Banded Hip Thrust: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

The banded hip thrust is a glute-focused compound movement primarily involving hip extension while in a semi-lying position.

Hip thrusts, regardless of equipment used, are performed primarily as an accessory movement for improving gluteal muscle mass and strength.

Most often, the banded form of hip thrust is programmed for high volume and low resistance sets - generally somewhere between 8 and 20 repetitions per set.

Are Banded Hip Thrusts Right for You?

Banded hip thrusts are quite safe and practically zero impact - meaning that lifters of any experience level can perform them. So long as attention is paid to proper form, performing band hip thrusts can only benefit you.

However, if you have a history of lower back, glute or pelvis injuries, this exercise may lead to irritation or a recurrence of said injuries. Speak to a medical professional prior to attempting it.

How to do a Band Hip Thrust

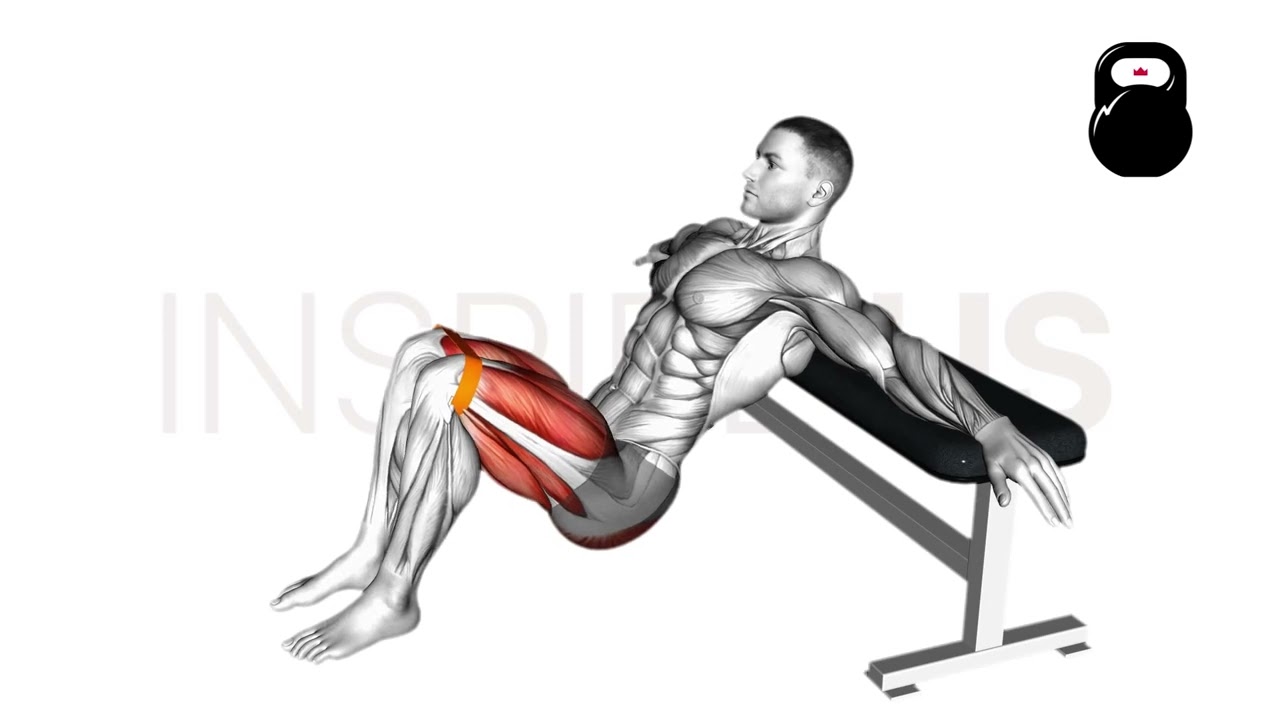

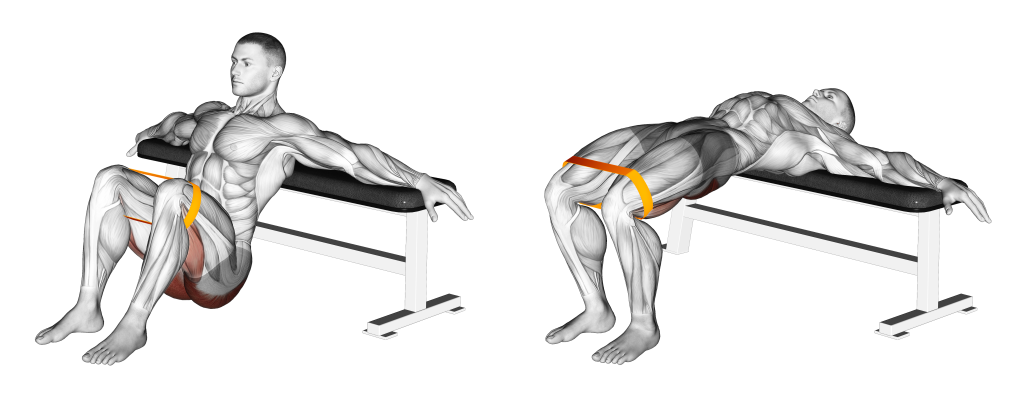

To perform a repetition of the banded hip thrust, the lifter will first place one end of a resistance band beneath their heels as they lie with their upper back atop a bench.

The knees should be bent, with the hips placed at a lower elevation as they remain in a state of flexion.

In this position, the lifter will take the opposite end of the band and loop it around the crease of their hips, ensuring it is secure before beginning the repetition.

Now positioned correctly, the lifter will contract their core and squeeze their glutes - pushing their hips upwards until it is parallel to the stomach and at a higher elevation than the knees.

The lifter then holds this position for several seconds before slowly lowering their hips back downwards - thereby completing the repetition.

For greater safety, we advise pressing the band down against the pelvis with both hands to ensure that it does not shift or slip as the set is being performed.

What Muscles do Banded Hip Thrusts Work?

Banded hip thrusts are a compound exercise with a rather narrow scope of recruitment, meaning they primarily target one muscle group while only incidentally working other muscles. This, of course, is the gluteal muscle group that makes up the buttocks.

In particular, it is the gluteus maximus section of the three gluteal muscles that is worked the hardest by banded hip thrusts. This muscle is the largest in the lower posterior chain, and primarily responsible for hip extension alongside abduction, external rotation and adduction of the femur.

In addition to these are the hamstrings and the core - both of which are targeted in only a partial range of motion or only in an isometric capacity respectively.

What are the Benefits of Doing Hip Thrusts With a Resistance Band?

Banded hip thrusts offer the following advantages over similar exercises.

Excellent for Building Glute Muscle Mass

The main benefit to doing banded hip thrusts is its capacity to induce muscular hypertrophy in the glutes - a result of its large range of motion, excellent isolation of the glutes themselves and simple mechanics.

When programmed for moderate or high volume sets, the banded hip thrust will allow for significant development of muscle mass throughout the glute muscles, especially in the gluteus medius and maximus muscles.

Reinforces Hip Extension Mechanics

The glute muscles are responsible for (among others) the mechanic of hip extension.

With the entire movement pattern of banded hip thrusts being this exact mechanic, it’s no stretch of logic to see why regularly performing the exercise will reinforce the lifter’s execution of hip extension in other activities.

Not only will the lifter be able to do so with greater force, but performing hip thrusts will also make their hip extension smoother, more stable and allow for a greater range of extension in those with poor mobility.

Low Impact and Low Injury Risk

In comparison to other glute exercises like good mornings or stiff-legged deadlifts, the banded hip thrust is quite safe and unlikely to result in strain or injury to the joints of the body.

With such a low risk of injury and a rather simplistic movement pattern, novices and recently recovered lifters will find that the banded hip thrust is ideal for getting back into the flow of training their posterior chain.

In addition, the use of bands helps avoid the usual discomfort and bruising seen when doing hip thrusts with barbells or dumbbells.

Easy to Program and Modify as Needed

The banded hip thrust is simplistic yet effective enough to be modified for a variety of different purposes.

Unilateral gluteal training can be partially achieved by performing one-legged banded hip thrusts, for example.

Likewise, simply performing the movement on the floor turns it into a banded glute bridge - and standing with one end of the band anchored behind the body turns the movement into a standing band hip thrust.

If there is a specific aspect or characteristic of the banded hip thrust that you dislike, then there is likely a variation that better fits your needs.

Carryover to Other Glute-Focused Exercises

Like other highly focused exercises, directly strengthening, mobilizing and building the glutes will create improvement in unrelated exercises and activities - especially those that primarily rely on the glutes as well.

Deadlifts, squats, leaping into the air or rising from a chair can all be made safer, easier and more effective by performing banded hip thrusts as the underlying muscle needed is subsequently stronger as well.

Common Banded Hip Thrust Mistakes

Although it is indeed true that the banded hip thrust is considered to be quite safe, avoid the following common mistakes so as to get the most out of the movement itself.

Incomplete Range of Motion

In order for muscles to develop to their fullest extent and avoid issues like instability and sticking points, it is important to train them through their full range of movement.

Performing the banded hip thrust is no different. To truly strengthen and grow the glutes, ensure the exercise begins with the hips in a state of flexion and that the body forms a relatively flat plane from knee to chest at the apex of the repetition.

An insufficient range of motion can lead to certain portions of the glutes being underdeveloped and even result in poor mobility if done for extended periods.

Excessively Fast Tempo

Performing banded hip thrusts too rapidly can cause a number of different issues ranging from poor glute development to injury of the lower spine.

For a safer and more effective workout, it is best to stretch out each half of the repetition to at least one second, being careful to properly engage the glutes and achieve a full range of motion as you do so.

Anterior Pelvic Tilt

One mistake that can lead to strain on the lower back is tilting the top of the pelvis towards the anterior side of the body. This is often from excessive glute contraction at the start of the repetition, and can appear as if the lower back is arching with the glutes being stuck outwards.

Although the glutes do indeed need to be contracted in order to properly perform the exercise, it is best to first engage the core and ensure the lower back is only in a neutral curvature prior to beginning the repetition.

Performing the banded hip thrust with excessive anterior pelvic tilt can lead to strain of the lower back, poor repetition tempo and even poor range of motion if particularly severe.

Arching the Lower Back or Hyperextending Hips

Much like with anterior pelvic tilt, avoid arching the lower back or pushing the hips beyond parallel to the waist. Both are mistakes distinct to anterior pelvic tilt, as they can still occur regardless of the rotation of the pelvis itself.

Arching of the lower back is often a sign that the feet are positioned too close or too far from the upper back - or that poor core contraction is occurring.

To correct this particular issue, aim to brace the core and ensure that the lower back is in a flat line at the start of the repetition.

Likewise, extending the hips too high into the air can also strain the lower back as it creates a similar curvature to having an arch.

However, fixing this problem is less about properly contracting the core and more about knowing when to terminate the apex of the movement.

Perform hip thrusts next to a mirror and aim to stop when the hips are parallel to the waist or knees - familiarize yourself with this position so you can still achieve it, even without the use of a mirror.

Driving Through Heels

The banded hip thrust is meant to drive all of its force from the gluteal muscles themselves - meaning that if driving through the heels, it is likely that the quadriceps or calves are being recruited, rather than the glutes.

While the heels should indeed be flat on the ground to support the rest of the body, no force should be translated through them whatsoever.

If you’re having difficulty completing a banded hip thrust repetition without driving through the heels, try drawing the legs closer to the torso or using a wider stance for greater stability.

Alternatives to the Banded Hip Thrust

Whether you’re looking for a more intense exercise or something more dynamic, the three following banded hip thrust alternatives are worth a look.

Barbell Hip Thrust

The barbell hip thrust is practically identical to the banded variation, only with a loaded barbell balanced atop the crease of the hips.

Picking a barbell over a resistance band allows for significantly greater loading to be achieved and a consistent amount of resistance throughout the entire range of motion. However, it can also greatly increase discomfort and potentially lead to injury as an inherent risk related to heavier loading.

Use the barbell hip thrust if you don’t have a sufficiently thick band available, or wish to up the intensity of your hip thrusts in a more convenient manner.

Glute Bridges

Glute bridges are simply hip thrusts performed with the upper back lying on the ground.

In comparison to hip thrusts, they feature a somewhat smaller range of motion, reduced glute activation and an even lesser risk of injury.

Select glute bridges as a banded hip thrust substitute if no resistance band or bench is available - or if you wish to further simplify the exercise.

Banded Side Steps

Banded side steps are a highly dynamic compound movement involving the lifter wrapping a resistance band around their shins and stepping one leg out to the side while in a half squat position.

This engages the hamstrings, quadriceps and calves alongside the glutes, and is excellent for improving leg abduction function while simultaneously building muscle mass and strength.

As a banded hip thrust substitute, the banded side step is most effective for athletes or those that find the isolating nature of the hip thrust to be too time-consuming or limiting in the scope of their posterior chain training.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Which is Better, Banded Hip Thrusts or Barbell Hip Thrusts?

Neither variation of hip thrust is necessarily better than the other.

Barbell hip thrusts allow for heavier increments of weight to be added and a consistent amount of resistance applied throughout the range of motion. Likewise, banded hip thrusts are somewhat safer, lower impact and more comfortable.

Is it Okay to Do Banded Hip Thrusts Every Day?

Outside of low intensity exercises, it is best to avoid performing any form of resistance training multiple consecutive days in a row. Doing so leaves the body no time to recover, reading to overtraining, injuries and generally poor development.

Aim to perform banded hip thrusts at most 3-4 times a week with at least one day of rest between each workout.

What’s Better, Squats or Hip Thrusts?

Squats are a compound exercise targeting the quadriceps, hamstrings and glutes to significant intensity.

In comparison, hip thrusts are considered a compound exercise that primarily works the gluteal muscles alone. Although they reportedly do activate the glutes to a similar degree, they nonetheless barely recruit the hamstrings or other muscles.

As you can guess from these descriptions alone, comparing squats and hip thrusts isn’t quite practical as they serve drastically different purposes. For the best results, perform both squats and hip thrusts. This will help maximize lower posterior chain muscular development.

References

1. Neto WK, Vieira TL, Gama EF. Barbell Hip Thrust, Muscular Activation and Performance: A Systematic Review. J Sports Sci Med. 2019 Jun 1;18(2):198-206. PMID: 31191088; PMCID: PMC6544005.

2. González-García, Jaime, Esther Morencos, Carlos Balsalobre-Fernández, Ángel Cuéllar-Rayo, and Blanca Romero-Moraleda. 2019. "Effects of 7-Week Hip Thrust Versus Back Squat Resistance Training on Performance in Adolescent Female Soccer Players" Sports 7, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7040080

3. Plotkin, Daniel L et al. “Hip thrust and back squat training elicit similar gluteus muscle hypertrophy and transfer similarly to the deadlift.” bioRxiv : the preprint server for biology 2023.06.21.545949. 5 Jul. 2023, doi:10.1101/2023.06.21.545949. Preprint.