Assisted Dip: Muscles Worked and More

The machine assisted dip is an exercise used either as a direct bodyweight dip substitute in populations still building a baseline of strength in their upper body - or as a finishing compound exercise by more advanced athletes.

Regardless of purpose, the assisted dip is well-established as a highly effective push exercise meant to build strength, stability and mass in the chest, shoulders and in the triceps brachii.

What are Assisted Dips?

Assisted dips are a machine-based compound upper body exercise primarily involving biomechanical action of the elbows, scapula and shoulders.

The movement is essentially a conventional parallel bar dip performed with the assistance of counter-resistance beneath the body, reducing how much actual weight is being lifted by the upper body’s muscles.

Most often, assisted dips are done in cases where the lifter cannot actually complete a full set of conventional bodyweight dips.

However, in certain forms of advanced programming, the assisted dip is also used as a secondary compound movement where conventional dips cannot be performed to the same exhaustive capacity.

How to Use an Assisted Dip Machine

To perform an assisted dip, the lifter will begin by first adjusting the resistance to an amount appropriate to their current level of strength.

Though not quite exact, one can assume that however much weight they select as resistance is subtracted from their total bodyweight. A 180 pound individual using 50 pounds of resistance will essentially be performing dips with only 130 pounds of weight.

Complete novices to dips can go as far as setting the resistance to approximately half their bodyweight, if not somewhat more.

Once the resistance has been appropriately adjusted, the lifter kneels atop the padded platform, bracing their hands against the parallel bars with the elbows at full extension. The scapula should be neutral with the shoulders externally rotated and the chest as upright as possible.

From this stance, the lifter then bends at the elbows and slowly lowers themselves downwards, pad assisting by slowing their descent and applying force counter to gravity.

When low enough to create a 90 degree angle with the elbows, the lifter then drives through their palms and squeezes their chest - pushing themselves back upwards into their original position.

With the elbows fully extended once more, the repetition is considered to be complete.

Sets and Reps Recommendation:

Whether as a secondary compound movement or as an introduction to unassisted dips, a moderate level of weight and volume should be achieved.

Too much volume can lead to joint strain and poor progress, whereas too much weight will limit volume and potentially risk acute injury.

3-4 sets of 8-12 repetitions should suffice for both hypertrophy and strength development.

What Muscles do Assisted Dips Work?

In order to identify which specific muscles receive the most benefit from assisted dips, they must be divided according to the role in which they play.

Dynamic contraction marks a muscle as a primary or secondary “mover”, whereas static contraction marks a muscle as a “stabilizer” muscle.

Primary and Secondary Mover Muscles

In terms of primary mover muscles, the pectoral muscles of the chest and the triceps brachii of the upper arms are worked to the greatest extent during assisted dips.

The pectoral muscles contract to adduct and rotate the arms, whereas the triceps brachii primarily act to extend the elbow during the latter phase of the repetition.

Further supporting these muscles are the anterior deltoid heads, acting as secondary movers as they aid in humeral flexion near the apex of the movement.

Stabilizer Muscles

Apart from the aforementioned mover muscles, assisted dips will also isometrically contract quite a few muscle groups for stability.

The most notable among these are the remaining two heads of the deltoids, as well as the entirety of the core muscles. Both of these muscle groups stabilize the trunk throughout the entire range of motion.

In addition are the trapezius and glutes, of which play a significantly smaller but nonetheless still static role through stabilization of the scapula and legs.

Common Assisted Dip Mistakes to Avoid

Despite their accessibility and relative safety, assisted dips are commonly performed with several mistakes that make them a less effective exercise as a whole. These mistakes must be corrected in order to maximize development and reduce any risk of injury present.

Poor Range of Motion

As a rule, each repetition of assisted dip must begin and end with the arms straightened beneath the body.

The deepest portion of the movement should also involve the forearms set at a 90 degree angle to the elbows, ensuring they are not strained but also maximizing the length of the pectoral muscles.

Failing to complete a full range of motion can reduce the involvement of the chest and shoulder muscles, leading to poor development and potential issues relating to technique and mobility.

Internally Rotating Shoulders

In order to reduce strain within the shoulder joint itself, lifters should avoid hunching their shoulders or otherwise rotating them inwards during assisted dips.

A good cue to avoid this particular mistake is to imagine “opening up” the chest, beginning with the shoulders over the upper arms at the top of the movement. Keeping the shoulder blades neutral can also aid with preventing internal shoulder rotation, as well as avoiding parallel bars that are set too close together.

Flaring Elbows

To further reduce strain and injury risk relating to the elbows, lifters should aim to keep their elbows pointing backwards - avoiding an immediate lateral angle as well as they can manage.

Flaring the elbows to the sides will increase internal strain of the joint while in a highly disadvantageous position, creating the perfect environment for an injury.

In most cases, flaring elbows during a set of dips is caused by an excessively forward lean to the torso, causing the elbows to compensate for the lack of shoulder rotation. Other causes can relate to hand orientation or positioning, as well as an excessively vertical descent.

Dipping Too Low

In order to avoid straining the shoulder and elbow joints, lifters should strive to avoid dipping too far downwards at the apex of the repetition. If the elbows are bent at a 90 degree angle, a full range of motion has been achieved.

Dipping too far will not only increase the risk of sustaining an injury to the shoulder joints, but may also reduce tension on the chest as the body’s weight shifts to the arms and shoulders.

Lower Back Hyperflexion or Extension

For a more stable and efficient movement pattern, the lower back must remain neutral, the entire body forming a relatively straight (but angled) line from knees to head.

Arching the back into extension can reduce the involvement of stabilizer muscles and lead to an excessively vertical torso, whereas using too much flexion can lean the upper body too far forwards and similarly reduce posterior trunk stabilizer involvement.

Variations and Alternatives to the Assisted Dip

Whether you’ve graduated out of assisted dips or simply can’t find a suitable machine, the following alternatives are worth a look.

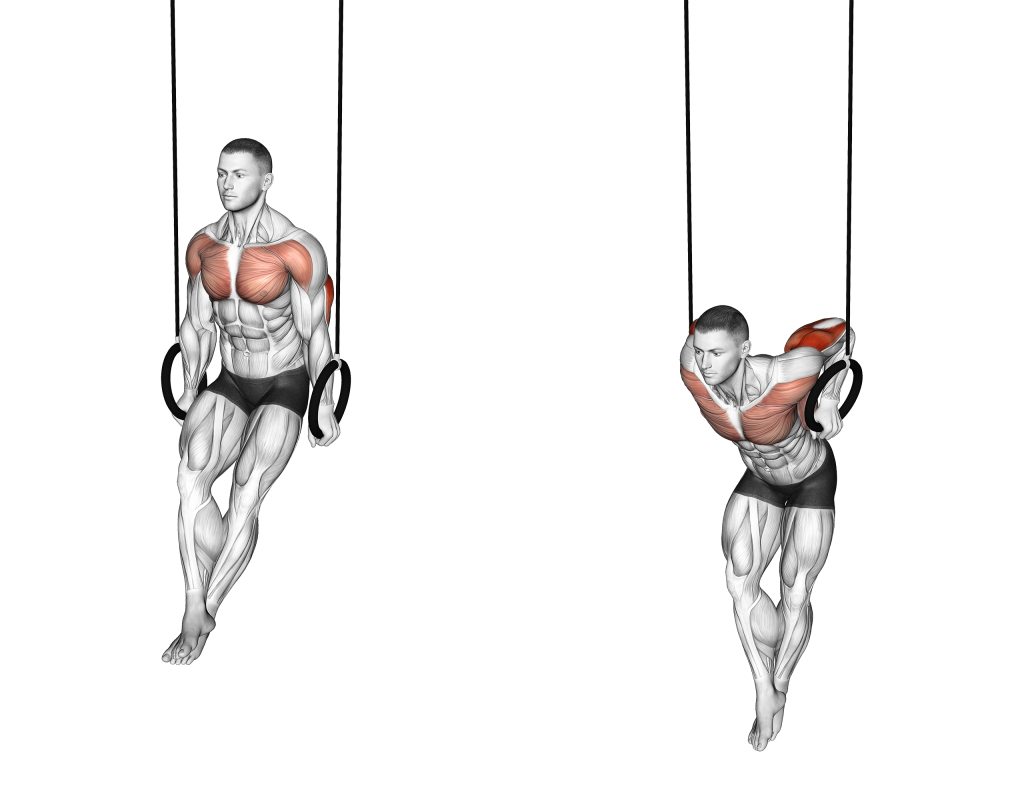

Ring Dips

Ring dips are an unassisted variation of bodyweight dip involving the use of two gymnastic rings, rather than a set of parallel bars.

Performing the movement with such equipment allows for a freer movement pattern and reduced strain on the elbows at the cost of greater shoulder exertion and core contraction.

Use ring dips as a progression exercise from assisted dips if you’re a calisthenics athlete, parkour artist or gymnast.

Resistance Band Assisted Dips

Band assisted dips simply refer to a set of assisted dip variations involving bands wrapped beneath certain parts of the body to reduce total load on the muscles.

Although far less adjustable or convenient than machine assisted dips, calisthenics athletes without access to a gym will find resistance bands comparatively more convenient and affordable.

Apart from acting in a similar capacity to machine assisted dips, the band assisted variant can also be used for correcting weaknesses found only during the bottom half of the movement pattern.

Chair Dips

Chair dips are a variation of bodyweight dip performed for greater emphasis on the triceps brachii, reducing focus on the shoulders and chest in comparison.

Like with assisted dips, a large portion of the body’s weight is distributed away from the working muscles - in this case due to the lower body resting atop the floor.

Chair dips may be used alongside assisted dips for greater triceps training volume or as a less-than-ideal substitute in cases where no dip assistance machine is present.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are Assisted Dips Good for?

Assisted dips are excellent for building up the necessary strength and skill to perform regular bodyweight dips. They are also occasionally used for maximizing strength and hypertrophic development in the chest, shoulders and triceps muscles.

Are Dips Good for Burning Belly Fat?

Not at all. Dips are primarily an anaerobic exercise meant to target the muscles of the arms, chest and shoulders.

In order to burn belly fat, a sufficient number of calories must be burned to reduce overall body fat percentage.

Although dips do indeed burn a few calories over several sets, they are largely inefficient for expending calories and have nothing to do with the abdominal area outside of isometric contraction.

What Happens if I Do Dips Every Day?

Performing heavy compound movements like dips on a daily basis can lead to chronic overuse injuries, especially of the shoulder and elbow joints.

As a general rule, it is best to avoid performing any sort of resistance exercise repeatedly every single day. Aim to keep at least 24 hours of rest between training sessions targeting the same muscle groups.

References

1. Haycraft, Jade & Robertson, Samuel. (2014). The effect of concurrent aerobic training and maximal strength, power and swim-specific dry-land training protocols on swimming performance: a review. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning.

2. McKenzie, Alec K. BClinSci; Crowley-McHattan, Zachary J. PhD; Meir, Rudi PhD, CSCS; Whitting, John W. PhD; Volschenk, Wynand BA (HMS Hons) Sports Science, CSCS. Glenohumeral Extension and the Dip: Considerations for the Strength and Conditioning Professional. Strength and Conditioning Journal 43(1):p 93-100, February 2021. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000579