At What Weight Should I Use a Belt For Deadlifts?

Although it will depend on each individual case, lifters will want to make use of a belt only when they are near the upper levels of their capabilities.

Depending on factors like fatigue, experience and injury risk, this can be as low as 70% of your one-rep maximum.

Why do People Wear Lifting Belts for the Deadlift?

Weightlifting belts are a form of assistive equipment meant to both protect the lifter from injury and improve their performance in certain respects.

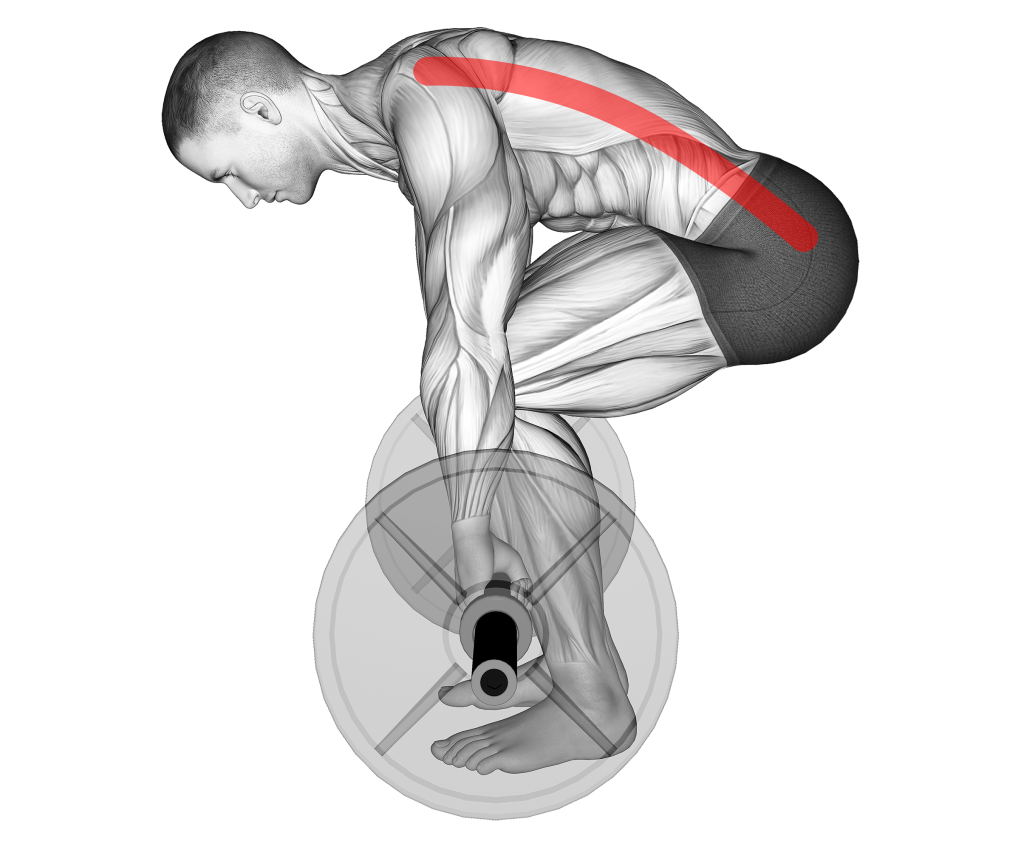

In actual practice, a deadlifter may wear a belt so as to prevent their lower back from rounding and to aid in maintaining intra-abdominal pressure by bracing the core against the tough material of the belt.

The Benefits of Using a Belt for Deadlifts

Belts mechanically prevent the lower back from curving in a way that can injure the spine or lower back muscles.

This is an especially common issue with deadlifts, where poor technique, weak core muscles or very heavy loads can cause such a breakdown in form.

Apart from protecting the lower back in this manner, belts also help translate force through the trunk - as well as allow for more efficient contraction of the core musculature.

These two benefits combine to allow the lifter a higher maximal load and overall better strength output during a deadlift.

Things You’ll Need Before Using a Belt

Prior to locking a belt around your waist, you’ll first need to have a solid grasp of proper deadlift technique - and understand how to actually brace into a belt.

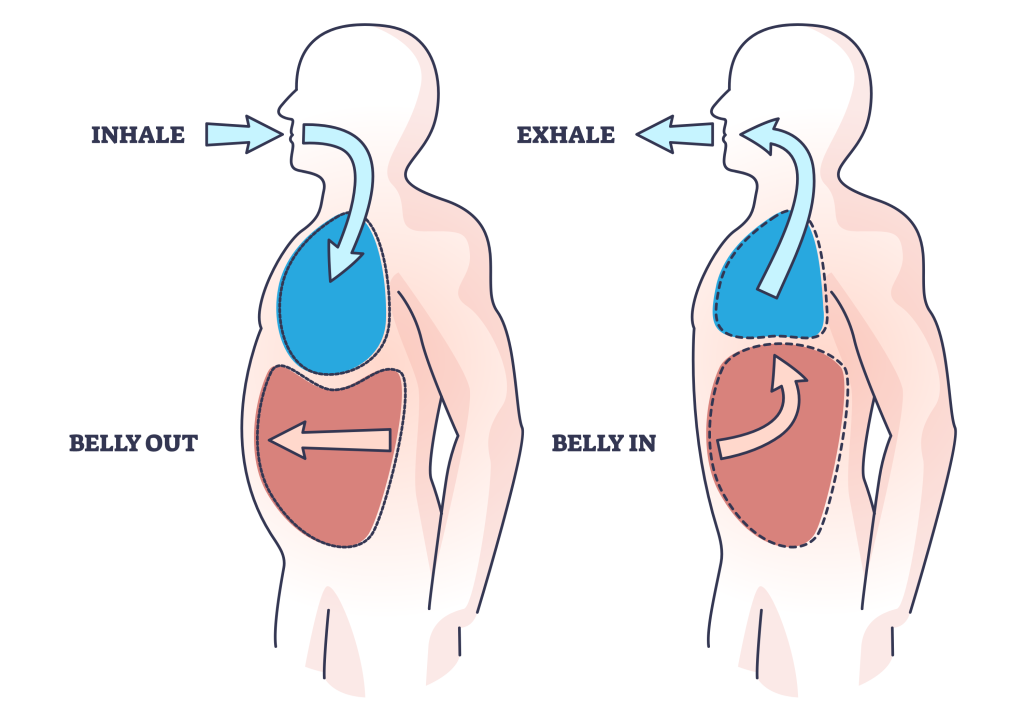

To do so, contract the abdominal muscles and perform a diaphragmatic breath, pressing the core into the belt from all sides of the abdomen.

Remember that belts are a form of assistive equipment and shouldn’t be used as a crutch for poor deadlift technique.

Belt Usage by One-Rep Max Percentage

A “one-rep max” is simply the most amount of weight a lifter can move at the absolute limit of their physical capabilities. One-rep maxes are tested and calculated in order to provide a concrete upper limit to the working weight of a lifter’s program.

Use Our Calculator to Determine Your One-Rep Max

When the question of when to use a belt for deadlifts arises, basing the answer off a specific percentage of this one-rep maximum is the most empirical way of going about things - but may not be the most personalized or safe.

Some debate lies as to what specific percentage is the exact cut-off for using a belt, as using a belt at submaximal effort loads comes with a host of disadvantages that will be discussed later in this article.

However, the majority of publications seem to agree that a range between 60-80% of a lifter’s one-rep max is a good place to use a belt.

Of course, stronger lifters, women or the previously injured should tend more towards the lower percentage out of precaution.

Picking 1RM Percentage for Belts by Experience

Strength development is rarely linear, as is the conditioning of the body outside of a purely muscular perspective.

Joints, the CNS and even the circulatory system adapt to the rigors of deadlifts at a rate somewhat slower than is seen with skeletal muscle.

As such, what may be considered a heavy lift for an intermediate lifter could potentially lead to serious injury in a novice, even if the novice is technically strong enough to lift it.

Advancing Levels of Experience

Generally, the more advanced a weightlifter is, the sooner they will want to use a belt based on a percentage of their one-rep max.

Those at the advanced or elite category can regularly be pulling over 400 pounds as their working weight - of which can easily lead to damage of connective tissue out of pure strain, even with decent form.

As such, making use of a belt at 60-70% of their one-rep max is a good precaution.

Belt Use by Novices and Intermediates (0 to Approx. 5 Years of Training)

On the opposite side, novices should avoid using a belt as it will interfere with the process of learning proper unassisted deadlift technique, and lead to poor development of certain stabilizer muscle groups.

Likewise, intermediates or those just on the precipice of being in the advanced category will likely see the best development when using belts only sparingly. Somewhere between 75-85% of their one-rep max is ideal.

Considerations for Fatigue, Gender and Strength Boosted by the Belt Itself

There are several disadvantages to basing one’s belt usage off a hard percentage of their one-rep max.

Fatigue

The most widely-reaching of these disadvantages concerns fatigue, where exercises performed prior to the deadlift, poor sleep or poor diet can all lead to a reduction in actual strength output.

What may normally be a set of 70% of a 1RM can easily become a maximal effort set when fatigued.

Of course, with a loss in actual strength comes a greater risk of form breakdown and injury - all while a belt is left unused as the lifter intends to only wear one above 80% of their 1RM, for example.

Although the percentage rule for belt usage does provide a hard number to follow, remember to also consider your current rate of perceived exertion (RPE), rather than basing the decision to go beltless entirely off said number.

Factoring in Gender and Strength Output

Although still being researched in academia, evidence points to biologically female lifters having a somewhat smaller muscle mass to strength output ratio than men - with some studies citing as much as a 55% disparity in upper body strength.

Depending on the specific study, this reason can range from the fact that men simply have greater lean mass to more individual factors like motor unit efficiency, sociological conditioning or the specific type of muscle fibers present in either gender.

Regardless of the actual reason, this smaller LBM-strength ratio means that women (like elite male lifters) should also tend towards the lower range of 1RM percentage when deciding to use a belt.

Going as low as 60-70% is perfectly suitable for intermediate or advanced female weightlifters.

Remember, Belts Boost Maximal Load

One mistake that you may make when calculating whether to use a belt is failing to account for the strength increase of a belt.

Expect that the belt will add as much as 20% to your one-rep max and take advantage accordingly.

This should also factor into your gross one-rep max number.

If performed without a belt, a 60% set may actually be easier than you thought. Depending on the sort of training being performed, this can be detrimental and lead to poorer development.

Belt Usage by Perceived Exertion

Perceived exertion is simply an attempt by scientists to create a scale with which to standardize physical exertion during exercise.

This is otherwise known as the rate of perceived exertion scale, and will vary between individuals, their tolerances and several dozen other factors that can affect physiological energy levels.

Deciding on when to use a belt can also be based entirely off your own sense of exertion at a certain deadlift load.

Rather than going by tonnage or how much weight is being lifted, deciding whether to use a belt can instead be a case-by-case situation where you assess whether you need the extra support and safety of a belt during a workout session.

Of course, like any other school of thought, there are disadvantages to this approach - of which may make it less suitable for novices or those with particularly extreme tolerances to physical discomfort at both ends of the spectrum.

Gauging RPE

The original rate of perceived exertion scale begins at a 1, of which is considered to be essentially any activity other than being asleep.

The scale steadily ramps up in terms of physical exertion, finally ending at 10 where maximal physical exertion is reached - of which is generally characterized as a highly elevated heart rate, being out of breath, unable to maintain conversation and muscles being unable to exert a consistent amount of force for more than a few seconds.

For the deadlift, a 10 on the RPE scale would likely be either a one-repetition max or a very high volume set of a moderate load.

This scale will vary - as mentioned - between individuals and specific contexts, even on a per-exercise basis itself.

Factors like sleep, age, carbohydrate intake and recovery time between sets are the most relevant of these aspects, but even individual psychology and workout environment temperature can affect a lifter’s perception of exertion as well.

Generally, lifters should seek to use a belt between the ranges of 8 (rapidly fatiguing) to 10 (impossible to sustain).

The Disadvantages of Going by Exertion

Deciding to use a belt based on exertion is limited by the lifter’s own tolerance towards physical discomfort.

Those with very low discomfort may feel as if they are near maximum effort and wear a belt too early, resulting in poor technique and reduced muscular development.

Likewise, those with a high tolerance to discomfort may forego using a belt, even when it would be safer and more advantageous to do so.

This is why it is not recommended for newer lifters or those with extreme exertion tolerances to go by RPE, as they cannot accurately gauge the right time to use a belt for deadlifts. If you are among these populations, seek the advice of a coach or base your decision off a 1RM percentage.

When Should You Not Use a Weightlifting Belt for Deadlifts?

Outside of knowing when to specifically deadlift with a belt, it’s also vital to know when not to use a belt so as to prevent poor technique habits, injuries or poor muscular development.

Those With Injuries and Conditions

Lifters with a history of hernias, diaphragm issues and individuals with medical conditions related to the circulatory system should all avoid using a weightlifting belt - or even avoid performing deadlifts entirely.

The use of a weightlifting belt greatly increases the intra-abdominal pressure during a deadlift, leading to greater outward pressure from within the abdomen.

This not only translates to a greater hernia risk if the belt is excessively tight, but also skyrockets blood pressure temporarily. Speak to a medical professional prior to performing deadlifts, belt or not.

Novices or Returning Lifters

Both novices and lifters just returning from an extended period off should avoid using belts.

In both cases, the lifter’s conscious technique and their muscles are unoptimized and relying on a belt too early in their training can result in poor technique habits and delayed muscular development.

If You Are: Warming Up, On a Deload Cycle, Practicing Technique or Performing Certain Odd Lifts

Apart from sets of sub-maximal load, other situations involving deadlifts are also impacted by the use of a belt.

Warm-ups, cool-offs or refining your deadlift technique all require that a belt not be used in order for their respective goals to be achieved.

Using a belt while warming up can result in the core muscles remaining poorly prepared, whereas the low intensity nature of cooling off does not necessitate the support or assistance of a belt whatsoever.

Likewise, refining your deadlift technique is directly prevented with the use of a belt as it prevents you from properly learning how to brace and maintain lower back neutrality.

Finally, performing certain variations of the deadlift or similar “odd lifts” may also be negatively affected by the rigidity of a belt. Particularly high deficit deadlifts, unilateral suitcase deadlifts or Zercher deadlifts all require either an adjustment in belt tightness or no belt at all.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How High Do You Wear a Weight Belt?

A weight belt should be high enough around the abdomen to brace the upper abdominals against, but not so high that it is directly compressing the ribs.

This will vary between different belt widths and individual trunk proportions, but the general idea is to cover the majority of the stomach without the belt touching either the top of the hips or the mid-diaphragm.

How Tight Should a Weight Belt Be?

As tight as possible without preventing inhalation or causing severe discomfort. Generally, the more curvature of the lower back or waist is needed, the looser the belt should be.

Avoid tightening the belt so much that it restricts breathing or causes bruising, as this defeats the purpose of the belt and can actually create a greater injury risk in certain situations.

How Do I Know if my Lifting Belt is Too Small?

If the belt covers less than half of your abdomen, then it is likely too narrow for your particular frame. A weightlifting belt that is too small may be less effective at improving intra-abdominal pressure, and may not provide as much support to the lower back as a properly fitted one.

References

1. Finnie SB, Wheeldon TJ, Hensrud DD, Dahm DL, Smith J. Weight lifting belt use patterns among a population of health club members. J Strength Cond Res. 2003 Aug;17(3):498-502. doi: 10.1519/1533-4287(2003)017<0498:wlbupa>2.0.co;2. PMID: 12930176.

2. Fong SSM, Chung LMY, Gao Y, Lee JCW, Chang TC, Ma AWW. The influence of weightlifting belts and wrist straps on deadlift kinematics, time to complete a deadlift and rating of perceived exertion in male recreational weightlifters: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Feb 18;101(7):e28918. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028918. PMID: 35363215; PMCID: PMC9282110.