Belts For Deadlifts: Purpose, Benefits, and More

To put it plainly; belts are not needed when you deadlift, but can be incredibly helpful for maximizing total tonnage, protecting your back from injury and helping maintain intra-abdominal pressure.

These belts can vary according to their material, locking mechanism, actual dimensions and intended usage in sports.

What are Weightlifting Belts?

Before getting into the finer details of weightlifting belts, we should first establish what a weightlifting belt even is.

Lifting belts are a form of resistance training accessory equipment meant to wrap around the abdomen - where they provide a solid surface to brace against for the core and help prevent rounding of the lower back through rigidity and tension.

Weightlifting belts are employed in nearly all forms of resistance training, regardless of athletic discipline or athlete characteristic.

Although their benefits as far as safety and strength are widely accepted, not all lifters should use a lifting belt, and not all exercises are compatible with the belt’s functions.

Are There Different Kinds of Deadlift Belts?

Apart from brand, the majority of weightlifting belts are differentiated according to their inherent locking mechanism.

The specific mechanism used by a belt can affect the level of tension or tightness the belt is capable of outputting, as well as the overall durability, adjustability and the weight of the belt itself.

Prong Belts

Prong belts are characterized by their usage of one or two metal prongs inserted into small holes at fixed points along the belt, allowing for rapid and convenient adjustment but limiting the precision of said adjustability.

Prong belts supposedly offer less pressure across the abdomen due to the fixed levels of adjustment they offer, and the fact that the belt can flex or bend around the prongs if made of poor quality materials.

Nonetheless, prong belts remain a favorite among lifters that tend to perform multiple different exercises requiring a weight belt - or those on a budget.

Lever Belts

Lever belts make use of an interlocking mechanism featuring a flippable lever to lock the belt in place.

The mechanism allows for far greater and more consistent pressure to be achieved with the belt, although it comes with the tradeoff of a higher price tag and a more complex method of adjustment in comparison to prong belts.

Specifically, lever belts are usually adjusted by unscrewing the lever mechanism from the belt itself and re-attaching it at a different point.

Lever belts are often preferred by professional weightlifters due to their more consistent pressure and greater durability.

Velcro Belts

Somewhat less common but nonetheless still available - certain forms of weightlifting belt make use of velcro padding in order to maintain pressure along the abdomen.

Rather than adjusting a lever or fitting a prong into a hole, velcro belts instead require the lifter to simply wrap the barbell around their waist as tightly as possible, the velcro automatically holding the front of the belt in place.

Although the use of velcro is not as secure or robust as prongs or levers, velcro belts are nonetheless the lightest form of weightlifting belt and are adjusted as easily as simply wrapping the belt around once more.

The velcro belt is most often encountered in less intense training sessions where heavy-duty intra-abdominal pressure is not as required - or in cases where constantly adjusting the tightness and position of the belt is needed.

What are the Advantages of Using a Deadlift Belt?

Weightlifting belts offer a surprising number of advantages beyond simply protecting the lower back.

If adjusted correctly, deadlifting with a belt can improve how much weight you can lift, improve your technique and reduce joint strain - even in cases where your form is otherwise perfect.

Acute Injury Prevention

Belts help prevent issues related to poor lower back curvature or abdominal contraction.

Hernias, sprains of the lower back muscles and even spinal disc damage are all examples of acute injuries that can be sustained when heavy deadlifts are performed with less than optimal form.

Fortunately, one of the most important benefits offered by weightlifting belts is prevention of such injuries in a twofold manner.

Not only do these belts provide a surface that the core muscles can brace against, but they also mechanically prevent the lower back from rounding - thereby acting as an additional layer of protection alongside proper conditioning and technique.

Keep in mind that deadlift belts do not prevent all forms of injuries related to heavy lifting. It is still entirely possible to tear a bicep or sprain an ankle when deadlifting with a belt, for example.

Reduced Back and Spine Strain

Apart from preventing acute injury, belts also reduce the overall strain placed on the back and the spinal column itself.

This is achieved through a combination of proper technique reinforcement, mechanical support of the trunk and better distribution of pressure throughout the abdomen.

Even in cases where the deadlift is performed with textbook-perfect form, strain from performing a repetitive movement pattern under heavy load is still an issue.

Remember to perform a proper cool-off, prioritize recovery and to use a belt if you deadlift with high volume, high load and high frequency.

Greater Strength

Weightlifting belts offer the secondary benefit of allowing for more weight to be lifted during a deadlift repetition.

Depending on the type of belt used, your own familiarity with deadlift technique and the position of the belt - as much as 20% of your 1RM can be added to your working weight.

The boosted deadlift strength seen from weightlifting belts comes as a result of the greater intra-abdominal pressure they allow for - increasing rigidity of the trunk and helping distribute force into the upper body.

Tunes Lifting Technique

Belts help lifters perfect their deadlift technique by ensuring the lower back remains flat and neutral while simultaneously providing a surface to brace the core against.

These two mechanics are vital to proper deadlift form - of which would otherwise not be possible as other cues like keeping the chest out or properly hinging at the hips rely on proper trunk form.

What are the Disadvantages of Deadlift Belts?

Although deadlifting with a belt does indeed offer a number of benefits, there are a few disadvantages you should consider prior to ordering one.

Pain and Discomfort

Because of how tightly belts can wrap around the waist, some level of discomfort and pain should be expected - especially among individuals with shorter torsos or larger bellies.

While this can be mitigated by loosening the belt slightly or selecting a custom-sized belt, powerlifters or individuals who wish to maximize the help they get from the belt may not have such options.

In more extreme cases, bruising and pinching can occur around the base of the ribcage or along any fat stores that may be present around the belly.

Can Increase Circulatory System Pressure

Lifters with a history of systemic issues relating to their blood pressure may wish to avoid using a belt, or even avoid performing exercises like the deadlift entirely.

The maximized intra-abdominal pressure created by bracing the abs against a weightlifting belt can cause a spike in diastolic blood pressure. In susceptible populations, this can lead to a number of acute health issues - some of which may be life threatening.

Speak to a medical professional prior to attempting any sort of intense exercise (belt or not) if you have a history of circulatory issues.

Can be a Crutch for Poor Form and Poor Core Bracing

Occasionally, weightlifting belts may be used to help compensate for otherwise poor form or a lack of abdominal control by the lifter. While this can indeed help prevent injury and smooth out the overall set, it is an entirely bad habit and will only hinder further progress by acting as a crutch.

This is the main reason why lifting belts are considered unsuitable for novice lifters, especially in regards to the deadlift.

Mastering proper technique unassisted (and conditioning the body to properly bracing) is essential for continued progression and better muscular development.

Factors to Consider When Deadlifting With a Belt

Like all other forms of equipment, utilizing a belt correctly requires a small amount of familiarity with its operation - as well as awareness of when to use a belt in the first place.

Belt Placement

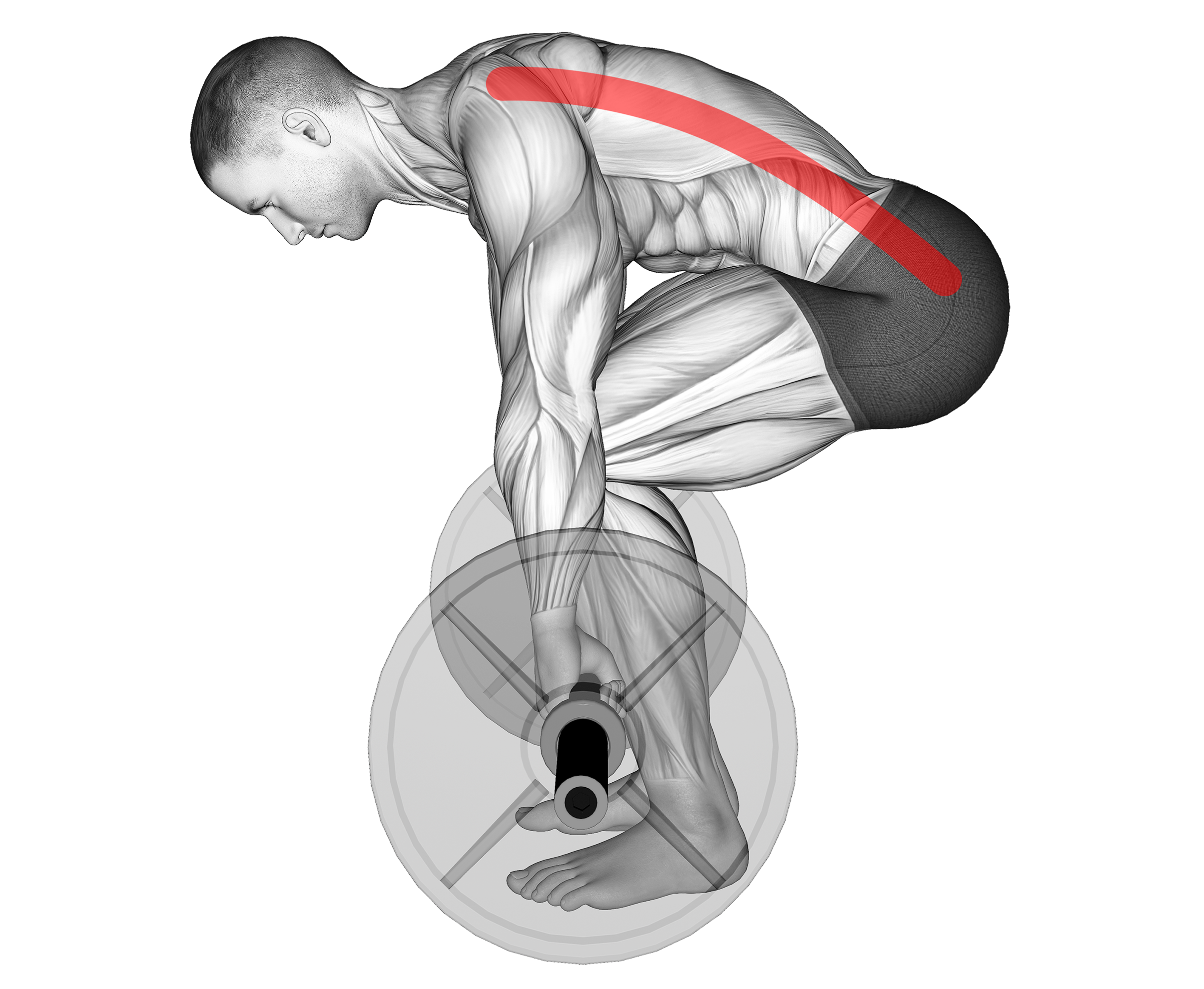

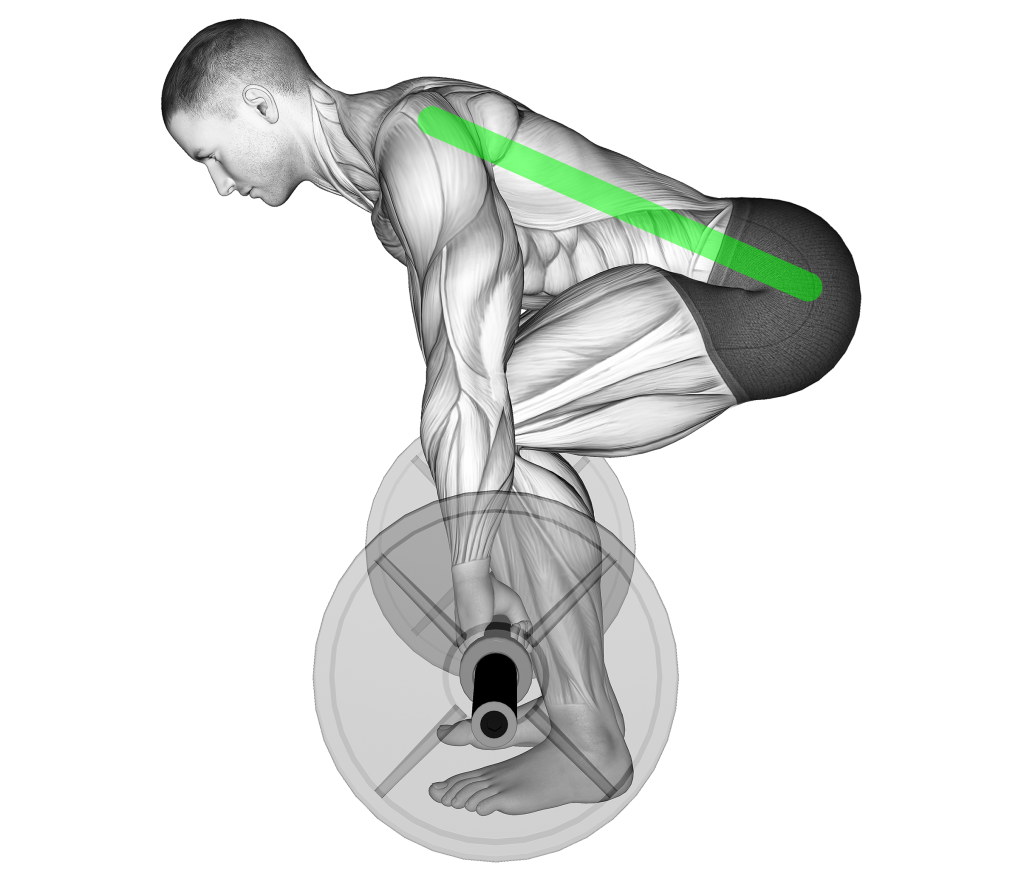

The ideal placement for a deadlift belt is around the lower section of the abdomen if pulling sumo, and slightly higher near the base of the ribcage if pulling conventional.

While this can obviously be modified to suit individual proportions and preferences, deadlift belt positioning will tend to follow this trend of placement.

The belt should be positioned so that the lower back cannot round at any point while hinging, but also be high enough that a proper brace can be maintained.

Tightness

Apart from the actual position of the belt around the trunk, the specific level to which it compresses the abdomen should also be considered.

Exercises that involve vertical pressure atop the trunk will require somewhat less tightness around the abdomen, as this will effectively prevent the lifter from inhaling correctly. However, if speaking specifically of the barbell deadlift, this is not the case at all.

Though highly individual, aim to tighten the belt as much as possible without limiting your range of motion, capacity to breathe or causing pain. Generally, deadlifts will call for the tightest belt pressure among all other compatible exercises.

Belt Dimensions

As mentioned previously, weightlifting belts come in varying widths, lengths and levels of thickness.

As you can likely guess, greater thickness equates to a more rigid and heavy belt - providing more support and a stronger scaffolding to brace against, but also potentially limiting your range of motion or sense of comfort.

Belts will range from a low 7 millimeters in thickness up to 13 millimeters, with the latter being the maximum designated thickness for most powerlifting federations.

Apart from thickness, weightlifting belt brands can also differ widely in terms of belt width.

Lifters should first try on a series of belts prior to purchasing one, as individuals with shorter abdomens may find that particularly wide belts can reach their ribcage. Likewise, those with longer trunks may find narrow belts to be insufficient for preventing lower back rounding.

A suitable belt width should ideally cover most of the belly, allowing the diaphragm to peek out over the top but still allowing the top of the hips to remain uncompressed.

Bracing Into the Belt

Apart from positioning and configuring the belt correctly, lifters should also ensure that they are actually bracing into the belt itself.

While schools of thought vary on how to properly brace the core, the general advice revolves around flexing the abdominal muscles and performing a diaphragmatic breath or “stomach” breath so the entire abdomen presses into the belt.

Now braced, ensure that the tension and abdominal contraction present around the stomach remains consistent throughout the entire set. Also ensure that you exhale at some point during each repetition, as keeping the core braced without exhaling can easily lead to syncope.

Matching the Belt With the Exercise/Intensity

As a final side note, remember that not every exercise needs a belt. In fact, using a belt outside of the right context can actually be detrimental to your training.

Performing relatively low-intensity repetitions of the deadlift should not require a belt outside of a few highly specific medical circumstances, and movements that do not involve core bracing or lower back neutrality do not need a belt whatsoever.

If performing deadlifts with a belt despite not needing one, it is likely that certain core muscles present in your back will be undertrained - leading to injury and instability in the future. Belts should be utilized in a strategic manner, reserved for near-maximal loads or circumstances where the injury risk is significant otherwise.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is it Good to Wear a Belt When Deadlifting?

Like most other forms of equipment, belts are entirely situational and their usefulness will depend on the specific context in which the deadlift is performed.

If you are warming up, a novice or do not already have core bracing down to pat - then using a belt will only hurt your training, not help it.

That being said, using a belt can indeed be quite beneficial when deadlifting. Deadlift belts protect the spine, improve strength and reduce strain on the entire trunk.

What is the Best Belt Thickness for Deadlifts?

Aim for a belt thickness that balances your individual sense of comfort with sufficient durability. Keep in mind that thicker does not always equate to better.

A 10 millimeter belt is a good starting point for most men, whereas women may benefit from 8-9 millimeter belts instead.

Do Lifting Belts Protect Your Back?

Yes - lifting belts help protect the back, especially the lower section and the underlying spinal column. This is achieved by giving the core muscles ample opportunity to contract and by mechanically preventing rounding of the lower back.

However, keep in mind that you shouldn’t entirely rely on belts to protect your back. Always follow proper form and avoid lifting more than you are able.

References

1. Fong SSM, Chung LMY, Gao Y, Lee JCW, Chang TC, Ma AWW. The influence of weightlifting belts and wrist straps on deadlift kinematics, time to complete a deadlift and rating of perceived exertion in male recreational weightlifters: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Feb 18;101(7):e28918. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028918. PMID: 35363215; PMCID: PMC9282110.

2. Miyamoto K, Iinuma N, Maeda M, et al.. Effects of abdominal belts on intra-abdominal pressure, intramuscular pressure in the erector spinae muscles and myoelectrical activities of trunk muscles. Clin Biomech 1999;14:79–87.