’s weight from your hands can be quite challenging for the muscles of the forearms - especially in an unstable and dynamic movement like the pull-up.

Fortunately, dead hangs offer the opportunity to build up the muscular endurance of the forearms without being hampered by other muscle groups, as would be the case with pull-ups.

This makes dead hangs an excellent tool for rock climbers or individuals who find their pull-up performance ended prematurely by fatigued forearms and/or poor grip strength.

3. Reinforcement and Carryover of Pull-Up Mechanics

Although dead hangs aren’t meant to involve active elbow flexion or scapular retraction, they can indeed improve certain mechanical aspects that are vital to performing a pull-up properly.

Individuals who find that their lower body swings excessively during a pull-up - or those with trouble rising out of the starting position - will find that dead hangs directly improve their execution of the pull-up.

4. Strengthens Core Muscles

When performed correctly, dead hanging will directly target the muscles of the core in an intense manner. If combined with certain dynamic core exercises such as the crunch or hanging leg raise, dead hangs will develop stronger and more stable core musculature.

5. Stretches the Upper Body

Dead hangs are occasionally used as a method of stretching the upper body - especially the shoulders, arms and upper back.

Due to its nature as a static stretch, it is better to use dead hangs as a post-workout cool-off tool, rather than one performed prior to a workout session.

6. Acts as Progression to Pull-Ups and Similar Movements

Novice calisthenics athletes who cannot perform a pull-up due to weak stabilizer muscles can utilize dead hangs as a progression exercise.

To do so, it is best to perform multiple sets of dead hangs for increasingly long lengths of time until the athlete can maintain the pull-up position for the length of a full set.

For the most efficient results, we advise combining dead hangs with more dynamic pull-up progression exercises as well.

The Most Common Dead Hang Mistakes

While dead hangs are quite simple to do, the following mistakes may be making them harder than they necessarily need to be.

Hands Too Far Apart

Ideally, dead hangs are performed with the hands set shoulder width apart.

Placing them too far from one another may make maintaining a proper grip on the bar difficult, and cause the muscles of the forearms to fatigue more quickly.

Failing to Contract the Core

In order to perform the dead hang correctly, the lower body should remain stationary with no swinging taking place whatsoever.

This is achieved by contracting the muscles of the core and glutes - of which will help the exerciser remain stationary and reduce the strain placed on the forearms.

Keeping the Arms Bent

Bending the arms during a repetition of dead hangs can cause the biceps to become contracted excessively, leading to premature fatigue in the arms and potentially ending the exercise early.

Alternatives to the Dead Hang

If you can’t hold a dead hang position for long - try out the following alternatives.

Modified Dead Hangs

One of the easiest alternatives to the dead hang is to simply modify it so that it is easier to go from a hanging and standing stance - allowing for less time under tension but also more frequent repetitions of the movement.

To do so, simply place a box or bench below the pull-up bar and return to it as the muscles of the upper body begin to fatigue. This will provide a convenient resting point between repetitions.

Neutral Grip Dead Hangs

For individuals who find the overhand grip of the standard dead hang to be uncomfortable, performing the exercise with a pair of parallel pull-up bars will function in much the same way.

Furthermore, using a neutral grip will allow for a more vertical position of the arms overhead, and reduce any strain on the shoulders that may be present with the standard dead hang.

Assisted Pull-Up Machine Dead Hangs

In cases where the dead hang is too difficult due to the body’s weight, it is entirely fine to perform dead hangs with the help of an assisted pull-up machine.

The machine will provide counter-resistance to the body, reducing how much weight is being suspended by the forearms and therefore making the exercise easier to perform.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How Long Should You Dead Hang For?

Ideally, you should aim to hold the dead hang for 40-60 seconds per set. This should be sufficient for general endurance training or as a stretch, but individuals with particularly enduring musculature can try for far longer if needed.

Can You Do Dead Hangs Everyday?

Unless for non-training purposes, it is best to avoid performing any sort of exercise on a daily basis. Doing so will leave your muscles with little time to recover, leading to irritation and injuries if continued.

Wrapping Up

Dead hangs are an excellent inclusion into practically any training program, cool-off routine or mobility drill - but should not be the sole source of upper body stimulation.

Due to isometric contraction, dead hangs are quite ineffective for building muscle mass (hypertrophy) or otherwise stretching the body in a dynamic manner, as one may need prior to a workout session.

Try pairing dead hangs with movements like arm rotations and dynamic chest stretches for mobility - or with lat pulldowns and crunches for training.

References

1. Stien, Nicolay & Saeterbakken, Atle & Id, Saeterbakken & Hermans, Espen & Vereide, Vegard & Olsen, Elias & Andersen, Vidar. (2019). Comparison of climbing-specific strength and endurance between lead and boulder climbers. PLoS ONE. 14. e0222529. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222529.

2 López-Rivera, Eva & González-Badillo, Juan. (2019). The Effects of a Weighted Dead-Hang training program on Grip Strength and Endurance in Expert climbers with different levels of strength.