Box Squats vs Regular Squats: What's the Difference?

With the different types of squats available to the modern lifter, deciding on which to perform for optimal development can be quite confusing.

Two of the most commonly encountered types of squats are the box squat and the regular squat, both famous for their effectiveness at building lower body strength and size. But when it comes to picking the right exercise for your specific training needs, taking a deep dive into the main differences between the box squat and the regular squat will be needed.

To put it as concisely as possible; the box squat is mechanically similar to the regular squat, only with the range of motion (and momentum) cut short by a raised platform, whereas the regular squat features a full range of motion and may be performed with a smooth transition between both concentric and eccentric phases of the movement.

What are Box Squats?

Box squats are a multi-joint compound free weight exercise frequently encountered in powerlifting and athletic training programs.

It is used either as an accessory compound movement to other squat variations or as a technical tool for improving poor performance during conventional squat execution.

Equipment Used to Box Squat

Box squats will require a barbell, set of weight plates, a rack and some sort of platform that allows for optimal depth to be achieved. Specialized squat blocks, exercise benches or even plyometric boxes may be used.

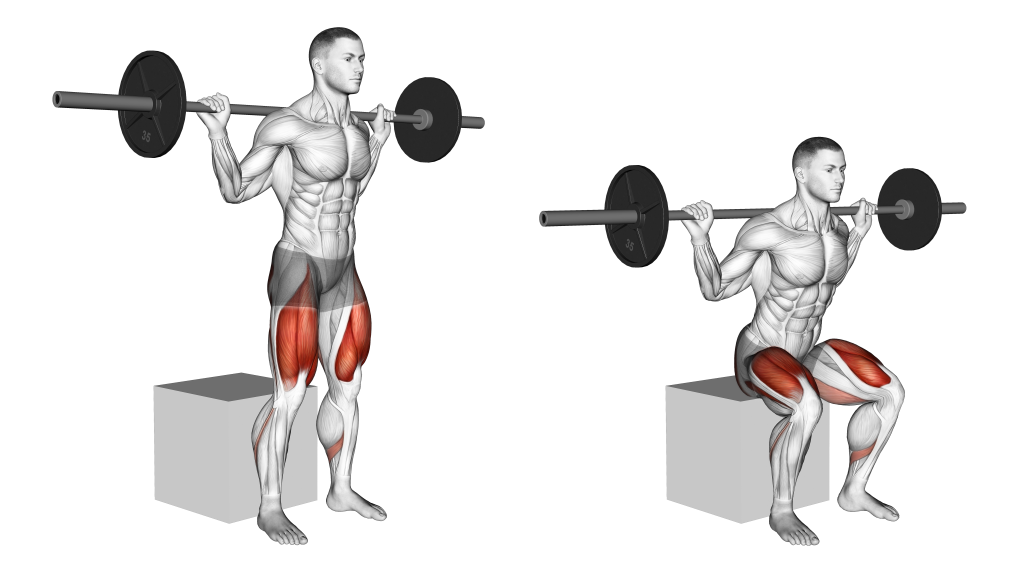

Muscles Worked by a Box Squat

Box squats train much the same muscle groups as regular squats, meaning that the glutes, hamstrings and quadriceps are all used in a dynamic fashion. However, box squats place a greater amount of focus on the posterior chain muscles due to the need for greater explosiveness.

How-to Box Squat

To perform a repetition of the box squat exercise, the lifter will unrack a barbell with their feet set wider than hip-width apart, the box positioned behind them so they may land on it when reaching proper squat depth.

Bending at the hips, the lifter will then lower themselves until they are seated atop the box, thereby arresting their momentum.

Remaining seated for a count, they will then squeeze their glutes and push through their heels, rising once more until their knees have returned to a state of full extension, thereby completing the repetition.

What are Regular Squats?

Regular squats, also known as conventional back squats, are a multi-joint compound exercise widely utilized in nearly every modern weightlifting program.

They are effective at building the muscles of the lower body for nearly every purpose, but are most effective for powerlifters and similar types of strength athletes wishing to maximize the gross strength of the legs.

Equipment Used by a Regular Squat

Regular squats require a barbell and set of weight plates, but the usage of a barbell rack will also be needed as the lifter progresses in weight.

Muscles Worked by Regular Squats

Regular squats will recruit the muscles of the quadriceps, glutes and hamstrings in a dynamic manner, but will produce greater recruitment of the quadriceps in comparison to box squats due to the deeper depth of the former exercise.

How-to "Regular" Squat

To perform a repetition of the regular squat, the lifter will place a loaded barbell atop their trapezius or upper back, setting their feet wider than hip-width apart.

Flexing their core and ensuring the spine is kept in a neutral curvature, they will then bend at the hips and knees simultaneously, lowering themselves until the hips are at least parallel with the knees.

From this position, they will then push through the heels, extending the hips and knees once more until they have returned to a standing position, thereby having completed the repetition.

Similarities of Box Squats and Regular Squats

Before being able to differentiate what makes box squats different from regular squats, it is important to understand the similarities between the two exercises, and to decide on whether either are a suitable exercise at all.

Muscular Recruitment and Biomechanics

Though the actual focus of either exercise will differ, they nonetheless utilize the same biomechanics and will recruit the same muscle groups in a general sense.

This means that the muscles of the posterior chain, core, lower back and quadriceps will be utilized regardless of whether box squats or regular squats are performed - an important factor to consider when programming for either movement.

Furthermore, both box squats and regular squats will utilize hip rotation, knee extension/flexion and ankle movement, albeit in varying degrees. Individuals with poor mobility or injuries in any of these areas should avoid both box squats and regular squats.

Form Cues

While both box squats and regular squats differ in form and depth, they share several form cues that must be adhered to in order to avoid injury.

Setting the feet an appropriate distance apart, bending at the hips and knees simultaneously and ensuring proper spinal curvature are all vitally important parts of performing either exercise.

Equipment Needed

Both the regular and box squat will utilize a barbell, rack and set of weight plates. The sole difference in equipment between the two is that the box squat requires a platform to land on.

Technique Differences of Box Squats and Regular Squats

Though it is obvious that box squats are different from regular squats in terms of actual performance, there are several technical differences that should be kept in mind for optimal execution of either movement.

Knee, Hip, and Upper Body Positioning

Both the box squat and regular squat will use some degree of knee flexion and hip flexion, but the box squat will feature somewhat less usage of the knee joint due to the shorter range of motion made by the box.

This leads to the lifter needing to bend further forward - not only to ensure a balanced position atop the box, but also to allow for greater hip movement to occur, avoiding excessive stress on the knees.

The regular squat, in comparison, uses far greater knee flexion due to the deeper depth and greater recruitment of the quadriceps muscles, though this also means that the hips are used to a lesser degree.

At a larger scale, such hip utilization will allow the torso to remain more upright and vertical, helping the lifter maintain balance and better diffuse weight away from the spinal column.

Maximum Squat Depth

Clearly, the box squat will feature a far higher depth than that of the back squat, as the entire purpose of the box squat is to arrest the descent of the lifter so as to force them to recruit their posterior chain muscles in a certain way.

While this means that the muscles of the glutes and hamstrings are utilized to a far greater degree, it also means that lifters solely relying on the box squat will find themselves performing poorly when performing a conventional squat, as well as that their quadriceps are developing to a lesser degree than the rest of the legs.

In comparison, the regular squat may be performed to a far deeper depth than the box squat, allowing for greater quadriceps muscle recruitment and a more functional form of strength development - though this also equates to greater shear force being placed on the knees.

Stretch Reflex Usage

The stretch reflex in squatting is the capacity for the body to “bounce” when reaching its maximum squat depth due to the muscles of the legs reflexively returning to their original elongation, much like a rubber band.

This primarily occurs in deep-depth squats, and as such is not likely to occur during a box squat set - thereby reducing the usage of momentum, limiting maximum possible weight load and reducing the sports carryover of the box squat.

Box Squats or Regular Squats for Power and Explosiveness

When training for muscular power and explosiveness, picking either the box squat or the regular squat alone may be the wrong answer.

While the box squat is excellent for training the main muscles responsible for lower body explosiveness (the posterior chain), it also features a limited range of motion and is quite poor for functional fitness of any kind.

On the other hand, the regular squat places a greater emphasis on the quadriceps, comparatively being less effective for posterior chain training and therefore less effective for developing power. Nonetheless, the regular squat is still arguably one of the best exercises for building power in the lower body, albeit due to its effectiveness at simply strengthening the muscles therein.

As such, both the box squat and regular squat feature advantages and disadvantages when used for developing explosiveness and power, and the ideal solution is to in fact perform both exercises, with the regular squat used as a primary compound movement and the box squat as an accessory movement for greater posterior chain training.

Box Squats or Regular Squats for Muscle Mass and Raw Strength

When training for pure mass and strength, unless the lifter has a prominent posterior chain muscular imbalance, it is best to stick with regular squats.

Initiating gross strength adaptations and muscular hypertrophy is best achieved through two forms of stimulus:

- Time under tension

- Full dynamic contraction of a skeletal muscle

While the box squat does indeed feature both of these to some extent, it is vastly outclassed by the regular squat simply due to the fuller range of motion featured in the latter squat variation.

As such, if simple muscle mass or stronger legs is the lifter’s goal (and they have no specific need for technical work that may require the box squat), then the regular squat is a better choice.

Use Cases of Box Squats and Regular Squats

Though we’ve established the training and technique differences of box squats and regular squats, there are specific use cases where only one exercise may be the only suitable choice, either due to safety risks or the need to achieve a more technical goal.

For Injured Athletes

Athletes or physical rehabilitation patients with poor mobility or unstable lower body joints may opt to perform the box squat, rather than the regular squat.

The reasoning behind such a substitution lies in the usage of a box itself, as it can provide support if the lifter is unable to continue the set, as well as helps limit the depth to which the exerciser can squat, helping them avoid aggravating their injuries.

This is particularly useful for lifters with poor quadriceps function or knees that are particularly susceptible to damage from shear force, as the box squat helps provide support or otherwise protects these areas better than a regular squat will.

Of course, before including any sort of exercise into your rehabilitation routine, it is best to first consult your physician. The box squat is nonetheless still an intense compound exercise, and may make certain types of injuries even worse.

For Novice Lifters

Novice lifters who are unfamiliar or unable to perform a full squat may wish to instead opt for a box squat, of which should both be easier and less dangerous in the short term.

So long as they do not rely on the box squat for an extended number of training sessions, it can serve quite well as an introduction to squat exercise variations in general, especially for novice lifters who have yet to fully master squatting to a parallel depth.

For Sports Specificity and Carryover

Though both the box squat and regular squat are effective at building the lower body in their own way, it is the conventional or “regular” squat that is deemed to be far better for sports specificity and carryover.

This is a simple result of the fact that the regular squat better replicates more natural movement patterns than the box squat does, especially for powerlifters or strength athletes that will be performing the regular squat in their competition exercises.

Athletes deciding on which exercise to use should keep in mind that the box squat is not without its own merits however, and that it should also be included alongside the regular squat for a more well-rounded training stimulus.

For Conventional Squat Technique

For lifters with poor regular squat technique, there are two approaches.

If their technique suffers from generally bad form adherence or instability, then it is best to perform regular squats so as to better overcome their more glaring issues with squat technique.

On the other hand, if their conventional squat technique suffers from more technical issues like sticking points, poor lockout, knee valgus or failure to correctly recruit the posterior chain; practicing with the box squat can provide more efficient technique work than attempting to correct these issues with the regular squat.

Final Thoughts

Deciding on either box squats or regular squats comes down to the specific needs of your training program, be it targeting specific muscles, overcoming blocks in your training or simply creating a more athletic workout.

Once you’ve identified what you need and which exercise to reach it with, remember to program the exercise appropriately, and to ensure that proper form is followed in all aspects.

If you find that your chosen exercise is uncomfortable or not to your liking - don’t worry, as your choices are not solely constrained to box squats or back squats. Movements like the leg press, hack squat or pin squats can meet much the same needs as well.

References

1. McBride, Jeffrey & Skinner, Jared & Schafer, Patrick & Haines, Tracie & Kirby, Tyler J. (2010). Comparison of Kinetic Variables and Muscle Activity During a Squat vs. a Box Squat. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 24. 3195-9. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f6399a.

2. Swinton, Paul Alan, Ray Lloyd, Justin W. L. Keogh, Ioannis Agouris and Arthur D Stewart. “A Biomechanical Comparison of the Traditional Squat, Powerlifting Squat, and Box Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26 (2012): 1805–1816.