Belt Squat vs Back Squat: Differences Explained

Two classic lower body exercises with distinctly different purposes; the belt squat and the back squat are occasionally compared due to their similarity in movement pattern. Despite this, they could not be more different in their respective uses.

The back squat is a heavy strength-focused exercise meant for functionality, and the belt squat is a moderate-intensity movement most often performed by previously injured individuals.

Although the belt squat and back squat are both squatting movements, the back squat will load the weight atop the back, whereas the belt squat will not. This is the reason for their contrasts in utilization and muscular recruitment.

What are Belt Squats?

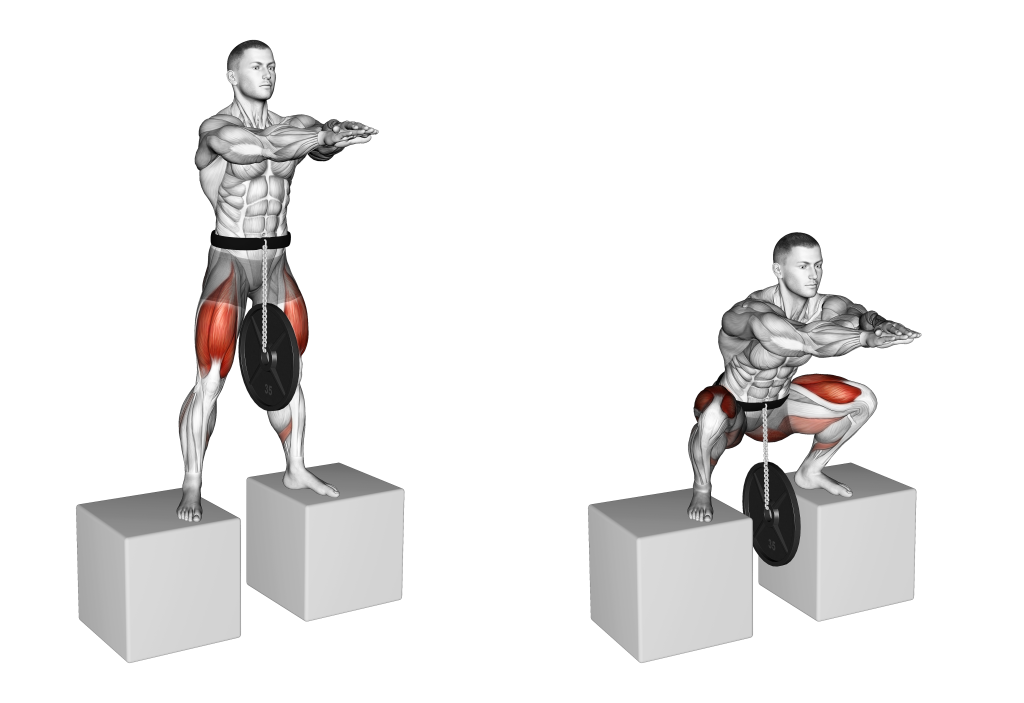

Belt squats are a compound lower body exercise performed either with the use of a belt squat machine or with a dip belt wrapped around the lifter’s waist as they stand atop an elevated platform.

Although it utilizes knee flexion and hip hinging like other squat exercises, the belt squat does not place the load atop the back, thereby reducing the risk of injury and allowing for a somewhat freer upper body stance.

Belt squats are most often performed as a back squat substitute by individuals with a history of back injuries, or as a supplementary lower body exercise.

Benefits of Belt Squats

The main benefit to the belt squat is its high capacity for loading despite a low risk of injury. This allows it to target much the same muscles as any other squat variation without the same limitations.

Safety and loading aside, the belt squat is also quite effective at focusing the lifter’s efforts on the lower body itself. While movements like the deadlift or squat will be limited by the lifter’s grip strength or core endurance, the belt squat is as pure a lower body exercise as they come.

How-to:

To perform a repetition of the belt squat, the lifter will either wrap the machine’s belt around their waist or otherwise stand atop an elevated platform with a loaded dip belt around their waist. Both forms of the belt squat are essentially the same, with the main difference being the type of equipment used.

Once an appropriate amount of weight has been selected and the exercise is ready to be performed, the lifter will contract their core, set their feet slightly wider than hip-width apart and ensure their spine is curved neutrally.

Then, the lifter will bend at the knees and push their pelvis backwards, keeping the chest upright as they do so. This may be more difficult with the dip belt variation of the exercise, and it is advised to extend the hands forwards for better balance.

Once the top of the pelvis is approximately parallel with the knees, the lifter will drive through their heels and return to the original upright position - thereby completing the repetition.

What are Back Squats?

Back squats are the quintessential lower body exercise. They are a compound free weight exercise most often performed for building strength and power throughout the lower body.

Utilizing knee flexion and hip hinging, the back squat will primarily be performed with a loaded barbell placed atop the back - hence its name. This is the main point of distinction between the back and belt squat, as the mechanics are largely the same.

The back squat is frequently used as the main exercise in lower body workouts, but may also play a secondary role to more complex or heavier movements, such as the barbell deadlift or power clean.

Benefits of Back Squats

The primary benefit of the back squat is its sheer effectiveness as a lower body training tool. When programmed appropriately, the exercise can build strength, mass and power in all the major muscle groups of the lower body - all while targeting the core, erector spinae and other stabilizer muscles as well.

In addition, squats are the most basic form of lower body exercise, replicating the natural squatting movement that we are born with. This makes them quite a functional exercise, as they develop the sort of leg strength that is applicable to a wide number of activities.

How-to:

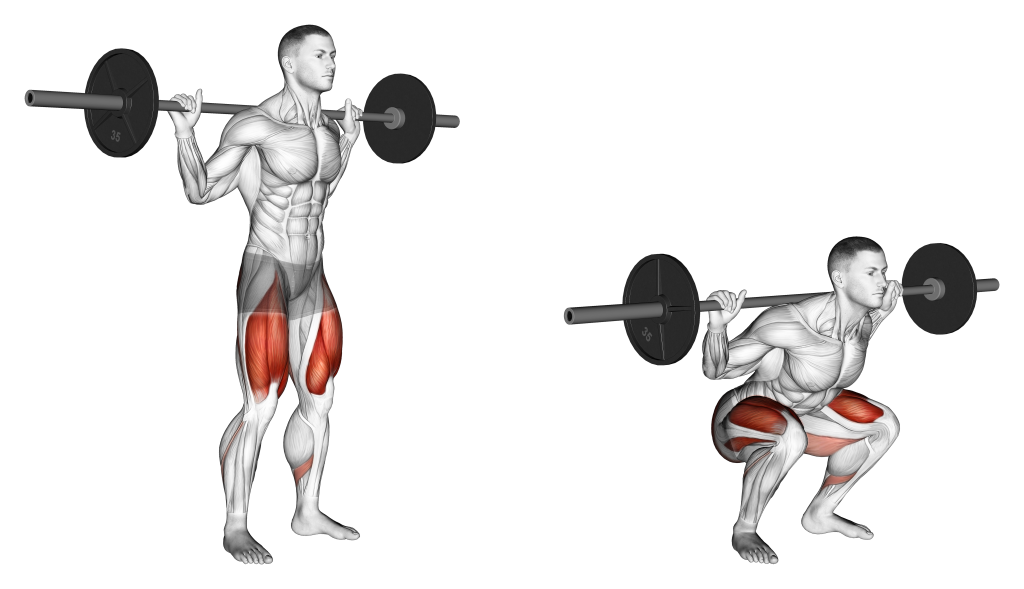

To perform a repetition of the barbell back squat, the lifter will need to unrack a loaded barbell atop their trapezius muscles, hands securing it therein.

With the bar balanced atop the back, the lifter will set their feet approximately hip-width apart, toes pointing forwards or slightly outwards. The core should remain contracted throughout the repetition, with care taken to keep the lower back in a neutral position as well.

Now in the correct stance, the lifter will bend at the knees and push their hips backwards, lowering their body until reaching at least parallel depth.

Once the proper depth has been achieved, the lifter will then push through their heels and rise back to a standing position.

The repetition is considered complete when the lifter is in an upright position once again.

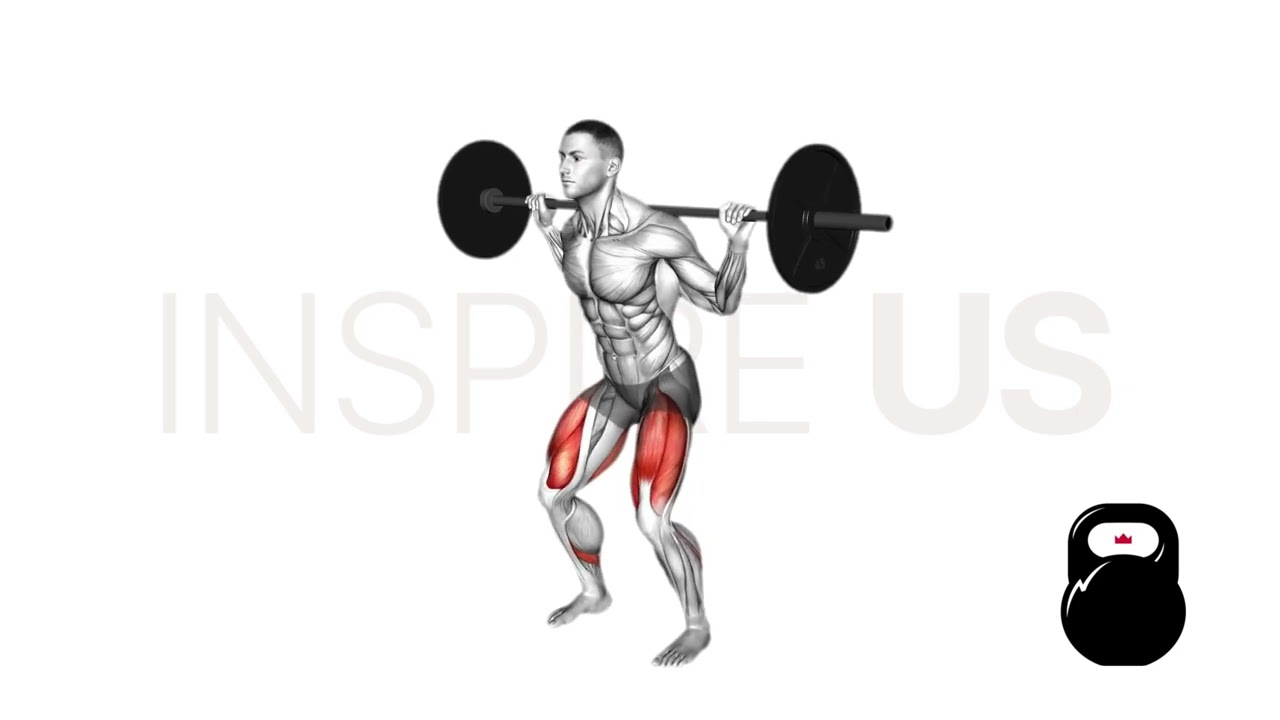

Belt Squat vs Back Squat - Muscular Emphasis and Stabilizer Muscle Recruitment

At a larger scale, the belt squat and the back squat target much the same muscle groups. These are primarily the quadriceps, glutes and hamstrings.

However, the two exercises do differ somewhat in terms of which muscles are emphasized, as well as whether other muscle groups are used in an isometric capacity.

Emphasis on Certain Muscles

Because the back squat loads the body from the top of the back, the lifter will need to recruit their posterior chain to a slightly greater degree than would be the case with the belt squat.

In comparison, the belt squat allows for a somewhat more quadriceps-dominant stance to be adopted, so long as the lifter maintains their balance correctly.

Overall however, the difference between the belt squat and back squat is negligible as far as mobilizer muscles go. Both will elicit a largely similar level of recruitment in the main muscle groups of the legs.

Stabilizer Muscle Involvement

Stabilizer muscles are simply muscle groups contracted isometrically during an exercise, meaning that they do not noticeably contract or lengthen in order to complete the exercise’s movement pattern.

In terms of comparing the belt squat and back squat, it can effectively be said that the back squat elicits far greater stabilizer muscle recruitment than the former exercise. This, like many other differences between the two, is due to the position of the weight atop the lifter’s back.

Because the barbell is atop the back, the lifter will need to utilize their erector spinae to keep the back aligned correctly as well as use their core to help stabilize the entire body.

In comparison, the belt squat utilizes these stabilizer muscles to a far lesser degree, better “isolating” the muscles of the legs.

Belt Squat vs Back Squat - Strength, Hypertrophy and Power

Because of the differences in load distribution, stabilizer muscle usage and muscular recruitment, the belt and back squat are used for distinctly different purposes.

While this is not to say that the two aren’t interchangeable in such contexts, it does mean that one may be more effective for certain types of training than the other.

Which Exercise is Better for Building Strength?

In terms of developing gross lower body strength, both exercises are comparable, but it is the back squat that wins out. This is simply because more weight can be loaded atop a barbell than can be attached to a dip belt.

Much the same answer holds true for the machine variation of the belt squat, where its machine-based nature also makes it a poor exercise for developing physical strength.

Which Exercise is Better for Building Mass?

In terms of inducing hypertrophy, the machine variation of the belt squat may be a slightly more effective choice than its free weight counterpart, or even the back squat itself. The belt squat’s capacity to isolate the lower body to a greater extent allows for fewer limiting factors to end a high-volume set prematurely.

In addition, belt squats are somewhat more effective at working the quadriceps than the more glute-focused back squat, allowing for superior hypertrophy of the main anterior leg muscles.

Which Exercise is Better for Building Power and General Athleticism?

Whether for building lower body power or as part of an athletic training program, the back squat is a better choice than the belt squat.

The back squat is superior to the belt squat in both stabilizer muscle recruitment and loading capacity. Both are vital for building muscular power and functionality - and are otherwise not as present with the belt squat.

Furthermore, because the back squat is more complex in form and demanding in coordination, it can be quite useful for developing both aspects of an athlete’s abilities. This is especially applicable for powerlifters, who practice the back squat as a competition lift in their sport.

Belt Squat vs Back Squat - Loading Capacity and Complexity

Despite featuring similar mechanics and a nearly identical stance, the belt squat and back squat differ in terms of how much weight can safely be lifted, as well as how technically complex their individual form is.

Differences in loading capacity and form complexity indirectly affect how risky an exercise is - of which will also affect whether an exercise is suitable for novices.

Capacity for Weight Loading

In terms of how much weight can be loaded on to either exercise, the back squat takes the crown over the belt squat. Such a distinction is simply a result of the sort of equipment used, and it is entirely possible for a machine belt squat to be comparable to a back squat in terms of gross weight.

However, it is important to make the distinction between weight and intensity. Because the machine belt squat is a machine-based exercise that loads around the waist, the weight of a back squat will still create a more intense exercise as a whole.

This should be kept in mind when deciding which squat variation to prescribe to a novice lifter; In such a case, it is the belt squat that is a safer choice.

Complexity of Form

While both belt and back squat feature nearly identical movement patterns, the back squat is more complex as it requires the lifter to keep a neutral spine and upright torso alongside the usual squatting mechanics.

These additional form requirements make the back squat somewhat more technical in execution than the belt squat, requiring a more advanced familiarity with exercise mechanics and greater bodily coordination.

Belt Squat vs Back Squat - Spinal Loading, Accessibility and Other Considerations

As mentioned earlier in this article, the back squat and belt squat feature different distributions of load. With differences in loading come differences in injury risk - of which are further affected by the demands of either exercise.

In addition, these distinctions also make the belt squat and back squat uniquely effective in certain niche circumstances.

Injury Risk Differences

Across the board, it can be said that the back squat is a moderately more dangerous exercise than the belt squat.

The back squat not only allows for greater amounts of weight to be lifted, but it also places the weight atop the spine in a potentially unstable manner. These aspects all add up to a greater risk of injury, especially those of the lower back.

In comparison, the main risk of injury with belt squats revolves around incorrect knee tracking - of which is considerably easier to correct than the far more complex technique of a back squat.

Accessibility of the Back Squat and Belt Squat

In terms of equipment accessibility, it is likely easier to perform a back squat than a belt squat.

Barbells and weight plates are considerably more commonplace in public gyms than belt squat machines, and free weight belt squats require the lifter to set themselves up in a suitable position with a heavy dip belt beforehand.

Furthermore, many experienced lifters may initially find the usage of a belt uncomfortable around the hips and waist, especially those that are more familiar with the barbell back squat instead.

Usage in Powerlifting Training

If you are a powerlifter or are planning to compete in powerlifting, there is no question of which squat variation to pick. The back squat takes precedence over the belt squat as it is a main competition lift.

If so desired, it is possible to use the belt squat as an off-season alternative, or as a supplementary tool - however, your main squat variation should be the back squat.

Usage for Reduced Spinal Pressure

In certain cases, a lifter may be instructed by their physician to avoid loading of the thoracic or cervical sections of the spine.

If cleared by a medical professional, the lifter may wish to substitute their standard back squat with the belt squat - effectively eliminating any pressure placed on their upper and middle spine.

Of course, avoid performing any sort of heavy exercise while injured unless previously approved by a medical professional.

If Performing Both - Which Exercise Takes Priority, Belt Squats or Back Squats?

If you’ve chosen to perform both squat variations so as to take advantage of both their benefits, it may be a better idea to perform back squats prior to belt squats. This will help mitigate the risk of fatigue-related injuries, and allow you to maximize the benefits of the back squat.

So, Which Squat is Better?

Tallying up the different benefits and characteristics of either exercise, we can come to the conclusion that neither exercise is overall "better" than the other.

If you wish to maximize weight lifted, build strength and power or achieve a more functional physique - then the back squat is better.

However, for hypertrophy, a lower risk of injury and less strain on the upper body - the belt squat is superior.

Regardless of which exercise you pick, remember to pay close attention to form and avoid lifting more than 95% of your one-rep maximum regularly.

References

1. Joseph L, Reilly J, Sweezey K, Waugh R, Carlson LA, Lawrence MA. Activity of Trunk and Lower Extremity Musculature: Comparison Between Parallel Back Squats and Belt Squats. J Hum Kinet. 2020 Mar 31;72:223-228. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2019-0126. PMID: 32269663; PMCID: PMC7126258.

2. Gulick, Dawn & Fagnani, James & Gulick, Colleen. (2015). Comparison of muscle activation of hip belt squat and barbell back squat techniques. Isokinetics and Exercise Science. 23. 101-108. 10.3233/IES-150570.